Strategy is not about celebrating the past; it is not about celebrating the present; it is only about leadership in the future. Even though an organisation is a leader today, it cannot assume it will continue to be so tomorrow. Earning that leadership is what strategy is all about. But what we also know is that industry changes in the future. Therefore, if you want to be a leader in the future, you have to adapt to change. And another word for adapting to change is innovation. Therefore, I say strategy is innovation. If you are not doing innovation in your company, you are not doing strategy; you are doing something else.

Whenever I work with Indian companies, I ask them a very simple question: Think about all the projects that you are executing today. How many of them will make you a leader in the future? I can frame this question in another way: Think about all the projects that you are executing today and put them into three boxes. Box 1 is about managing the present; that is, improving the performance of your current businesses on an as is basis. Box 2 is about selectively forgetting the past. Box 3 is about creating the future. How many of the projects you are executing today are in Box 1, Box 2 and Box 3?

Strategy is always about how we create a future while managing the present. How do you shape the evolution of an organisation for the year 2025 when you are quietly executing projects in the year 2016? The reason this is a challenge is because the thinking process and execution methodologies you need in Box 1, which is all about efficiency, are fundamentally different from the thinking process and the execution methodologies you need in Box 2 and Box 3, which are all about innovation.

You better have Box 1 projects in 2016. But at the same time, you better have Box 2 and Box 3 projects targeted at the future as well. Both sets of projects require different capabilities, metrics, processes and people. This is the central strategic challenge. The solution to this challenge is simple, but not always easy to execute. The answer in fact is common sense: the future is now. It is never about what we have to do in the future. The reason this is so hard to do is that today as an organisation, I have two jobs to do. One job is in Box 1, and another job is in Box 2 and Box 3–and that job is inventing the future. Yet, there are inherent conflicts, paradoxes and tensions between the two. This is the central leadership challenge.

The fundamental difference between Box 1 projects on the one hand, and Box 2 and Box 3 projects on the other, is that competition for the present projects (Box 1 projects) is always in response to what I call clear signals and linear changes in the industry. The organisational response to these signals and changes would be incremental improvements in its current business model. Call them Six Sigma quality, continuous process improvement, total quality management or operational excellence, these are all important ideas but they are Box 1 ideas. Competition for future projects (Box 2/ Box 3 projects) is always in response to what I call weak signals and nonlinear changes in your industry. The organisational response to non-linear changes in the industry will be breakthrough innovation, fundamental innovation, exponential innovation or non-linear innovation. If we look at the last two decades, I would say the Internet was such a non-linear change. Concepts such as eBay, Amazon.com, Google and Flipkart, to name a few, would not have happened without a disruption called the Internet.

Non-linear Change and the Indian Market

In the context of Indian companies looking at say, the next two decades, what would be the non-linear changes that could create tremendous opportunities for non-linear innovation? Certainly, technologies will continue to transform every industry. But technology is not the only source of non-linear change. Nonlinear change will also be driven by huge customer discontinuities. Customers of the future could be fundamentally different from the customers of today. If they are fundamentally different, they will also demand Box 3 innovation. An example of a customer discontinuity that is impacting just about every population in the world can be seen in emerging markets – countries like India and China. If you are an American company, you cannot take the business models you created for the American consumer in Box 1 and simply send those business models to India and China and hope to capture their mass markets. Why? Because emerging markets represent a huge customer discontinuity. Customers in emerging markets are fundamentally different from customers in developed markets, and because they are fundamentally different, they will demand Box 3 innovation. How do we know this is true? Take for instance a simple statistic like per capita income. Per capita income in the US is US $50,000. Per capita income in India is US $1,500. What that tells me is that there is no business model that you, as an American company, have created in Box 1 for middle-class America, that you can simply send to India with the hope of capturing middle-class India where the mass market is. You have to engage in non-linear innovation.

In the context of Indian companies looking at say, the next two decades, what would be the non-linear changes that could create tremendous opportunities for nonlinear innovation? Certainly, technologies will continue to transform every industry. But technology is not the only source of non-linear change. Non-linear change will also be driven by huge customer discontinuities. Customers of the future could be fundamentally different from the customers of today.

