Both researchers and practitioners have implicitly assumed that in fluid team settings, members who are familiar with each other perform better in the short run. However, there may be diminishing returns to working with familiar teams in the long run. Experimental evidence indicates that in diverse teams, there is more exploration of knowledge, leading to higher creativity and generation of ideas. But can this lead to improved operational performance and efficiency in real-life settings?

This question becomes important in many operational contexts such as ambulance services, police patrol, terrorism and disaster responses, catastrophe management and healthcare emergencies. Operations such as these require short term collaborations where teams are regularly assembled and disbanded. These contexts necessitate coordination economies, whether through learning from doing or through the larger scope of activities, for example, in different types of trauma situations.

Professor Sarang Deo and his co-authors examine this debate in their research paper “Learning from Many: Partner Diversity and Team Familiarity in Fluid Teams”. For a standard process like patient handover in an emergency section of the hospital, pre-existing reporting forms are used. Hence, the knowledge here is codified and the scope for a new member to learn on a diverse team is limited. However, other situations like picking up a patient from the narrow alley of an apartment complex and transferring him or her to a stretcher may be more idiosyncratic. In less standard processes where knowledge is tacit and on the job, a new member on a diverse team may have the opportunity to learn more. The new recruit is able to gather knowledge from senior paramedics and dynamically adapt to the situation at hand.

That said, in mission-critical operations more generally, the question remains: how does one balance team diversity and familiarity to enhance operational performance? Answers to this question will inform better management of all kind of emergencies in a volatile and complex world.

London Ambulance Service

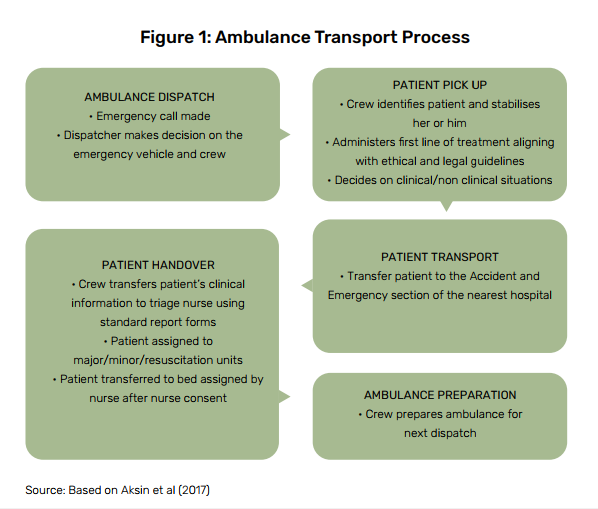

Founded in 1965, the LAS is the busiest emergency ambulance service in the United Kingdom, with some 5000 members working as staff. The researchers used London Ambulance Service data for the year 2011 for 5773 ambulance transports, made by teams comprising one of 81 new recruits and one or more of the 702 senior paramedic staff. Crew members with more than two years of experience in LAS are permanently assigned to one of the 100 ambulance stations with a stable partner and shift pattern. However, during the first two years of their tenure, new recruits are scheduled to be part of fluid teams that may need to be staffed for three reasons: first, stable partners of senior paramedics go on leave; second, the team needs extra capacity for special events and third, the need to fill not so popular shifts. Such relief rosters are composed for a 12 hour period. The ambulance service process is divided into a number of sub-processes, as Figure 1 shows: ambulance dispatch, patient pick up, patient transport, patient handover and ambulance preparation. As is evident from Figure 1, there are a variety of medical and non-medical considerations that paramedics have to take into account during the pick-up process. For instance, for a patient with cardiac arrest, there may be an immediate need to administer cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

For a standard process like patient handover in an emergency section of the hospital, pre-existing reporting forms are used. Hence, the knowledge here is codified and the scope for a new member to learn on a diverse team is limited.

But for a non-English speaking geriatric patient with diarrhoea, the challenge may be to understand the clinical history of the patient. The degrees of freedom in the pick-up process rule out an explicit standard operating procedure. The paramedics make impromptu decisions based on their judgment and the emergency at the pick-up scene. Less standardised processes such as this have been called ‘divergent processes’ by authors such as Shostack (1987).

On the other hand, the patient handover process requires reporting in standard forms while transferring the patient to the Ambulance and Emergency (A&E) section of a hospital. Since the patient handover process is fairly standardised and is based on pre-existing protocol, the paramedics rely on their skills only if they are more efficient than the prescribed protocol. A paramedic is able to make this judgment after having acquired considerable experience. A new recruit does not have equivalent opportunities to witness new methods during handover. Even if the new recruit has a more efficient idea or method, it is unlikely to be favoured by senior paramedics over existing protocol.

This variation in standardisation renders salient the critical role of teams and their structure. The optimal match between standardisation of task and team diversity is the question that these researchers investigate in their paper.

The researchers find that in a fluid team setting, members with diverse experience perform better operationally. Moreover, the beneficial effects of partner diversity begin to accrue after the paramedic has gained significant experience in terms of the number of ambulance transports performed.

