In this paper, Professor Rohit Prasad contrasts the regulatory approaches in traditional media and the Internet and argues that, a new approach is required in the increasingly converging media world. This regulatory approach must synthesise diversity of media content, ie, media plurality and the free play of consumer choice and service innovation on the internet, ie, net neutrality and promote community-generated content.

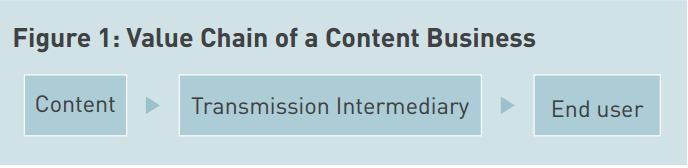

Traditional media and the Internet are both content businesses, although the Internet is additionally an applications business. In this paper we deal with the regulation of news generated on television and on the Internet. We assume the aim of media regulation is plurality, i.e., media should reflect a diversity of opinion, generated by a broad spectrum of citizens and shared widely with relevant sectors of the population. We start by delineating the value chain of a generic content business, present the variations in the case of traditional media and the Internet, identify the different regulatory approaches used in each and suggest a way forward based on a convergence of traditional and new media.

Value Chain of a Content Business

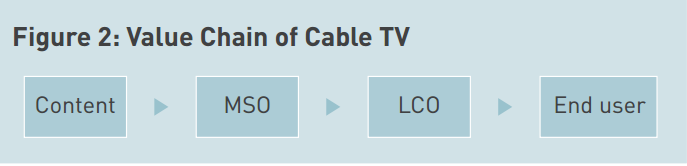

Every content business consists of a content creation layer, a content transmission layer (intermediary) and an end user. This generic value chain acquires different hues in the context of the different forms of TV broadcasting: terrestrial, cable, direct-to-home (DTH), broadband and wireless. In terrestrial broadcasting and DTH, signals are sent directly to the user’s television and are unscrambled using a set top box. In cable TV, signals are sent to a multi-service operator (MSO) who unscrambles them and sends them to local cable operators (LCOs), who send them forward to consumers. In broadband, telecom operators install optic fiber cables to users’ homes and offer a “triple- play” service of voice, data and TV connectivity. In wireless, telecom operators provide high-speed Internet connectivity, which can be used to wirelessly access TV programming being streamed on the Internet. The value chain in the case of cable TV, still the most popular mode of watching TV, is shown in Figure 2:

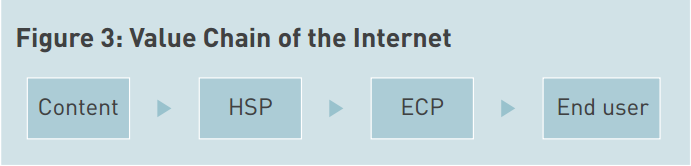

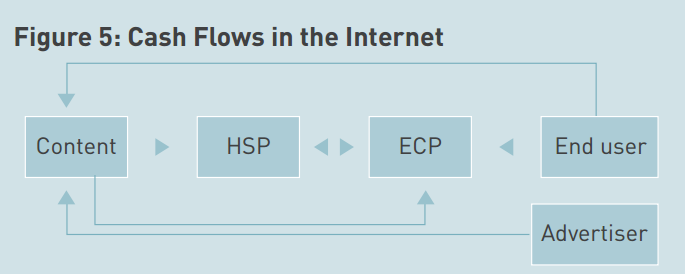

In the case of the Internet, the content created by the content provider is hosted by a hosting service provider (HSP) who has an agreement with an end user connectivity provider (ECP) to reach the end user. The end user accesses the content on a device such as a mobile phone or a tablet. The value chain in the case of the Internet is shown in Figure 3 (the device vendor is left out for ease of exposition):

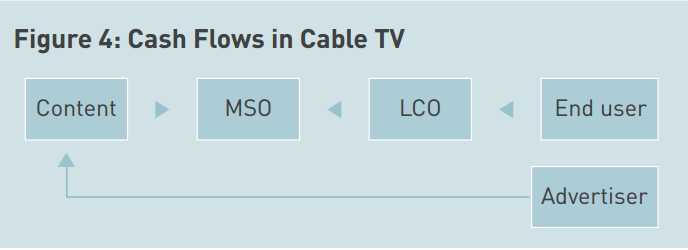

Two very important and interrelated factors determining the nature of the value chain are the manner in which different entities in the value chain are compensated and their role in deciding the content that the user consumes.

