A spurt in activity in the renewable energy sector reveals the shifting importance of the sector in India’s energy supply mix. However, a key constraint in developing the sector is the issue of access to the required finance and scalability of the investments. In a comparative assessment of the impact on financing costs in the renewable energy sector, Professor Gireesh Shrimali outlines measures to improve India’s renewable energy financing challenge.

Introduction – Financing Costs Increase the Overall Cost

As India wrestles with the historic challenge of providing sufficient electricity for its growing population and booming economy, the national government is pursuing another equally difficult and impressive goal — markedly expanding the share of renewable sources in its energy supply mix.

The government has embarked upon an ambitious plan, Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission, to build 20,000 MW of solar power nationwide by 2022 (MNRE, 2009) and is planning for a similar wind mission to have a generating capacity of 100 GW by 2022 (Economic Times, 2014). This flurry of activity demonstrates the seriousness of India’s intentions. But the scale of these ambitions, and the financial resources required, raise many questions regarding the adequacy of the investment to reach these goals, and the efficacy of that investment in reaching the most suitable projects.

Of course, the challenges of the renewable energy sector cannot be completely divorced from India’s overall infrastructure financing challenges. According to the Planning Commission of India, the total investment in infrastructure is required to be over USD 1 trillion during the 12th Five Year Plan period (Planning Commission, 2011). However, the Indian government estimates a USD 300 billion gap in the targeted infrastructure investments, largely due to the lack of long-term finance (Infrastructure Investor, 2010).

A variety of investors finance renewable energy projects in India, including institutions, banks, and registered companies. Return expectations of the investors vary according to the sources of their funds and the risk attached to specific projects. During 2006-09, India’s annual total renewable energy investment remained between USD 4 billion and USD 5 billion. Investment has rose rapidly since then, from USD 4.2 billion in 2009 to USD 12.3 billion in 2011 (Frankfurt School, 2012).

During 2006-09, India’s annual total renewable energy investment remained between USD 4 billion and USD 5 billion. Investment has rose rapidly since then, from USD 4.2 billion in 2009 to USD 12.3 billion in 2011.

While India has some significant cost advantages in terms of lower labour and construction costs, the delivered cost of renewable energy – also known as levelised cost (the average cost of electricity over the life of a project factoring in the return required on investments) – can be as high or more in India compared with the United States (US) due to high financing costs. In comparison to conventional power generation sources such as coal or gas, renewable energy is characterised by a relatively high initial investment, followed by low variable costs. Since a much greater share of the levelised cost of energy is determined by the initial investment, higher financing costs have a disproportionate impact on renewable energy.

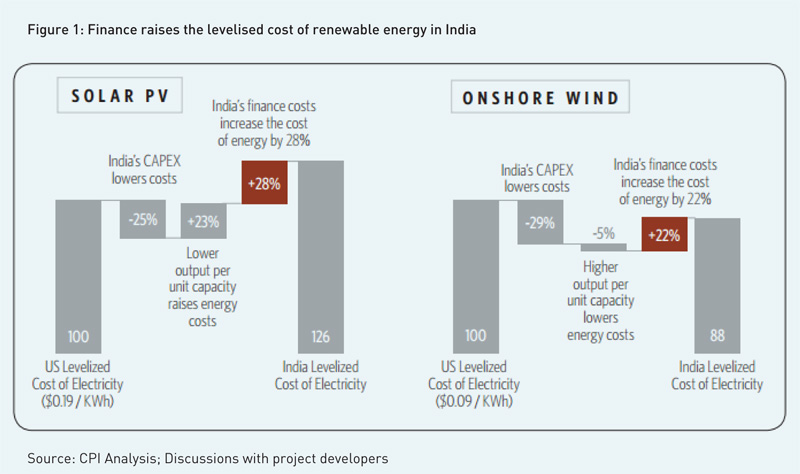

To assess the impact of financing costs, we compare two typical large-scale installations in the U.S. against similar projects in India to quantify the sources of differences in the levelised costs. We found that financing costs add up to 22-28% to the levelized costs of renewable energy in India (Figure 1).

In the case of solar, the impact of capital costs in India resulted in a levelised cost 25% lower than in the US. However, most of this cost advantage was eliminated by the lower expected output per MW, which was likely the result of lower plant utilisation factor. With these two factors offsetting each other, the Indian solar photovoltaic (PV) facility was nevertheless 26% more expensive due entirely to the higher return requirements for investors in India, that is, the more expensive cost of financing the project.