General Electric’s healthcare business is a good example of using a Box 3 innovation approach to unlock tremendous value in India. GE Healthcare’s portable electrocardiogram (ECG) machine was innovated for the American consumer. It is an extraordinarily powerful machine that has saved millions of American lives. It costs about US $20,000. GE sells this machine in India to the top 10% of the economic pyramid. After all, there are rich people in poor countries just as there are poor folks in rich countries. It may be a thin slice but it exists. High-end hospitals in India can afford to buy this US $20,000 ECG machine. But what about the remaining 90% of Indians who are non-consumers of this machine. Why aren’t they consumers? The first and the most obvious reason is affordability. A single ECG scan costs US $200, an amount that 90% of the rural poor in India who earn just US $2 or less a day, simply cannot afford to pay. But affordability is not the only reason. Accessibility is also an issue for many people. Not all hospitals in rural areas can afford to buy it, or there may not be enough trained personnel to operate it. However, if you can do exponential innovation, if you can do breakthrough innovation, if you can do nonlinear innovation, if you can do Box 3 innovation, you can unlock tremendous value.

That is exactly what GE did with its innovation of a US $100 backpack-mounted ECG machine. When I went to work for GE in 2008, one of the very first projects we worked on was this ECG machine on which a single scan costs just 10 cents. Even if I am making only US $2 a day I can afford it. This machine is extraordinarily lightweight–it weighs less than a can of Coca-Cola. It can produce 750 scans on a single battery charge. Finally, this US $100 ECG machine is extremely simple to use. It has only two buttons: a green button and a red button. You push the green button to start the machine and the red button to stop it. If you know how to read traffic signals, you should be able to operate this machine. GE has converted a large number of non-consumers to consumers in India with this US $100 ECG machine.

Emerging markets represent a huge customer discontinuity. Customers in emerging markets are fundamentally different from customers in developed markets, and because they are fundamentally different, they will demand Box 3 innovation.

Opportunities for Innovation

Thus far, Indian companies have directed their innovation for Western firms. The time has come for Indian companies to focus on non-consumers in India and really unlock value through “boxing” innovation. On planet earth today, there are seven billion people, of whom only two billion have the purchasing power to buy the goods and services that corporations make. There are five billion non-consumers who represent the single biggest growth opportunity for corporations. And most of these non-consumers are in emerging markets. India accounts for one billion of them. This is perhaps the single biggest opportunity for Indian companies. Who understands the problem of non-consumers in India better than they do?

Box 3 is about creating the market. Box 1 is the market share game. Both are terribly important. In fact, if you look back at the last two decades, Indian companies have created several Box 3 innovations; they have created non-linear innovation. For instance, India has the lowest telecommunications tariffs in the world, thanks to competition among companies and their innovative offerings and pricing. Another example of a Box 3 innovation is Arvind Eye Care’s US $200 cataract surgery operation. Cataract surgery in the US would cost at least US $5,000. Narayana Hrudayalaya, another Box 3 innovator, performs open heart surgery for US $3,000 whereas in the US a similar procedure costs US $150,000. The evolution of the IT services company is one more powerful example. Twenty years ago, a Box 3 insight–a breakthrough idea–resulted in the emergence of the global IT services delivery model, whereby 10% of the work was done closer to the American customer, where the cost structure is very high, and the remaining 90% was done in India, where the costs were dramatically low and capabilities were dramatically high. Think how much value we have created based on that single Box 3 insight, how many jobs we have created, how much prosperity we have created.

