For teenagers at the bottom of the pyramid, adopting and persisting with the Internet is the result of innovations to manage needs within means by staggering costs, scheduling time and sharing know-how. In this article, Professor Rangaswamy shares the fi ndings of her study on mobile Internet usage among teenagers from the slums of India and reveals the motivations behind, and the revolutionary impacts of, growing Internet uptake and access.*

“Mental kartha hai … when I am online, I am, like, blown away … I want to experience and download as much as I can before my prepaid times-out.” This quote from a teenager living in a Hyderabad slum, from an interview conducted three years ago, was about his Aircel micro prepay mobile Internet that lasted for three days with a download cap of 2 GB! Fast forward to the present, and Aircel’s monopoly on prepaid mobile Internet is the site of intense competition among all the major telecommunications companies (telcos) in India, each vying for a fair piece of its huge market share. This essay is not the story of telcos but of teenagers living in Indian urban slums, hungry for the Internet and its many splendoured affordances.

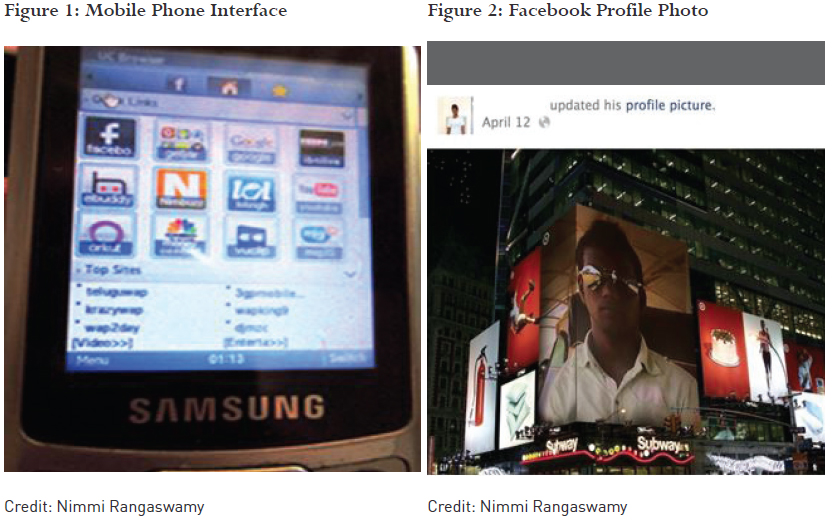

Teenagers, despite living in a resource-poor ecosystem, leapfrog digital technologies with Internet enabled devices to lead digital lives accessed on mobile phones: a leap at once discontinuous and disruptive, revolutionising their media ecology. Indeed, for many of them, the mobile phone is the inaugural personal gateway to a world of multi-media communications, entertainment and sociality. Teenagers from urban slums in India are expanding the “fixtures of teenhood”: friendship, communication, play and selfexpression (Boyd, 2007). As in other documented contexts (Ito et al., 2009), teen Internet usage is about self-directed engagements with online content for pleasure, knowledge and perpetual social contact. What is unique to this story are the paths traversed to forge an always on and perpetual contact with digital life.

It is usually acknowledged that a gap exists between technology design and technology use as users adapt and customise technology to suit their individual needs (Heeks, 2002). However, the study of an information and communications technology (ICT) device could move away from the individual user to capture the relationship between a socio-geographic context (such as an urban slum) or a cultural milieu (non-elite or underprivileged teenagers) and their underlying rules,

resources and capacities that might enable or restrict use. How grounded is the mobile Internet in such a milieu? We see energetic uptake of affordable Internet for diverse ends such as entertainment, friendship or romance even in resource-crunched ecologies. More importantly, we see the twinned stringency of spending and affluence of use as users redistribute and allocate money to purchase the Internet. The rich experience of technology is a combination of several local factors revolving around the need to create what we might call “spaces of innovation rather than any inherent properties these technologies may possess” (Tacchi, 2004, p. 99). Sonia Livingstone (2008) observes that for teenagers, the online realm represents “their” space – a space inhabited by teenagers and their peer groups presenting an “exciting yet relatively safe opportunity to conduct the social psychological task of adolescence – to construct, experiment with, and present a reflexive project of the self in a social context” (p. 397). A rapidly expanding body of empirical research is examining how people create personal profiles, network with familiar and new contacts and participate in various forms of online community (Boyd, 2006). In the context of the developed world and in the stable comforts of middle-class life, youth want to be in “perpetual” contact via texting, instant messaging, mobile phones and Internet connections. This continuous presence requires ongoing maintenance and negotiation. How much of this is true in the far less privileged context of the urban slum in India?