The two wind projects depict a similar story, although the wind project in India is still cheaper, despite the higher financing costs. While these projects do not represent all US or Indian renewable projects, and rapid changes to cost and performance could lead to constantly changing figures, the comparison itself is indicative of the substantial impact of financing costs on renewable energy in India. The key takeaway is that the renewable projects could be much cheaper if not for the higher financing costs.

Costs and Terms of Equity and Debt – Impact on Financing Costs

Conditions for renewable energy finance are quite different for investors in the debt markets and those in the equity markets. Generally speaking, debt investors are more conservative, accepting lower returns in exchange for lower risk. As such, their primary concern is that downsides are limited; that is, that the project does not fail. Equity investors are willing to take more risk in exchange for higher returns, and therefore focus equally on risk and the prospects of a project performing even better than expected.

Under most circumstances, a project will be least expensive when it is funded by a mix of debt and equity, either at the project level or at the corporate level. Renewable energy financing can become costly when either debt or equity investors demand too high a return or when either is simply unavailable. In India, the differences between debt and equity are particularly striking. In general, we find that equity appears to be readily available at a reasonable cost, while debt is both limited and expensive.

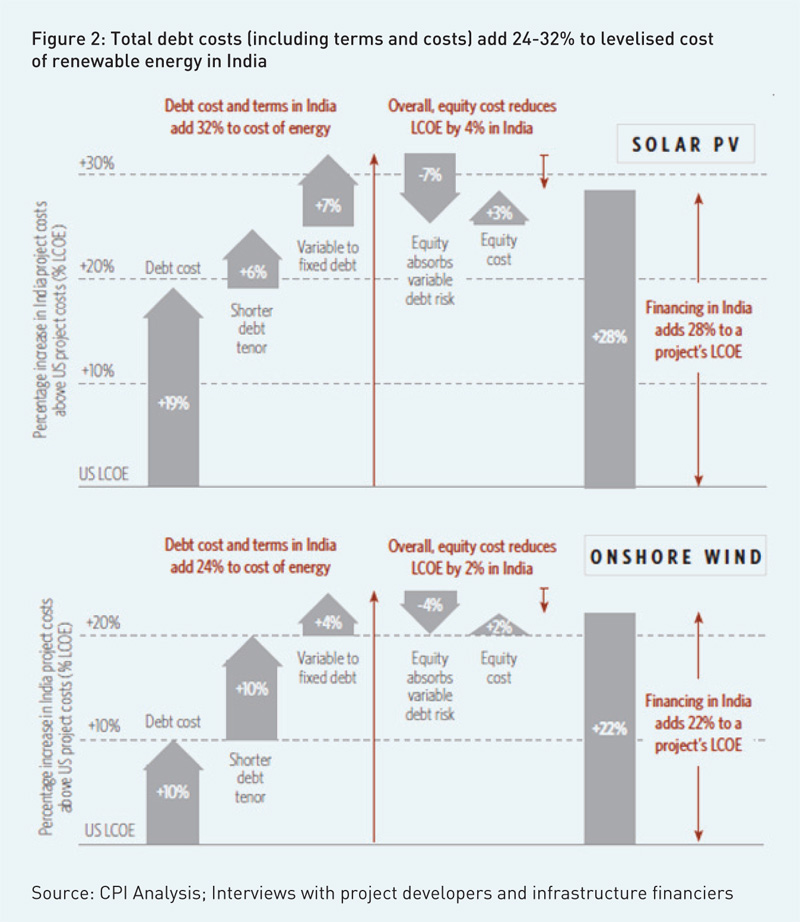

To understand the impact of costs and terms of debt and equity on the levelised cost of renewable energy in India, we examined the same projects in the US and India (Figure 1) with usually available terms and conditions for debt and equity. We found that many factors such as the cost of debt, the tenor of debt, variable or fixed debt rate, extra risk for equity investors if debt rate is variable, and the cost of equity; influence the total finance cost.

Our analysis indicates that the financing costs add 28% and 22% to the levelised cost of solar PV and wind projects, respectively, in India (Figure 2). Our key findings include:

•In the case of the solar PV projects, the higher interest rate on the debt alone added 19% to the levelised cost, while it added 10% to the wind project.

•Indian debt tenors are typically much shorter than in the US or Europe. Overall, we found the shorter debt tenors added between 3% and 10% to the levelised cost, by forcing more rapid amortisation of the loan, and therefore reducing the effective leverage over the life of the project.