In the cable TV value chain, prior to digitisation, the content provider paid the MSO, the end user paid the LCO and the LCO paid the MSO. The advertisers paid the content provider. The LCO created various packages of programmes, based on what they could afford to buy from the MSO, and sold them to the end user. The MSO and LCO had the freedom not to carry certain programmes on their network in order to conserve scarce capacity, or, conversely, to charge a premium for pushing certain content providers on basic bands. After digitisation, it has become easier for the MSO to track the programmes the end user watches. Hence, the LCO cannot underreport revenues. Part of the revenues from the end user can also flow to the broadcaster.

On the Internet, the content provider pays the HSP, and the end user pays the ECP. The advertiser pays the content provider. The HSP and the ECP usually have a “bill and keep” arrangement, under which they provide free services to each other and allow each other to charge content providers and end users respectively. A controversial issue relates to whether ECPs can charge content providers and on the measures they can take to conserve scarce capacity on their networks.

Regulating the Value Chain in Media and the Internet

The description of the value chain illustrates key aspects of the regulatory approach in traditional media and the Internet. In traditional media, the aim is to curtail the market power of the content providers, in order to ensure that a wide range of opinion is available to the viewer. The market power of the intermediary is not the focus of the regulatory scanner.

The broadcaster must stand ready to provide its content to any intermediary. It is not mandatory, in many cases, for the intermediary to carry the content. For instance, the Indian Broadcasting and Cable Services Interconnection Regulation 2004 has a must-provide clause for broadcasters but no must-carry clause for intermediaries (ASCI 2009). With digitisation, there is perceived to be no capacity crunch for the intermediary, and hence, the intermediary cannot refuse to carry the content of any broadcaster. However, it is considered acceptable for the intermediary to create a portfolio of plans from which viewers choose. The accretion of market power resulting from vertical integration between the content creator and the distributor is controlled through limits on cross-holding – for instance, in India, a broadcaster cannot own more than 20% of an MSO (TRAI 2009).

Regulation of the Internet, while a relatively new phenomenon compared to traditional media, takes a different approach to regulating the content provider and the intermediary. One of the influential schools of thought in this area is net neutrality. The aim of net neutrality is to let the content and applications that emerge on the Internet be decided entirely by the interplay of consumer choice and service innovation. It seeks to circumscribe the role of the intermediaries between the content provider and the end user, especially that of the ECP. In the case of fixed line access, the ECP may be a natural monopoly, and in the case of wireless access, an oligopoly with a measure of market power. This movement is based on the “end- to-end” design principle (Saltzer et al 1984). As per this principle, the control and intelligence functions must reside largely with users at the “edges” of the network (content provider and end user), rather than in the core of the network itself (intermediary). It is believed that the regime of net neutrality has driven the amazing innovation witnessed on the Internet.

Net neutrality proponents are mindful of the fact that vertical integration between an intermediary and a content provider can also militate against the end- to-end design principle. Hence they look askance at discriminatory behaviour arising in the context of vertically integrated entities. The ECP cannot refuse to carry any content or application based on the amount of bandwidth required or other technical characteristics of the transmission (such as required mouth to ear delay). Further, it cannot charge content providers and, in some extreme versions of net neutrality, cannot use traffic management techniques to manage network flow. Investments required to carry content are to be recovered from end users based on non-discriminatory criteria like volume of download. Content providers are required to pay their HSP who has a bill and keep arrangement with the ECP.

Regulation of the Internet, while a relatively new phenomenon compared to traditional media, takes a different approach to regulating the content provider and the intermediary. One of the influential schools of thought in this area is net neutrality. The aim of net neutrality is to let the content and applications that emerge on the Internet be decided entirely by the interplay of consumer choice and service innovation.

The rules on net neutrality announced in the United States (US) in 2011 require transparency in network management by intermediaries and prohibit blocking of content or applications by fixed line broadband service providers (who do not have capacity constraints) and discrimination by mobile service providers against applications that compete with their own offerings, e.g. Skype. Netherlands is the first country to apply net neutrality in full for both landline and mobile operators.