Data ethnography

Urban slums in India always boast of their proximity to city centres and their vast public infrastructures, though they themselves stand on unauthorised land and have no claims to legal citizenship. This essay is based on a three-year-old study (Rangaswamy and Cutrell, 2012; Rangaswamy and Yamsani, 2011) conducted in the slums of Hyderabad, Chennai and Mumbai. We adopted an ethnographic approach to data collection through in-context observations and in-depth interviews with mobile shop owners and their customers. We focussed on 22 customers, all males between the ages of 15-22, who used the mobile Internet in varying degrees and were randomly selected from the daily footfall of clients in these shops. Of this group, 10 were in high school and two in college, and eight of the 12 had part-time jobs. The remaining 10 had discontinued their studies and were employed full-time or part-time. Two of the 10 were self-employed.

Teenagers, despite living in a resource-poor ecosystem, leapfrog digital technologies with Internet enabled devices to lead digital lives accessed on mobile phones: a leap at once discontinuous and disruptive, revolutionising their media ecology.

We conducted a series of open-ended individual interviews with the subjects primarily in “hang outs” such as street corners or shop fronts, and almost never in their homes, schools or work places. We interacted with and profiled each subject over the course of several weeks and multiple interviews (ranging from 30–90 minutes per interview). Following Tacchi, Slater and Hearn (2005) we focussed on the actual use of, and interaction with, technologies in the wider context of people’s lives and social and cultural structures, which Slater and Tacchi (2003) refer to as “communicative ecologies”. This approach aids two processes: broad understanding of the wider culture, socio-technological structures and communicative ecologies of the research field; and more targeted research aimed at understanding one particular issue or set of issues in the community (Ibid, p. 94). The focus is less on the technologies themselves than on their innovative and creative uses in various combinations and in specific locational contexts. Our initial focus was to observe the processes by which teenagers acquired mobile phones and activated and used Internet on them. From a broad understanding of these behaviours, we narrowed our focus to how the Internet was purchased and expensed for persistent and sustained usage. A number of teenagers offered vivid pictures of how they fit the Internet into their lives, and what they gained as a result of these practices. Many described straightforward sets of functions that the Internet allowed them to carry out, not just as a technical tool but as a social tool: talking to friends, interacting with other people, communicating and chatting with friends and family, listening to music, playing games, watching movies and video clips, and sharing unique experiences fashioned by this new entity called the Internet. We broadly coded observational and interview data and organised them manually into matrices to shed light on specific aspects of mobile Internet access and use. More importantly, we explored how these unfolded in a context bearing financial, technical and infrastructural constraints. Given our overall concern with limited financial affordance for accessing and managing Internet experiences, we focussed on and addressed a) dominant usages of the Internet, (b) the ways expenses are managed to persist with the Internet, c) motivations and literacies shaping the Internet experience, and d) how are these sustained. Our aim is to bring out the cultural practices that youth create and engage in their everyday environment to pursue technology practices.

We highlight strategies teenagers adopt to persist with the Internet − the result of innovations to manage needs within means by staggering costs, scheduling

time and sharing know-how for optimal use. These young Internet users are non-elite, marginally employed and have limited education, which they have struggled to leverage in the downmarket environment of an urban slum. Entertainment usages constitute a significant portion of everyday mobile Internet use, transforming the technology experience of users who have had no previous experience with the Internet. Almost all of them experienced the Internet only on a mobile phone. None had a technical understanding of the Internet but most knew some of the things it could enable them to do. For most, the Internet was a pathway to games, music and videos, driving behaviours to browse, search and identify content on the web.