•Despite being more costly, the debt terms in India are less attractive, particularly the variable interest rate of most debt in India. The variable interest rate cost added approximately 7% to the finance cost of solar PV and 4% to the levelised cost of wind on a comparable basis.

•The corollary to the lower value of the variable rate debt is that equity is actually taking on more risk. While we have no accurate way of measuring the cost of the additional risk assumed by the equity investor, we assume that the risk they take on is equal to the value of the US variable-to-fixed rate swap. The result is an exact offset between debt and equity.

•The cost of equity in India is only slightly higher than in the US or Europe, depending on the technology, despite the higher underlying country risks. The slightly higher Returns on Equity (ROE) added only 3% and 2% respectively to the total cost of financing the solar and wind project.

•It is significant that, on an adjusted basis, project ROEs in India are below those in the US. This implies that equity investors are buying into the market and accepting below rational returns for strategic reasons — thus suggesting that ROEs may rise once the market matures.

We found that many factors such as the cost of debt, the tenor of debt, variable or fixed debt rate, extra risk for equity investors if debt rate is variable, and the cost of equity; influence the total finance cost. Our analysis indicates that the financing costs add 28% and 22% to the levelised cost of solar PV and wind projects, respectively, in India.

India’s Achilles Heel – High Cost of Debt

As is typical for rapidly developing countries, growth in India comes with a need for investment in new infrastructure, creating competition to raise debt; and general inflationary pressures that need to be controlled through higher interest rates. As a result, benchmark interest rates in India are significantly higher than in developed countries.

Indian interest rates are now higher than the rates in other developing countries such as, China and Indonesia, while slightly lower than Brazil. The difference between benchmark interest rates in India and the US and Europe account for nearly all of the 5-7% difference in debt costs between renewable energy projects, even when adjusted for the fixed rate premium (2% +) that the US and European debt should be given.

We also observed that the short debt tenors in India play a significant part in keeping the costs high compared to developed nations such as the US. Our analysis indicates that an increase of debt tenor by seven years would lead to a decrease of 6% in the levelised cost of a generic solar power project. But long-term debt is not easily available in India due to various reasons including, over-dependence on commercial banks for infrastructure lending, the corporate bond market remaining under-developed and due to the reduction of the role of development financial institutions subsequent to the economic reforms of 1991.

In addition, in India, loans commonly have variable interest rates rather than fixed interest rates as banks usually lend for short term and due to the near-absence of bond markets. Long-term hedging instruments — term-swaps and bonds — are typically unavailable due to immature financial markets and risks related to a growing economy. Variable rate debt makes cash flows to equity holders (which include project cash flows minus the interest payments to debt holders) less certain as they are subject to changing interest expenses.

With regard to the availability of debt in India, we heard conflicting views. In general, larger companies with good relationships with banks have access to debt. Superior projects also seem to have access. However, marginal projects with smaller, unconnected developers might find it more difficult. Our conversations with project developers indicate that access to debt will likely become even more difficult in the long term due to: banks reaching their prudential lending limits, lack of understanding of renewable energy technologies among the lenders, and regulatory caps on foreign loans.

The availability of finance also depends on the type of technology. Wind is typically easily funded, given its track record and increasing competitiveness. On the other hand, solar is still new; so many banks are cautious and are adopting an ‘invest-a-little’ and then ‘wait-and-see’ strategy. As a result, projects financed solely by equity are more common in the solar PV space. The question that arises is whether solar PV will mature fast enough such that banks will lend to the projects before developers exhaust their patience, strategic intent and financial reserves.

Also, availability of debt varies from state to state depending on the financial health of state-owned power distribution companies, which typically purchase the power generated from renewable energy producers. According to banks, it has become harder to provide loans in several states due to the risk associated with the poor finances of the distribution companies. The state of Tamil Nadu is noteworthy in this aspect: though Tamil Nadu has the highest wind-energy capacity in India, banks are now refusing to provide debt to new wind-power projects, given the poor health of Tamil Nadu’s distribution companies.

The availability of finance also depends on the type of technology. Wind is typically easily funded, given its track record and increasing competitiveness. On the other hand, solar is still new; so many banks are cautious and are adopting an ‘invest-a-little’ and then ‘wait-and-see’ strategy.

Equity – Ample Availability, But Can it Last?

