Why do governments repay external sovereign borrowing? Models where countries ser vice their external debt for fear of being excluded from capital markets for a sustained period seem ver y persuasive, yet are at odds with the fact that defaulters seem to be able to return to borrowing in international capital markets after a short while. With sovereign debt in industrial countries at extremely high levels, understanding why sovereigns repay foreign creditors, and what their debt capacity might be, is an important concern for policy makers and investors around the world.

A Theory

A number of recent papers offer a persuasive explanation of why rich industrialised countries ser vice their debt without being subject to coordinated punishment. As a countr y becomes more developed and moves to issuing debt in its own currency, more and more of the debt is held by domestic financial institutions or is critical to facilitating domestic financial transactions. Default on domestic bond holdings now automatically hurts domestic activity by rendering domestic banks insolvent or reducing activity in financial markets (see Bolton and Jeanne, 2011 or Gennaioli, Martin and Rossi, 2011). If the government cannot default selectively on foreign holders of its debt, either because it does not know who owns what or cannot track sales by foreigners to domestics (see Guembel and Sussman, 2009 and Broner, Martin and Ventura, 2010 for rationales), then it has a strong incentive to avoid default and make net debt repayments to all, including foreign holders of its debt.

What is less clear is why an emerging market or a poor countr y that has a relatively underdeveloped financial sector, and hence little direct costs of default, would be willing to ser vice its debt. Government short termism may explain this. We argue in Achar ya and Rajan (2011) that myopic governments seeking electoral popularity can nevertheless commit credibly to ser vice external debt. Short horizon governments do not care about a growing accumulation of debt that has to be ser viced – they can pass it on to the successor government – but they do care about current cash flows. So long as cash inflows from new borrowing exceed old debt ser vice, they are willing to continue ser vicing the debt because it provides net new resources. Default would only shut off the money spigot for much of the duration of their remaining expected time in government.

Thus, we have a simple rationale for why developing countries may be able to borrow despite the absence of any visible mode of punishment other than a temporar y suspension of lending; lenders anticipate the developing countr y will become rich, will be subject then to higher domestic costs of defaulting and

will eventually ser vice its accumulated debt. In the meantime, the countr y’s short horizon government is unlikely to be worried about debt accumulation, so long as lenders are willing to lend it enough to roll over its old debts plus a little more. Knowing this, creditors are willing to lend to it today.

Key in this narrative are the policies that a developing countr y government has to follow to convince creditors that it, and future governments, will not default. To ensure that the countr y’s debt capacity grows, it has to raise the future government’s ability to pay (that is, ensure that the future government has enough revenues) as well as raise its willingness to pay (that is, ensure that the future penalties to default outweigh the benefits of not paying). The need to tap debt markets for current spending gives even the myopic government of a developing countr y a stake in increasing debt capacity. The policies that it follows will, however, potentially reduce the countr y’s growth as well as increase its exposure to risk.

Interestingly, as the rate at which a government discounts the future falls (i.e., becomes less myopic), its willingness to default on legacy debt increases. The long horizon government internalises the future cost of paying back new borrowing, as well as the distortions that stem from policies required to expand debt capacity. This makes borrowing less attractive, and since for a developing countr y government the ability to borrow more is the only reason to ser vice legacy debt, the long horizon government has more incentive to default (or less capacity to borrow in the first place). Similarly, developing countries with more productive technology may also have lower debt capacity because the distortionar y taxation needed to sustain access to debt markets will be more costly for such countries.

Implications

Because the costs of default are sizeable in our model only when the countr y becomes rich, the nature of developing countr y defaults and rich countr y defaults are likely to be ver y different. Developing countries are more likely to default when revenue shortfalls or increases in expenditure lead to a buildup of debt that can imply net debt outflows for some time. The reason for default is not that the countr y cannot pay but that the time path of prospective payments does not make it worthwhile for the current government to maintain access to debt markets. For rich countries, however, the direct cost of default is substantial, and default looms only when the countr y simply does not have the political and economic ability to raise the revenues needed to repay debt.

The ongoing sovereign crisis in Europe raises some fundamental issues that our model can speak to. For instance, our model explains why some governments keep current on their debt, even when most market participants suggest that it would be better for them to default. So long as the Euro area and multilateral institutions are willing to provide funding to tide the countr y over, myopic governments see no benefit in default, no matter how much debt accumulates. That does not mean, however, that ser vicing debt or taking actions that maintain or expand long-term debt capacity are optimal.

For rich countries, the direct cost of default is substantial, and default looms only when the countr y simply does not have the political and economic ability to raise the revenues needed to repay debt, as in the case of Greece. When rich countries are in danger of default, outside agencies that lend them more without helping these countries expand productivity and growth are only postponing the inevitable messy restructuring. Rich countr y defaults are more likely to be solvency defaults rather than liquidity defaults, and a simple rescheduling of debt without significant haircuts to face value is unlikely to help the countr y regain access to private markets.