For users living in urban slums and bottom of the pyramid consumers, there is precious little infrastructure that can uphold 24/7 broadband Internet connectivity. Amidst this scarcity, teenagers use, share and teach the Internet. To do this, they need to expense the Internet in ways that can afford and sustain its persistent use. Kulbeer a 16-year-old high school student from a Hyderabad slum, began using mobiles 4-5 years ago, worked summers assisting a pharmacist and spent an entire month’s salary, around INR 4,000 (US$89), on a second-hand Nokia N-83 to support advanced gaming. Two years ago, for the first time, he used an Internet prepaid coupon worth INR 16 (three cents) with a validity of three days. Users average INR 100 (approximately US$2) for activation and use of the Internet. Almost all of them buy recharge coupons ranging from INR 5 (one cent) to INR 99 (approximately US$2) depending on how much they can afford to spend at the time of purchase.

Facebook walls act as a primary canvas for tagging friends, pushing content on friends’ walls and initiating friendships and chats with persons in far-fl ung parts of the globe. The walls of our participants seem to us a collection of people and material culture they enjoy “gazing” at and accessing at will.

Many deliberate on the size of downloads available for a specific recharge coupon to stagger usage and expenses. Eighteen-year-old Mahesh, who lives in a Chennai slum, goes to high school and works part-time delivering milk in the mornings, has two SIM cards on his phone: one dedicated to Internet browsing and downloads and the other for talk time. Wasim, 17, a high school dropout from a Hyderabad slum who is employed as a contract electrician in a Honda showroom, deliberates on his four SIM cards: Aircel for the Internet; a Vodafone SIM unknown to anyone for making blank calls to tease his friends; TATA DoCoMo for regular calls because of its many offers, such as double talk time and low fares for international calls so that he can talk to his brother in Dubai; and Airtel for a mobile phone he keeps at home. The on-demand Internet is carefully managed, expensed and enjoyed at will and pleasure.

A socio-technical system and an interactional one come into being in the slums of India, transforming novice users of the Internet into expert browsers and content consumers. The street corner club is a public, interactional space accommodating anyone interested in learning and using the Internet. As more youth stepped into the street corner club and adopted the mobile Internet, the more viral the activity became − consisting of regular meetings to chat, learn, discuss and update their knowledge of the mobile Internet. The Internet is no longer peripheral; it is an immersive presence embedded into the lived lives of these teenagers, which thrives through sustained social activity on the street corner. This is where they learn about, get fascinated by, and turn into afficianoados of the mobile Internet. The street corner Internet can be understood as a cultural site, leading to Internet literacy and skill share. Skills are formed, transferred and consequently evolve and congeal around the mobile Internet. The shared “moments” underpin the forging of Internet experiences out of a technology infrastructure that is a messy assemblage of individual and community initiatives. It is this unique mix of the social and the technological that provides a rich and productive terrain for thinking about the sociality of human-technology relations, in this case, in a context of resource constraint. One such space is the shop front of a tiny pharmacy on a street corner, a trouble-shooting paradise for self-proclaimed Internet addicts and generic mobile phone users who gather around experts of Internet use not only to disentangle everyday usability issues but also to learn specific skills.

And then Facebook happened. The mobile Internet rapidly led to Facebook use, growing virally among the slum youth populations. Facebook was a channel that offered multiple affordances seldom available in the lived social reality of our users, be it exploring heterosexual romantic possibilities such as chatting or dating; pushing the boundaries of a limited communication repertoire; acquiring digital literacies, including netiquette; or gaining a toehold in global communities and citizenship. For these youth, Facebook is a path to global modernity, catapulting them away from their downmarket neighbourhoods. One of the most compelling reasons for boys from this sub-stratum in India to be on Facebook is to befriend young women who are culturally unapproachable off-line for dating or even striking casual conversations. Many of our users have transformed into content aggregators, not only entertaining their women friends but acquiring an elevated status on their timelines. They acquire a voice through their posts, which they copy and paste from English language posts appearing on their Facebook feeds, through the themes of their timeline curated content and through their pattern of likes. Through these means, users develop a voice to express and shape a digital persona. When they do build close