Net Neutrality versus Media Plurality

The discourses on net neutrality and media plurality are interlinked because both industries are content- based and therefore, share common principles. In economies like India, the growth of the Internet is at a nascent stage but is gaining in importance. As the Internet becomes a channel for the distribution of all kinds of content, including news, one cannot have media plurality unless there is a reasonable environment of innovation and openness on the Internet. Similarly, injunctions on net neutrality would be diluted unless the traditional channels of media also deliver pluralistic viewpoints.

Given the absence of any discussion related to the content provider or significant elements of the value chain such as device manufacturers, the implicit assumption of the net neutrality approach is that market power resides in the intermediary but not in the content provider or the device manufacturer. Alternatively, the premise may be that such market power may exist, but barriers to entry are low and that inefficiency or lack of innovation will be punished by new entrants. Inherent to this reasoning is the hypothesis that the end user, unimpeded by a market power exercising intermediary, is qualified to assess the value of different content and application offerings. In other words, there is no asymmetric information between the user and the content provider. The assumption in the media plurality discourse on the other hand is that market power lies with the content provider and not the intermediary. A further assumption is that either consumers are not always capable of making out “good” from “bad” content or, even if they can that the barriers to entry for new broadcasters would prevent media plurality.

The differing approaches of media plurality and net neutrality can partly be explained by the different histories of the traditional media industry and the Internet. The history of the regulation of traditional media goes back to the early years of the 20th century, with roots in print media and terrestrial TV. The role of the intermediary in the deliver y of print news and terrestrial TV was negligible. Perhaps due to this reason, not much attention was paid to monitoring the intermediary, even after the intermediary became a vital cog in the value chain with the coming of cable TV, broadband and DTH.

On the other hand, at the time of the advent of the Internet, the most entrenched entities in the landscape were the intermediaries who provided the dial-up connection – the telephone companies. Telephone companies had traditionally been under the regulator y scanner and thus, almost by default, drew attention in the Internet industry as well. Preventing them from taking advantage of their position as a bottleneck monopoly, i.e., the sole conduit to the end user, was seen as the primary aim of regulation.

Convergence of Regulatory Approaches

The stances in both the traditional media and the Internet need to be broadened. As regards the assumptions of net neutrality, certain content/ application providers, for instance Google, have significant market power that the end user may not always be able to sense. For instance, search returns may be taken as having objective truth value, while in fact, they may only reflect the wisdom of one particular algorithm for choosing relevant websites.

There are high barriers to entry on the Internet, even without marauding intermediaries. Setting up an Internet Protocol television (IPTV) channel requires significant investment. Further, entities other than content providers and intermediaries, such as device manufacturers, have significant market power. Apple adopts a “walled garden” approach whereby it provides a seamless end-to-end user experience including content, apps and connectivity. Thus, it becomes an important filter for the kind of content its loyal customers consume.

In economies such as India, the growth of the Internet is at a nascent stage but is gaining in importance. As the Internet becomes a channel for the distribution of all kinds of content, including news, one cannot have media plurality unless there is a reasonable environment of innovation and openness on the Internet.

The assumptions of media plurality are also questionable. Some intermediaries may have significant market power that could rival that of the broadcasters. The recent spat over carriage fees between Hathaway, an MSO, and IndiaCast Media Distribution, a content provider (IndianTelevision.com Team 2012), shows that intermediaries are no pushovers. Lack of fair, pluralistic reporting may draw the disfavour of consumers and not need regulator y policing. With the right relaxation of regulations, barriers to entry in the TV news industry could be lowered, so that incumbents feel competitive heat from potential entrants irrespective of their market shares.

Promote Contestability

In certain contexts, modern regulatory economics emphasises contestability as a possible regulatory target rather than even and widely distributed market shares (Baumol 1982). The philosophy of a contestability- led regulatory approach is to make barriers to entry and exit low so that incumbents are forced to strive for better quality and lower prices, no matter how concentrated the industry may be. By its very nature, the media industry, especially TV, requires high upfront investment. However, competition to TV news comes not merely from other news channels butalso from media like radio and print. Contestability in the news industry as a whole can be influenced by measures that include allowing FM radio channels to transmit news, and rationalising taxes and licence fees.