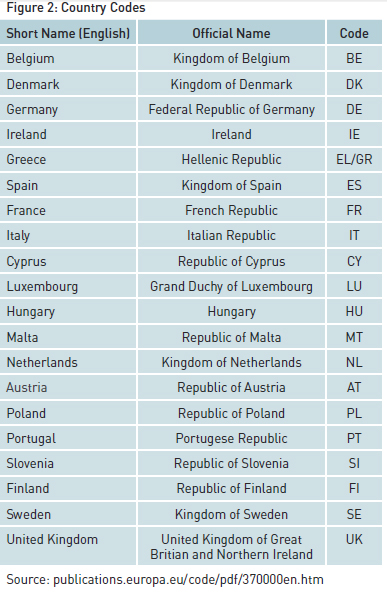

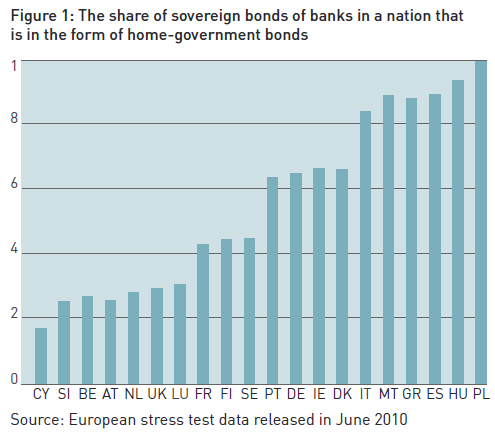

Another interesting development in the ongoing sovereign debt crisis in Europe is the extreme degree of dependence of the health of a countr y’s banking sector on the health of the government, and vice versa. Achar ya, Drechsler and Schnabl (2010) document that the 91 European banks stress-tested in 2010 held sovereign bonds on average up to a sixth of their risk-weighted assets, and that within these sovereign bond holdings, there was a “home bias” in that banks held a substantial portion in their own government bonds (see Figure 1; for information on EU countr y codes please see Figure 2). Indeed, the home bias in sovereign bond holdings was the highest for countries with the greatest risk of government debt default, suggesting they are positively correlated. Countries that are at greater risk of default also have banks whose portfolios are stuffed with their own government debt.

One explanation is that banks are buyers of last resort for their government’s debt, and this is why risky countries that find no other takers, stuff their banks with their paper. An alternative explanation (see Diamond and Rajan, 2011) is that banks have a natural advantage in loading up on risks that will materialise when they themselves are likely to be in default. However, a third, not mutually exclusive, explanation is ours − that countries have to prove to new bondholders their enduring resolve to ser vice their foreign debt, and this is best done by making the costs of default on domestic debt prohibitively costly.

In this vein, consider the recent proposal of the Euro area think tank, Bruegel, for Euro area sovereigns to issue two kinds of debt, one (blue bond) that is guaranteed by all Euro area countries and will be held by domestic banks, and another (red bond) that is the responsibility of the issuing countr y only and which domestic banks will be prohibited from

Countries that are at greater risk of default also have banks whose portfolios are stuffed with their own government debt.

holding. Our model points out that there is ver y little reason for a countr y to ser vice the red bonds. These will not be held by key domestic financial institutions, and therefore, will not cause many ripples if they are defaulted on. This will make it hard for a countr y to borrow sizeable amounts through red bond issuances, which may indeed be the subtle intent of the proposal.

Acharya, Viral V., Itamar Drechsler, and Philipp Schnabl. “A Pyrrhic Victory? – Bank Bailouts and Sovereign Credit Risk.” NYU Stern Working Paper, 2010.

Acharya, Viral V., and Raghuram Rajan. “Sovereign Debt, Government myopia and the Financial Sector,” NBER Working Paper 17542, also Working Paper NYU, 2011.

Bolton, Patrick, and Olivier Jeanne. “Sovereign Default and Bank

Fragility in Financially Integrated Economies.” NBER Working Paper 16899, 2011.

Broner, Fernando, Alberto martin, and Jaume Ventura. “Sovereign Risk and Secondary markets.” American Economic Review 100 (2010): 1523-1555.

Diamond, Douglas, and Raghuram G. Rajan, “Fear of Fire Sales and the Credit Freeze.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126.2 (2011): 557-591.

Gennaioli, Nicola, Alberto martin, and Stefano Rossi. “Sovereign Defaults, Domestic Banks, and Financial Institutions.” Web. 2011. http://crei.cat/people/gennaioli.

Guembel, Alexander, and Oren Sussman. “Sovereign Debt Without Default Penalties.” Review of Economic Studies 76 (2009): 1297-3120.