Credibility of the implementers and acceptance by the intended target groups, apart from the speed of implementation itself, are critical to the success of any grassroot administrative reforms. This article examines the strategic approach underlying the District Results Framework Document (RFD), an ex-ante performance management and accountability instrument for District Collectors, and the lessons from processes & events that led to a shift vis-à-vis performance management at the level of public policy implementation in the state of Punjab.

Attempts at administrative reforms in the government sector have seen little success in India. First, it is not easy to get political backing. In case political support is obtained, the reform measure may face red tape. Even if it gets implemented it may not reach its logical conclusion, for one or the other reason as evidenced by a number of studies as well as anecdotal evidence (Peters 1988; Durant 2008; Singh 2006; Francesca 2010). For instance, the Second Administrative Reforms Commission made 1500 recommendations to the Government of India, out of which 1228 were accepted. However, their implementation did not materialise on the ground in line with the intended vision (Singh 2006). Implementation issues dented the achievement of the goals. This reflects the reality in government: despite favourable political environment, many reforms just do not get implemented in letter and spirit (Peters 1998; Durant 2008). The District Results Framework Document (RFD), an exante performance management and accountability instrument for the District Collectors, faced similar challenges in the state of Punjab. This article traces the implementation of the RFD in Punjab.

The Idea

The District Collector’s (DC) office is the face of the government in India, being the first point of contact between the government and the public. The Union and State Secretariats formulate public policies; the district administration led by the District Collector (DC / Collector / Deputy Commissioner) executes them. Besides collection of revenue the implementation and monitoring of government schemes begin at this interface. Hence, the district interface is critical from many perspectives. For political interests, this is the level where the government starts delivering on the promises made to the electorate. The common public stands to either suffer or benefit from the performance of the DC. For the DC, a professional civil servant, these field tenures are crucial for shaping the career. Hence, the DC’s position is key for overall government performance.

However, in the absence of an objective performance evaluation system, high levels of subjectivity prevail vis-à-vis the performance of the DC. Instead of a robust system the DC’s personality becomes a defining factor for government performance and public interest. In addition, the pulls and pressures in the administrative ecosystem make the whole arrangement fluid. As a remedial reform measure, the ‘idea’ was to shift the pivot of DC’s performance from individual drive to a robust system – District RFD.

District RFD – A robust system of performance evaluation

District RFD is the fi rst evaluation system of its kind in India that objectively evaluates the performance of a District Collector and arrives at a single composite score on a scale of 100. This allows both public and political executives to form an objective opinion about the DC’s performance.

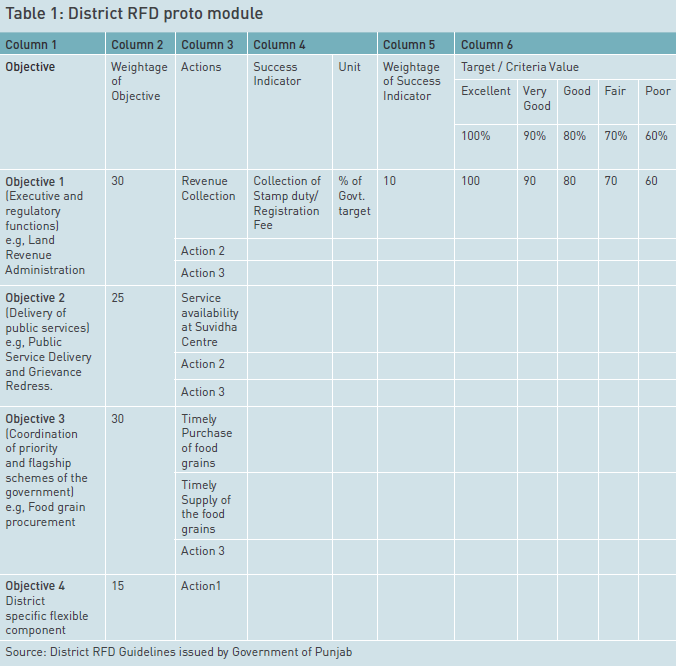

The fundamentals of District-RFD can be understood from Table 1. It focuses on the core functions (Column 1) of the DC and allows prioritisation (column 2) amongst them. In a way, it highlights the DCs priority tasks. It allows crystallisation of the functions into concrete actions (Column 3), which are measured through predefined success indicators (Column 5) across a range of acceptable achievement targets (Column 6) ranging from 60% to 100%. This does away with the dichotomous nature of performance measurement system (success or failure) to a more pragmatic performance-centric continuum approach. This in turn frees the DC from being judged arbitrarily for performance to a more transparent and rational system.

District RFD does take inspiration from the RFD system earlier introduced at the central level by the Union Government. However, District RFD is an evaluation tool at the implementation stage whereas the former applies to the formulation stage of public policy.