friendships with men and women, they maintain them almost every day. Facebook walls act as a primary canvas for tagging friends, pushing content on friends’ walls and initiating friendships and chats with persons in far-flung parts of the globe. The walls of our participants seem to us a collection of people and material culture they enjoy “gazing” at and accessing at will. These youth want to be associated with these images as well as to use Facebook as a space to collect and store content for easy access. With little access to personal computers or broadband, these activities support the idea of Facebook as a spatial repository − a repository where assemblages of “self,” primarily in the form of images, are stored and eventually contribute to a process of identity cultivation signalling the acquisition of material aspirations, dreamy romance and a suave urbane persona.

Behaviours on Facebook strongly suggest friending aspirationally, outside of local contextual affordances, especially of young women of a higher class and in international locations. Not only is social media familiarising these aspirations, but it is offering a new materiality to view and articulate a global aesthetic and life chances in unaccustomed ways; Facebook opens a window to something that was previously a distant mirage.

This possibility of the Internet transforming into a content platform for opportunistic and nonelite teenagers is also an unfolding of a particular form and context of technology access and affordability. Included in this effort was a relative sense of freedom to use the Internet as dictated by desire, motivation and the skills to “work around” limited means and resources. Access, affordability and market pricing are the revolutionising impacts of wireless technologies. We see low-income youth take enthusiastically to the mobile Internet and this essay has sought to explain some of the underlying motivations in this uptake, motivations beyond the utilitarian or functional. This study presents a story about crafting the Internet, anchored in a low-cost but ubiquitous access channel in the developing world. We discovered entertainment as a critical area of technology infusion, leading to the discovery of new skills and abilities, offering a space to experiment with technology, and having the valuable social effects of binding people and creating an informal technology hub.

*This essay is based on a longer paper, “Mental Kartha Hai or It’s Blowing my Mind: Evolution of the Mobile Internet in an Indian Slum,” published in the proceedings of The Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference, 2011.

Further Reading

Boyd, Danah (2006). “Why Youth (Heart) Social Network Sites: The Role of Networked Publics

In Teenage Social Life,” in MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Learning – Youth, Identity, and Digital Media Volume (ed. David Buckingham). (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), pp. 119-142.

Castells, M, M Fernandez-Ardevol, J Qiu, and A Sey (2007). Mobile Communication and Society: A Global Perspective (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Giddens, Anthony (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Cambridge: Polity Press).

Heeks, Richard (2002). “Failure, Success and Improvisation of Information Systems Projects in Developing Countries,” Development Informatics Working Paper No. 11, Manchester University, UK.

Ito, Mizuko et al. (2009). Hanging Out, Messing Around, Geeking Out: Living and Learning with New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Livingstone, Sonia (2002). Young People and New Media (London: Sage).

Livingstone, Sonia (2008). “Taking Risky Opportunities in Youthful Content Creation: Teenagers’ Use of Social Networking Sites for Intimacy, Privacy and Self-expression”, New Media – Society, 10(3): 393-411.

May, Harvey and Gregory Hearn (2005). “The Mobile Phone as Media”, International Journal of Cultural Studies, 8(2): 195-211.

Rangaswamy, Nimmi and Edward Cutrell (2012). “Resourceful Networks: Notes from a Mobile Social Networking Platform in India”, Pacific Affairs, September, 85(3).

Rangaswamy, N and S Yamsani (2011) “Mental Kartha Hai or It’s Blowing my Mind: Evolution of the Mobile Internet in an Indian Slum”, The Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference EPIC, September 18-21, Boulder, Colorado.

Tacchi, J, D Slater and G Hearn (2003). Ethnographic Action Research Handbook (New Delhi: UNESCO).

Slater, D and J Tacchi (2003). “Moderniteit in Opbouw” (“Modernity under Construction”), in Digitaal Contact (eds. J de Kloet, G Kuipers and S Kuik) (Amsterdam: Amsterdams Sociologisch Tijdschrift), pp. 205–22.

Tacchi, Jo (2004). “Researching Creative Applications of New Information and Communication Technologies”, International Journal of Cultural Studies, 7(1): 91–103.