Increasing international trade between nations has coincided with a surge in MNFs conducting their R&D activity overseas in countries such as India and China. Fortune 500 firms have about 100 R&D laboratories in China and about 63 in India. Moreover, according to a survey by The Economist, about 83% of the new R&D centres added by Fortune 1000 firms are located in India and China. This trend, surprisingly, has continued despite concerns of weak IP regimes in these countries and is primarily driven by a need to access the talent and knowledge available in these countries. In the same survey, about 84% of the surveyed managers were of the opinion that a weak IP regime was a major impediment in conducting R&D in these countries. In a series of papers we explored this rather paradoxical trend: How do MNFs manage to conduct R&D at host destinations such as India and China despite concerns over not being able to protect their innovations?

Perhaps one of the ways MNFs manage to offshore R&D even when IPR at the host destination is weak, is to carefully choose the projects that are offshored such that the knowledge involved is less amenable to being leaked out to competitors. In order to understand when IPR matters for offshoring of R&D and when it does not, we first looked at whether projects that are offshored to weak versus strong IPR destinations systematically differ in their characteristics.

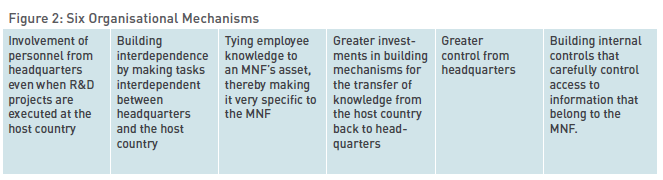

We first studied whether the strength of a country’s IPR matters for offshoring R&D activity, and if so, for which kinds of activity. To this end, we distinguished between home projects, whose fruits are likely to be used in the country, where the MNF is headquartered, versus host projects, which are those whose fruits are more likely to be used in the host destination. Since leakage primarily happens through the hiring away of key inventors by rivals, the extent to which rivals can expropriate an MNF’s ideas should be of relevance. Thus, if it is likely that rival firms in the host country can expropriate and utilise ideas from host projects relatively more easily than home projects, which are often targeted at more sophisticated customers in the country in which the MNF is headquartered, home projects should be less prone to leakage than host projects. It would be reasonable to assume, therefore, that such projects are less affected by the strength of the host country’s IPR than host projects.

The results of this study suggest that the strength of the IPR at a host country matters only when the fruits of the offshored R&D effort are likely to be also used in the same host country, whereas they do not matter if they are likely to be used in the country in which the MNFs is headquartered.

Using the number of inventors from the host country that participated in an innovation as our proxy for the extent of offshoring, we investigated whether the number of inventors from an offshore location was lower on projects that were prone to leakage versus those that were not. We also made a similar comparison between projects that were offshored to countries with a strong IPR (such as the UK and Germany) and those that were offshored to destinations with a weak IPR (such as India or China). Indeed, as expected, the results of this study suggest that the strength of the IPR at a host country matters only when the fruits of the offshored R&D effort are likely to be also used in the same host country, whereas they do not matter if they are likely to be used in the country in which the MNFs is headquartered (see Figure 1). Consider, for example, the case of Texas Instruments (TI), which set up an R&D captive centre in India way back in the 1980s when the country’s patent laws were very weak. Our results, which are also substantiated by interviews with managers, suggest that it was quite practical for TI to offshore R&D to India as long as the fruits of the R&D effort were more likely to be utilised in the US, given that the threat of its IP leaking out to competitors was low on such projects.

We also examine whether the strength of the IPR at the host country also alters the nature of the R&D projects offshored to that country. In particular, we further explored whether projects that are offshored to host countries with a weak IP regime systematically differed on two dimensions that we uncovered from our interviews: 1) the extent to which they build on prior knowledge belonging to the same MNF or internal knowledge based projects, and 2) the extent to which the output of the R&D effort was likely to be firm specific. We found that whereas MNFs offshore R&D projects that are less likely to offshore internal knowledge-based projects, they were more likely to offshore firm-specific projects to host countries that had a weak IPR. This provides us with a critical piece of the puzzle of how MNFs manage to offshore R&D to destinations such as India and China, and that is through the use of very sophisticated project selection mechanisms.

A critical piece of the puzzle of how MNFs manage to offshore R&D to destinations such as India and China, and that is through the use of very sophisticated project selection mechanisms.

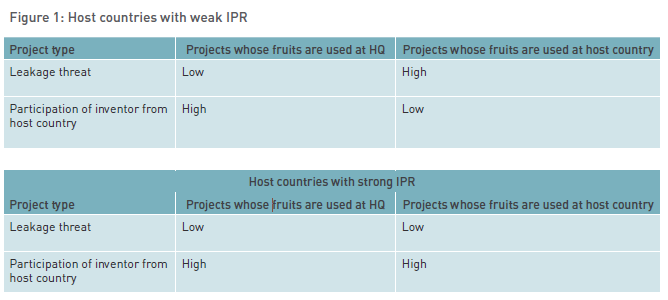

Finally, in another ongoing project, we explored other organisational mechanisms that MNFs use to ward off the threat of leakage when offshoring R&D activity to destinations with weak IPRs. In particular, our focus in this project was to understand the organisational mechanisms firms use to protect knowledge that is not patentable from leaking to rivals in a host country. Using several interviews with managers in India, China and the US, and survey data from captive R&D centres of MNFs in India, we unearthed six organisational mechanisms that help MNFs protect unpatented knowledge (see Figure 2).

Our research shows that MNFs adopt a variety of organisational mechanisms to prevent or delay leakage when the host country’s legal IPR is weak, and this is another strategy by which MNFs are able to offshore R&D to destinations such as India and China despite a relatively higher risk of knowledge leakage.

From these studies, we can see that MNFs use a variety of project selection and organisational mechanisms to compensate for weak legal IPR in host destinations. It is widely believed that MNFs may not be willing of offshore R&D activity to host locations that are more prone to leakage. Our research concludes that this is not the case. The organisational and project selection mechanisms described above give MNFs the confidence that they can prevent both patentable and unpatentable knowledge from leaking out to rivals, thereby making offshoring of R&D activity possible even when the legal mechanisms to protect knowledge are either non-existent or weak. This tells us that strategies to protect knowledge that may be effective in the West, where legal institutions are relatively stronger, might need some rethinking or tweaking by MNFs when operating in the East.