Evaluation Process

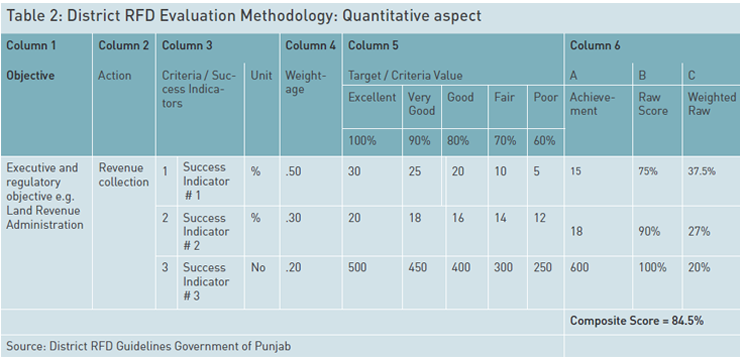

DCs are evaluated twice in a year by the Divisional Commissioner under this arrangement. They are awarded a composite score for performance. Table 2 explains the evaluation methodology. For simplicity, we have taken one objective. The raw score (Column 6B) for achievement is obtained by comparing the achievement (Column 6A) with the agreed targets. For example, the achievement for first success indicator is 15. The achievement is between 80 %( good) and 70% (fair) and hence the raw score is 75%. The weighted raw score (Column 6C) is obtained by multiplying the raw score with the relative weights (Column 4).

Advisory Task Force (ATF)

District RFD has a subsystem of quality assurance and moderation as well. ATF is an independent advisory body of specialists from diverse backgrounds including public service, defense, academia, and the corporate sector. It ensures quality in selection of targets, and checks soft targeting at the formulation stage. By recommending on force majeure cases it protects a Collector from the adverse effects of unavoidable and unforeseen complexities of the field, on his performance.

Bureaucratic response to District RFD

Notwithstanding, the political backing that District RFD had, making it a reality was a challenge. That bureaucrats were the subject as well as the object of the reform implementation process posed a classical dilemma for the reformers. Bureaucracy’s penchant for status quo and resistance to change is known (Weber 1978). Studies have shown that high level bureaucrats’ views have serious implications on the nature of challenges a reform measure faces. A number of formal and informal means are available with career civil servants to sabotage a reform measure with which they are not sympathetic (Lynn 1979). Moreover, such opposition is rarely a frontal attack; rather it resembles guerrilla warfare (Rourke 1969). This type of resistance to District RFD was anticipated and it did come. Hence a strategy was devised to achieve ‘initial survival threshold’ (Downs 2015), for which right nature of restructuring and resocialisation (Biggart 1996) of the Collectors was planned. It was decided that acceptance, honest commitment and active participation of the Collectors would be secured as a priority.

The strategy for District RFD formulation and implementation

The State Performance Management Division (PMD), an extra government body, was entrusted with the responsibility. PMD needed a leader who could instil a belief among Collectors in the uprightness and utility of District- RFD, this ‘belief ’ has a direct correlation with the legitimacy required for securing obedience amongst bureaucrats (Weber 1978). PMD identified a former Chief Secretary of Punjab as the right person for this job. He knew the system, had the necessary respect amongst the serving collectors and state bureaucracy who had the ability to convince & sense opportunity. He formed a team of three including a former District Collector and a research scholar, who had confidence in District-RFD to succeed. Two serving senior bureaucrats were also identified and convinced for the job. They were duly incentivised. This was the first step to instil a belief in District RFD amongst the serving bureaucrats.

The participative approach

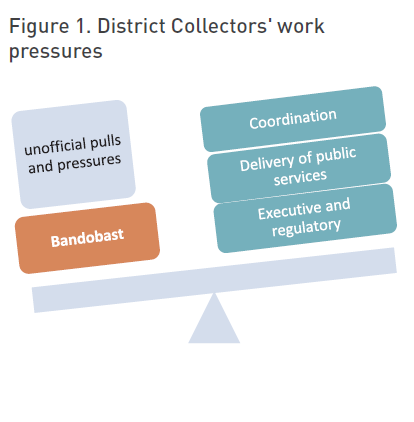

It was decided to involve the DCs to make active contributions at the very first stage of District-RFD formulation. It was an important decision; it helped in getting first-hand information at the very first place thereby saving time and setting right momentum. However, it was important that DCs give adequate time and genuine feedback on the administrative ecosystem of their district. This was ensured through one DC at a time approach initially. And later division- wise group interactions in formal and informal settings. After rounds of deliberations their core functions were broadly classified into three categories (i) executive and regulatory (ii) delivery of public services and, (iii) coordinator of priority and flagship schemes of the government. In official capacity DC should be held accountable for these specific functions only. However, on the basis of information supplied by the Collectors it was discovered that a significant amount of their time was spent on a so called largely unaccounted performance area – ‘Bandobast’ (Figure 1).

Bandobast

DCs, in the capacity of chief protocol officer, need to ensure logistical arrangements for critical political / senior bureaucratic visits in their districts. However, they were heavily engaged in delivering on similar unofficial and arbitrary visits as well – Bandobast. These visits were frequent and consumed their official time mostly at the cost of core functions of public interest. Their promotion and transfers were contingent on these visit management. Hence they would personally ensure these arrangements. In the absence of an objective performance measurement system most of the collectors had acceded to this informal system. During informal conversation most of the collectors expressed concern over the prevailing informal obligations in government set-up, including undue interference of local politicians.