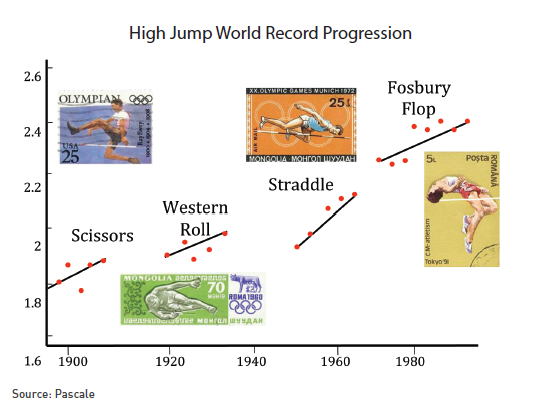

If what I am describing to you is so simple to understand, why is it so hard to do? Let me illustrate the difficulty by taking a metaphor from sports. The Olympics started in 1896, so we have about 100 plus years of data on it. When you plot the data on Olympic gold medal winners in the high jump, what you immediately see is that there have been four Box 2-Box 3 transformations in the high jump category. Only when there was a non-linear, stylistic innovation in the high jump, or a Box 3 innovation, could the high jumper go to the next level of performance. In fact, the first style used in the high jump was the scissors technique. It involves a hurdling motion. When this is the style in the high jump industry and you are a high jumper with a job to do, what do you do? Accept the rules of the scissors method and become the number one in scissors in the world. This is what I call the Box 1 challenge. Using this metaphor, we can say that inside Indian corporations today there are lots of scissors. Box 1 is about continuously improving the performance of the scissors. Is it important for us to do so? I would say it is absolutely critical.

Say, for example, that GE Healthcare views its US $20,000 ECG machine as its scissors. It better allocate its resources to make those scissors perform even better. Why? Because they still have many more useful years left. The US $20,000 ECG machine is marketed in the US and is even sold in high-end hospitals in India. You have to make your current scissors perform even better. But 100% of the resources you allocate today cannot be towards perfecting the scissors. You can do that only if you are confident that there will never be any further non-linear changes in the world. But that is not the case. Disruptive technologies will transform industries. Non-traditional competitors will enter your space. That is why, in addition to improving the efficiency of your scissors, you must do at least a few Box 2/ Box 3 breakthrough innovation experiments.

Going back to the high jump, if there had been no non-linear innovations in the high jump in the past 100 years, high jumpers would not have been able to achieve the performance that they are achieving today. Why? Because scissors is a hurdling motion. When you use a hurdling motion, the centre of gravity will define how high you can lift your body. There is only so much Six Sigma you can do to improve that. If you want to beat the centre of gravity, you have to change the model. That is exactly what somebody did with the western roll, which changed the direction of approach to the bar. The western roll allowed jumpers to capture new world records and was in vogue for about 25 years until someone invented the eastern roll, which came to be called the straddle. That was in vogue for about 25 years until Dick Fosbury invented a revolutionary technique that came to be known as the Fosbury flop. It was a head-first, back-to-the-bar technique involving a mid-air twisting motion and a backwards landing that allowed Fosbury to set a new world record. If you stop to think about it, the Fosbury flop is the most illogical way to do a high jump. This is the central challenge for leaders and future leaders in India. You must put in a lot of resources today to make your current scissors even more efficient, but you must also put in resources today to transform your scissors into a Fosbury flop.

Twenty years ago, a Box 3 insight–a breakthrough idea– resulted in the emergence of the global IT services delivery model, whereby 10% of the work was done closer to the American customer, where the cost structure is very high, and the remaining 90% was done in India, where the costs were dramatically low and capabilities were dramatically high. Think how much value we have created based on that single Box 3 insight, how many jobs we have created, how much prosperity we have created.

Closing the Possibility Gap through Next Practices

To return to the box concept, Box 1 is about closing the performance gap, and this is done through what I call linear innovation–Six Sigma, operation excellence, total quality management, lean management, etc. Box 2 and Box 3 are about closing the possibility gap. You cannot close the possibility gap by using the principles that you used to close the performance gap. You have to engage in non-linear innovation, you have to engage in exponential innovation, you have to engage in breakthrough innovation.

In India, our possibility gap is much bigger than our performance gap. For India to be a great country in the year 2025, what are Indian companies doing today to address the possibility gap? When I work with CEOs of Indian companies, I typically say this to them: I know that you are implementing a lot of projects today. Out of those projects, can you name three projects that you are implementing today that will make you a leader in the year 2025? If the CEOs tell me they are working on total quality management, time-based competition, enterprise resource planning or operation excellence to become a leader in the year 2025, I tell them: Welcome to 1970! These are Box 1 ideas. They are nothing but table space performance issues.