Under normal circumstances expected return on equity should be higher than the cost of debt outside exceptional circumstances. Equity has decidedly more risk, and thus should attract higher returns. The role of debt, in fact, is normally to concentrate the risks to the equity holder and therefore enhance equity returns. Another role is to replace the equity capital of the developer so that they can recycle the money into the next project.

The spread between equity costs and debt costs represents the allocation of risks and returns between debt and equity. While for wind projects we see healthy spreads of 4-7%, the spreads for solar appear to be low in the range of 0-3%. At these return levels, equity investors shouldn’t be interested in solar projects at all. However, some equity investors might have invested, accepting lower returns in the short term to gain advantage in the long run. Some other investors could have invested expecting a fall in solar panel prices during the construction period and a reduction in interest rates during the lifetime of the project.

Equity induces developers to take on and develop a project and eventually, negotiate power purchase agreements (PPA) and loans. Discussions with stakeholders revealed that the availability of equity from both domestic and foreign sources is comparatively better than the availability of debt. In fact, our discussions revealed that international equity might be more readily available than domestic equity.

However, our discussions also revealed that the lack of availability of debt to refinance a project may actually force equity to be kept in a project for too long, and hence restrict the equity available for recycling and starting new projects.

Easing the Renewable Energy Financing Challenge

The Electricity Act of 2003 transformed the power sector in India by driving changes such as deregulating power generation, opening access in transmission, and allowing the state electricity regulatory commissions to fix the level of renewable energy procurement. The National Electricity Policy (2005) and Tariff Policy (2006) followed, with the goal of increasing the share of renewable energy in the total energy supply mix.

Currently, the Indian government supports the development of renewable energy through a variety of incentives and mandates. The support initiatives include – preferential tariffs, accelerated depreciation, generation-based incentive, income tax exemption, renewable energy certificates, and other benefits such as concessional rates of excise and custom duties.

However, we observe that renewable energy financing cannot be improved through renewable energy policy alone. The single biggest issue lies with the general Indian financial markets conditions. We recommend that the government focuses on solving the problems of the general financial markets, which include developing the corporate bond market, controlling inflation, and relaxing regulations governing foreign borrowings in the short-term.

In the long run, the government should focus on fine-tuning the existing support mechanisms for renewable energy such as the renewable energy certificate markets and fix problems associated with state-level policy issues. To reach the ambitious national-level renewable energy targets, the Government of India launched a market-based mechanism in 2011 in the form of Renewable Energy Certificates (REC). Under this mechanism, certificates are issued to renewable energy power generators, which can be sold later in recognised power exchanges. RECs have been widely touted by many analysts as the solution to drive investment into renewable energy generation.

However, our examination of the actual performance of REC market trading shows that the current number of certificates issued is less than 4% of the technical REC demand potential, indicating that the full potential of REC markets is far from being realised. Our analysis (CPI, 2012) clearly indicates that RECs are not considered viable financial instruments by investors, and several changes are needed if the REC mechanism is to deliver its intended results.

The REC mechanism, as currently structured and executed, is unlikely to achieve most of the government’s objectives. In particular, to create a stable market for RECs and reduce demand uncertainty, stricter compliance laws and enforcement of state-level Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPO) will be required. An RPO is a state-level regulatory mandate that requires obligated entities that include distribution companies, captive consumers, and open access consumers, to procure a certain percentage of their electricity requirement from renewable energy sources. The entities can meet the RPO through generating renewable power themselves, by buying from other renewable power generators, or by purchasing REC certificates. Further, to make RECs viable financial instruments, the government will need to not only declare state-level, long-term targets along with their annual targets but also enable well-functioning secondary markets.

The success of REC mechanism is intertwined with state-level policy issue of lack of stringent implementation of RPO especially for state-owned distribution companies. In addition, poor financial health of the majority of the state-owned distribution companies heightens the risk of lending to renewable project developers, who signed power off take agreements with these companies. The government should focus on improving the financial health of state distribution companies and strive for effective implementation of the REC mechanism.

Currently, the Indian government supports the development of renewable energy through a variety of incentives and mandates. The support initiatives include – preferential tariffs, accelerated depreciation, generation-based incentive, income tax exemption, renewable energy certificates, and other benefits such as concessional rates of excise and custom duties.