Finalisation of District RFD and the guidelines

DCs showed great enthusiasm for the reform measure amidst prevailing work culture. They were offered to make the first cut on District RFD and the examinees were delighted to set their papers themselves. Cashing on this opportunity, DCs placed higher marks (85%) to core functions as mandatory performance parameters to evaluate their performance. Remaining 15% marks were kept for innovation and special circumstances, which were eventually evaluated by the ATF. This allowed them to screen arbitrary work pressures and undue political obligations and, the objective nature of this system fixed their accountability for performing core functions only. Now they had a mechanism of priortised performance to follow that provided immunity from individual preferences thereby shifting the pivot of district administration to a robust system. Thus District RFD was emerged as a dependable structure by the DCs for the DCs.

RFD a Tripartite agreement: To legitimise District RFD it was strategically decided (with the consent of DCs) to involve Chief Secretary of the state and Divisional Commissioner to sign a tripartite agreement with each DC for his District RFD. This arrangement not only highlighted the legitimate work of DCs in the eyes of entire government but also brought him under an objective accountability system. This arrangement was hence one of the major success of the implementation strategy.

Cabinet approval, RFD became a state policy: With District Collectors themselves backing the reform measure, the PMD leadership was in a good position to seek cabinet approval. And without losing the momentum gained in the process Punjab Cabinet was approached with the help of Chief Secretary, one of the tripartite signatory. A presentation was made citing how this arrangement would help the Chief Minister track the delivery of his promises to the electorate. As a result, District RFD was adopted by the state of Punjab starting April 1, 2011.

Major lessons learnt

This year-long process resulted in some pragmatic learnings. At the outset, a reform measure should be conceptualised in terms of the right mix of theory and practice. Theory allows an ideal structure; practical insights make it more acceptable. A reform statement document, with clean and comprehensive coverage of ideas, should be prepared and circulated amongst key stakeholders. Once the reform agenda is set it should be introduced through a credible top administrator, whether serving or retired. The credibility of this individual, personality traits, administrative kinship and personal equations all matter in government.

Further, the pre-reform processes should be open to the target officials. They should be involved in strategy formulation. In other words, the examinee should be involved in the process of setting the question paper. This is the stage when the target officials begin owning the reform measure.

No reform gets internalised in government systems until it has the necessary legitimacy. Acceptance of such measures trickles down from top to bottom. Hence, it must secure political backing in the form of cabinet approval/legislative provision/constitutional amendment eventually. The seat of the reform implementing body should be closest to the seat of the highest levels of authority, preferably cabinet secretariat or chief secretary’s secretariat.

Time and momentum are of the essence here, hence a concept note, strategy for implementation and a draft cabinet note must be prepared beforehand for anticipated political approval. And last, the presence of a third party independent review mechanism always helps, because it eliminates doubts and helps build faith in the target officials at large.

Public policies lose meaning without implementation, and for implementation we need the right systems. Currently, government systems in India especially in the states are still functioning with several performance management lacunae, which can become acute if not checked. Administrative reforms answer many of these gaps; however, reform processes and systems themselves may need reforms. Hence, we may start thinking about comprehensively reforming the reforms policy, to begin with.

REFERENCES

Biggart, A, & Furlong, A (1996). “Educating ‘Discouraged Workers’: Cultural Diversity in the Upper Secondary School.” British Journal of Sociology of Education, 17(3), 253-266.

Downs, D, & Robertson, L (2015). “Threshold Concepts in fi rst–year composition”. In Adler-Kassner L & Wardle E (Eds.), Naming “What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies”: 105-121. University Press of Colorado.

Durant, R (2008). “Sharpening a Knife Cleverly: Organizational Change, Policy Paradox, and the ‘Weaponizing’ of Administrative Reforms.” Public Administration Review, 68(2), 282-294.

Gains, Francesca, and Peter John (2010). “What Do Bureaucrats Like Doing? Bureaucratic Preferences in Response to Institutional Reform.” Public Administration Review 70 (3): 455–63. http://hpplanning.nic.in/RFDs%20in%20Punjab.pdf

Lynn, Naomi B, and Richard E Vaden (1979). “Bureaucratic Response to Civil Service Reform.” Public Administration Review 39 (4): 333–43.

Peters, B Guy (1998). “What Works?: The Antiphons of Administrative Reform.” In Taking Stock: Assessing Public Sector Reforms, edited by Peters B Guy and Savoie Donald J 78-107. McGill-Queen’s University Press

Singh, S (2006). “Administrative Reforms Commission and Right to Information.” Economic and Political Weekly 41(39): 4110-13.

Van Riper, Paul P (1969). Review of Review of Bureaucracy, Politics and Public Policy, by Francis E. Rourke. Administrative Science Quarterly 14 (3): 494–95.