Optimal Team Composition

Given the divergent nature of the pick-up process, a new recruit on the relief roster team can learn new techniques applied by different senior paramedics. In turn, he or she can add his learning from previous teams to the knowledge pool of the team. What is more, the new recruits’ ideas are also likely to be actually implemented, thereby resulting in improved operational performance. Summarising this, the researchers (2015:10) hypothesise that “prior partner diversity positively impacts paramedic performance during the non -standardised patient pick-up process by reducing average time for pick-up”.

In contrast, for a more standardised patient handover process, the emergency crew has to follow the standard operating procedure. A new recruit can override the process and provide important clinical and non-clinical details to the triage nurse only if she or he has sufficient ambulance transport experience. Thus, the researchers examine whether prior partner diversity positively impacts paramedic performance during the standardised patient handover process by shortening handover times, provided that individual experience is more than 150 ambulance transports.

The authors’ analyses of the LAS data first confirm the benefits of prior partner diversity on the team. The results show that new recruits on the roster relief team with diverse partner experience spend 2.7 minutes lesser than a familiar team for the pick-up process. This is an 11% reduction in time over a baseline of 30 minutes.

Second, for the patient handover process, there is a 22% reduction in the operational time if the recruit has performed more than 150 ambulance transports. This supports the second claim. In addition, for every 100 transports with the same partner, handover time is reduced by a minute. The handover time goes down by roughly 1.5 minutes for every 100 additional transports undertaken by the new recruits.

Diversity versus Familiarity? The Way Forward

The study is rich in managerial implications. Management of fluid teams makes partner stability difficult to achieve. In such a setting, the manager would benefit from understanding the effect of partner diversity and team familiarity on the team’s performance.

To measure the impact of partner diversity and team familiarity on operational performance, the authors have devised two counterfactual strategies. In the partner focussed strategy, a new recruit on the team works with a stable partner for all transports. The partner diverse strategy, on the other hand, allows new recruits to take turns while working with different senior paramedics in their zone. This study unifies these perspectives and provides empirical evidence on the simultaneous effect of both mechanisms (team familiarity and prior partner diversity) on operational performance of teams using field data. The importance of the two mechanisms cannot be overstressed. They have a bearing on organisational recruitment strategies and on learning and development activity within organisations over time.

Other managerial implications follow from the above. First, in the specific empirical setting of the London Ambulance Service, the findings of this paper show that a team formation strategy that encourages partner diversity can outperform one that encourages team familiarity. The magnitude of improvement (about two minutes) is likely to have a significant impact on patient outcomes.

Second, for more general service settings, such as in disaster response teams or in R&D teams with tight deadlines and an emergency mandate, these results highlight the need for managers to balance the beneficial effects of team familiarity and partner diversity. Managers can analyse the work history of their employees, for example on questions such as who has worked with whom in the past and on what tasks, using human resource analytics. Similarly, performance in these roles is routinely captured by enterprise IT systems (Huckman and Staats 2013). These two bits of information together can help managers make the optimal team formation decisions.

Such issues assume more importance in contexts such as Indian healthcare where the system lacks modern infrastructure, inhibiting access to quality healthcare. A study conducted in a South Indian city reported that in 50% of trauma cases, no prehospital care or treatment was offered by qualified paramedics when ambulances were used to transport patients to hospitals (Sharma and Brandler 2014). In other words, the emergency medical system (EMS) has been ineffective due to poor infrastructure, the lack of trained and coordinating prehospital personnel, and lack of access to services.

The degrees of freedom in the pick-up process rule out an explicit standard operating procedure. The paramedics make impromptu decisions based on their judgment and the emergency at the pick-up scene.

The findings of this study apply especially to emergency situations, in healthcare or otherwise, where it may not be possible to function optimally as per standard operating protocols. Such situations heighten the criticality of fluid teams and of their underlying heterogeneity and/or homogeneity. The researchers extend prior work showing that diverse teams might bring efficiencies to emergency operations.

The analysis from this study also confirms the previously identified benefits of team familiarity. For a manager of a fluid team, like an EMS ambulance or a cyclone disaster response team, or other turbulent settings where stable partnerships might be difficult to ensure, understanding the potential benefits of team diversity can be valuable. This can be balanced with familiarity, to ensure optimal team composition.

Managers can analyse the work history of their employees, for example on questions such as who has worked with whom in the past and on what tasks, using human resource analytics. Similarly, performance in these roles is routinely captured by enterprise IT systems. These two bits of information together can help managers make the optimal team formation decisions.

To what extent organisations will recognise diversity and trade it off with familiarity becomes moot. A second order issue is to build the required human capital and sustain it with ongoing assessment, learning and development processes on a 360 degree appraisal platform.

Anubrata Banerjee is a freelance writer with the Centre for Learning and Management Practice at the ISB.

For Further Reading

Aksin, O.Z., Deo, S., Jónasson, J.O. and K Ramdas (2015). Learning from Many: Partner Diversity and Team Familiarity in Fluid Teams. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2672133

Huckman, R and B Staats (2013). The hidden benefits of keeping teams intact. Harvard Business Review, 91(12): 27.

Sharma, M and E S Brandler (2014). Emergency medical services in India: the present and future. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 29(3): 307-310.

Shostack, GL (1987). Service positioning through structural change. Journal of Marketing, 1987: 34-43.