Policy Support – International Comparisons

Beyond India lies a wealth of renewable energy policy experience in other countries, including the US, Europe, China, and Brazil. Beyond the implications for levelised cost, we have used our models to evaluate the impact of different policy instruments on overall project financing costs in the US, Europe and India. While our results point to some lessons that can be learned from these countries, general market conditions weaken their effect in India. Given that, we explore whether other important lessons could be drawn from other rapidly emerging countries such as China and Brazil.

To evaluate how policies impact the levelised cost of renewable energy, we examined the policies based on their characteristics of how they affect investor cash flows or perceptions. We measured the impact of these policies through six different pathways for representative projects in the US, Europe, and India. The pathways include: duration of revenue support, revenue certainty, risk perceptions, completion certainty and cost certainty.

Our analysis indicated that in the US and Europe, extending the length of a support policy could lower levelised costs. We also found that mechanisms such as feed-in tariffs offering constant, stable prices could also lower levelised costs, as could mechanisms with variable support, but appropriate and well-designed price floors, such as feed-in premier with floor prices. Meanwhile, cost and completion certainty could be solved mainly through already commercially available contracting arrangements.

For India, differences between the policy impact pathways are smaller. This is because one important mechanism for reducing financing costs is reducing risks to allow increased debt and project leverage. With debt costs so high in India, the value of leverage is lower. Secondly, some of the commercial contract mechanisms to reduce construction risk may not be as reliable in India.

More significantly, all of the policy pathways are dwarfed by the potential impact of reducing debt costs. A key take away is that the higher interest rates, and shorter debt tenors, may reduce some of the effectiveness of developed world renewable policies. For Indian policy makers, a key lesson is that they should explore methods of reducing the cost of debt to renewable energy projects. Furthermore, they might look to countries with similar growth and interest rate environments, and particularly Brazil and China.

Both China and Brazil adopted the method of providing concessional finance to reduce the levelised cost of renewable energy. While China’s renewable energy capacity is largely built by state-owned companies that have access to low-cost government funding and guarantees, Brazil provides concessional finance to renewable energy project developers through its national development bank, BNDES. In both the cases, the focus is on reducing the cost of debt as these countries face similar problems of high inflation and interest rates as is the case in India.

Conclusions

The main conclusions of our analysis can be summarised as below:

•The high cost of debt, that is, high interest rates, is the most pressing problem facing renewable energy financing in India and has significant impact on the levelised costs. As of now, neither the cost nor the availability of equity is a major problem, but this could change, particularly if debt becomes less available.

•General Indian financial market conditions are the main cause of high interest rates for renewable energy. Growth, high inflation and country risks all contribute. A shallow bond market and regulatory restrictions on capital flows also adds to the problem. Continued high government borrowing keeps the risk-free rate elevated.

•Regulation and the structure of the Indian power sector also raise significant issues. State-level policies – including the financial weakness of the state electricity boards – increase project risk. National policies designed to weave state policies together do not adequately reflect the realities of financial markets or state-level risks.

•Differences in national financial markets impact renewable energy policy design and effectiveness. Lessons learned from, and policies developed by, developed economies may not be particularly useful given these differences in financial markets.

•Other developing countries have bridged the financing gap in unorthodox but successful ways. Brazil’s BNDES is an especially promising example that deserves further study and consideration by Indian policymakers.

Further Reading

You can read the full report: “Meeting India’s Renewable Energy Targets: The Financing Challenge”, Nelson, D, G Shrimali, C Konda, S Goel and R Kumar, CPI-ISB Report, December 2012 here: http://climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/meeting-indias-renewable-energy-targets-the-financing-challenge/

CPI (2012), G Shrimali, S Tirumalachetty and D Nelson, “Falling Short, An Evaluation of the Indian Renewable Certificate Market”, http://climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/falling-short-an-evaluation-of-the-indian-renewable-certificate-market/ (Accessed in December 2012)

Economic Times, 2014, First National Wind Energy Mission to begin by mid-2014, http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-01-08/news/45991703_1_wind-sector-generation-based-incentive-wind-power (Accessed in May 2014)

Frankfurt School (2012), Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2012, http://fs-unep-centre.org/sites/default/files/publications/globaltrendsreport2012.pdf (Accessed in October 2012)

MNRE (2009), Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission, http://www.mnre.gov.in/file-manager/UserFiles/mission_document_JNNSM.pdf (Accessed in April 2012)

Planning Commission (2011), An Approach to the Twelfth Five Year Plan, Government of India.

Infrastructure Investor (2010), India estimates a USD 300 billion infrastructure funding gap, Infrastructure Investor.