Box 1 is about closing the performance gap, and this is done through linear innovation–Six Sigma, operation excellence, total quality management, lean management, etc. Box 2 and Box 3 are about closing the possibility gap. You cannot close the possibility gap by using the principles that you used to close the performance gap. You have to engage in non-linear innovation, you have to engage in exponential innovation, you have to engage in breakthrough innovation.

Another word for performance management is best practices benchmarking. Best practices benchmarking is not strategy. Think about what happens in best practices benchmarking. Let’s go back to the high jump metaphor for a moment. What is best practices benchmarking in the context of the scissors technique? You look at others doing scissors and then ask yourself whether there is anyone who is doing it a little bit better, a little bit smarter than you. Then you measure the gap between yourself and the leader in scissors and put in place programmes to close the gap. Imagine what you are going to look like at the end of that process. How can you aspire for leadership in the year 2025 by doing only that?

In my view, strategy is about creating next practices. It is not about adopting the best practices of industry leaders today. The US $100 ECG machine is not a case of best practices benchmarking, it is next practices. The Fosbury flop is not a linear improvement over the scissors, it is a non-linear change. Another example of next practices is the microfinance revolution that Dr. Mohammed Yunus unleashed in Bangladesh in 1983, and for which he won a Nobel Prize in 2006. He revolutionised the microfinance sector by converting 166 non-consumers of banks into banking consumers. He patiently wrote down all the best practices of the leading commercial banks in the world. Then he started his microlending institution, the Grameen Bank, with exactly the opposite rules. He said the best practices of the leader cannot convert non-consumers into consumers. Simple common sense told him that the next practice has to be the opposite of the current best practice. Grameen Bank is very profitable. In fact, it made money even during the 2008-2009 financial crisis. It was the only bank that did not require government bailout money. The only year it didn’t make money was in 1983, its startup year.

The bank’s business model is based on common sense. Depositors become borrowers and are put in a self-help group of nine people. The self-help group decides who among them receives the US $25 loan. There is no need to submit a loan application. This means that there is no need for risk officers in Grameen Bank. And Grameen Bank has no intention of taking anyone to a court of law if they don’t repay. How then do they manage to have a 99% recovery rate? The answer is peer pressure. If anyone in the self-help group defaults on the US $25 loan, that group cannot get another loan ever again.

In my view, strategy is about creating next practices. It is not about adopting the best practices of industry leaders today. The US $100 ECG machine is not a case of best practices benchmarking, it is next practices. The Fosbury flop is not a linear improvement over the scissors, it is a non-linear change.

I was talking to the management team in Grameen Bank recently and I asked them whether they had created any other next practices since 1983. They replied, “We only do next practices, we only do Box 3. We never benchmark ourselves against other commercial banks.”

The One-sheet Strategic Plan

When I work with companies, I ask them to show me their strategic plans. Typically, what I get is a 25- inch thick binder. You can’t prepare something of this kind for Box 2/ Box 3. It makes absolutely no sense because so much is unknown and unknowable about the future. The document that you should prepare in order to be ready for the future is what I call strategy and it should be on a single sheet of paper. This way, you can get the whole organisation aligned behind you. And on that single sheet of paper you have to have five bullets:

- Non-linearity: Taking a look at the next two decades, who are the non-consumers today who can potentially become consumers, thereby demanding Box 3 innovation? What might be the disruptive technologies that will open up possibilities for you over the next two decades? Who might be the new competitors or nontraditional competitors who could enter your space? It is important to remember that this is not a prediction exercise but one of imagining the future, that is; making hypotheses about the future. The job of leaders is to collect evidence to test hypotheses. You never develop these hypotheses in a vacuum; you develop them based on what I call weak signals. Using the weak signals, can you develop hypotheses about the future? The best way to predict the future is to create it yourself. And if you want to create your future, you first have to imagine it. This aspect of the organisational strategy is the collective hypothesis about potential non-linearities.

- Strategic intent: A good example of strategic intent is Dr. Mohammed Yunus’s declaration in 1983 that he wanted to “put poverty in a museum” before he died. That is his life’s intent. Perhaps it is a 75-year intent. What is the intent for your organisation?

- Core competencies: What are you good at as an organisation?

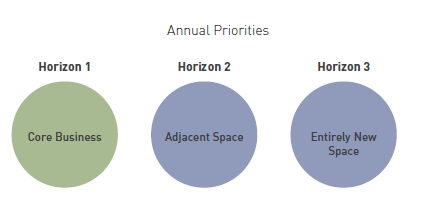

- Annual priorities. This is very important. What are the projects you are executing today? The projects you are executing today cannot all be in Box 1; they should be in three horizons. How many are in Horizon 1, which is about strengthening the core? My view is that it is very important to invest in and strengthen the core business. My rule of thumb is that anywhere from 40% to 60% of the resources should go towards growing the core. Horizon 2 and Horizon 3 are examples of Box 3 ideas. In Horizon 2, you are growing the adjacencies. Here, you are taking your current core competence and pushing it outside of your core into an adjacent space. It could be an adjacent product space, adjacent customer space or adjacent geography space. Horizon 3, on the other hand, is to do with entirely new business models.

The difference between Horizon 3 and Horizon 2 is that Horizon 3 is riskier. Adjacency growth (Horizon 2) is not terribly risky because you are taking your current core competence, which you understand well, and pushing it into an adjacent space. Horizon 2 is one step removed from your core, whereas Horizon 3 is three or more steps removed from your core. My rule of thumb is that anywhere from 25% to 35% of the projects you are executing today should be in Horizon 2. What about Horizon 3? How many projects fall into this category? My rule of thumb is that anywhere from 10% to 20% of the risk you are allocating today should be in Horizon 3. It is several steps away from your core and hence more risky.

- New core competencies: You cannot get to the future by only leveraging your current competence. Part of competing for the future is about your competency building agenda.

If you can get these five bullets on a single sheet of paper, you can get the whole organisation aligned behind you.

Testing your Strategic Intent

The best way for me to talk about strategic intent is to first talk about what it is not. Strategic intent is not the generic “motherhood and apple pie” kind of mission statement. When you’ve seen one of those, you have seen them all. Your strategic intent must pass three tests.

- Test of Direction: The reason generic mission statements fail this test is that if you strike out the name of one company and stick in another company’s name on the mission statement, it still applies. When I talk about direction, it is about the big picture. The beginning of every journey should have the end in sight.

- Test of Motivation: We must create a compelling reason for each and every employee in our organisation to wake up in the morning and say: “I can’t wait to get to work because I am so terribly important to the unit. My core competency means so much to my team and what I am doing there is something I believe in, something that has deep personal meaning for me.”

- Test of Challenge: I believe that good employees like challenges. Good employees don’t want to keep on reengineering the present.

A particularly good example of strategic intent, one that passes the tests of direction, motivation and challenge, is a statement by Former US President John F. Kennedy. When Kennedy stood up in the early 1960s and said that America would put a man on the moon and bring him back before the end of the decade, all three elements were present–direction, motivation and challenge. Strategic intent is about thinking big. It is about thinking bold. It is about dreaming big. It is about having a big ambition. It is about having an unrealistic goal. Why do you need an unrealistic goal as a starting point for Box 2/ Box 3 thinking? It boils down to common sense. As human beings, our performance is a function of our expectations. We rarely exceed our expectations. If India has to become a great country in the year 2025, we must first imagine that greatness. If all that we can imagine is a mediocre India by the year 2025, that is the very best we will end up achieving. If your corporation has to be a great corporation–a leader in the year 2025– you must imagine that leadership first. If all that you can imagine is a mediocre company in 2025, that is the very best you will end up with.

*Excerpted from the talk, “Three Box Solution: A Strategy for Leading Innovation,” delivered at the Dean’s Speaker Series lecture at the ISB in January 2016.