Limiting cross-media ownership is preferable to controlling shares within a single media as the economies of scale (and bandwagon effects for viewers) within a particular media are greater than the economies of scope across media. Some countries like the UK follow the “two in three” rule whereby an entity can only be present in two out of the three media channels of TV, radio and print.

A very important counterpoint to corporate media can be the state-sponsored TV station. However, it is usually seen as a mouthpiece of the government. The allocation of public money to create a truly independent news channel can be a source of great public good. Other alternatives include a public broadcasting service supported by user contributions.

There is no theoretical argument or empirical evidence on the correlation of media plurality and plurality of media ownership. Indian data on market shares, especially in television, are not reliable. In such a situation, monitoring the competitiveness of the media industry through traditional economic measures such as the Herfindahl Hirschfield Index (HHI) should be done with care.

Avoid Paternalism

Curtailing a media company that has grown on the basis of popularity with readers may not be appropriate, and may even be regarded as an infringement of the right of free expression, unless there is evidence of an unacceptable abuse of market power (vertical integration with a transmission intermediary can certainly facilitate such abuse). A certain degree of lack of plurality may be in alignment with viewer preferences. For example, in Tamil Nadu, public opinion is split between two Dravidian parties, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIDMK), and viewers are perhaps not unduly ruffled by the fact that the Tamil TV channels mostly reflect the opinions of one or the other of the two parties. It may be paternalistic to impose one’s ideal of media plurality on a satisfied viewership.

Look Beyond Corporate Media

The regulator y approach must not restrict itself to media funded and managed by advertising and, to a lower extent, subscription revenues. Such media inherently converges to mainstream points of view – those held by the “median viewer,” the viewer at the centre of the news spectrum, the position containing the maximum number of viewers, or containing viewers who have the maximum ability to pay. This convergence is easily seen in the case of news related to business, with most media adopting a pro-business, pro-market stance, favouring the “hand that feeds them.”

Hence, while attempts to make the corporate media more competitive must continue, the need to go beyond must be kept in mind. An attempt must be made to promote community-generated news through community radio and TV. Progress on community radio has been slow and painful in India. A landmark judgment of the Supreme Court of India of 1995 stated that air waves were public property and must be used for the public good. This was followed by an appropriate policy only in 2006 that allowed a wide swathe of institutions, including NGOs, educational institutions and agricultural universities, to apply for licences (UNESCO 2011). There is still no policy on community TV even though the large cable network in India provides adequate transmission pipes to transmit content.

Further, one must recognise the potential of peer-to-peer user-generated news. The Arab Spring is an example of the power of this phenomenon. The use of the Information Technology (IT) Act to crack down on free expression of views is an example of what not to do.

Transmission: Who Pays?

There is a feeling that the cost of the transmission of content has to be recovered in some way, and hence, one cannot be too puritanical about not charging content providers as the net neutrality school exhorts one to do. Indeed, carriage fees are standard in broadcasting. The service of the transmitter of content is akin to the provider of a road. A toll to prevent congestion is acceptable on a road, so why should it not be the same for a provider of connectivity services? Even if charging the content provider violates the end-to-end design principle, at least the end user can be charged on non-discriminator y grounds like the quantity of viewing time.

It is to be noted here that the toll necessary to prevent congestion and ensure efficiency may not be sufficient to fund the maintenance and upgradation of the transmission network. Under such circumstances, economic theory states that if the toll good has positive spillover effects on the economy, then it can be supported by general budgetary outlays.

The government is already laying an optic fiber network for rural access. It can also support urban access to broadcasting through subsidies or by building its own DTH and cable network.

Transmission intermediaries may want to differentiate themselves from competition by smart traffic management practices and innovative pricing for connectivity, including charges levied on content providers. However, in keeping with the end-to-end design principle, it is better for them to recover their investment from the end-consumer through non- discriminator y usage plans, rather than to actively mediate between the consumer and the content provider. Competition in the content layer and public-private partnership in the transport layer of the network are preferable to overregulation of the content layer and competition in the transport layer.

Conclusion

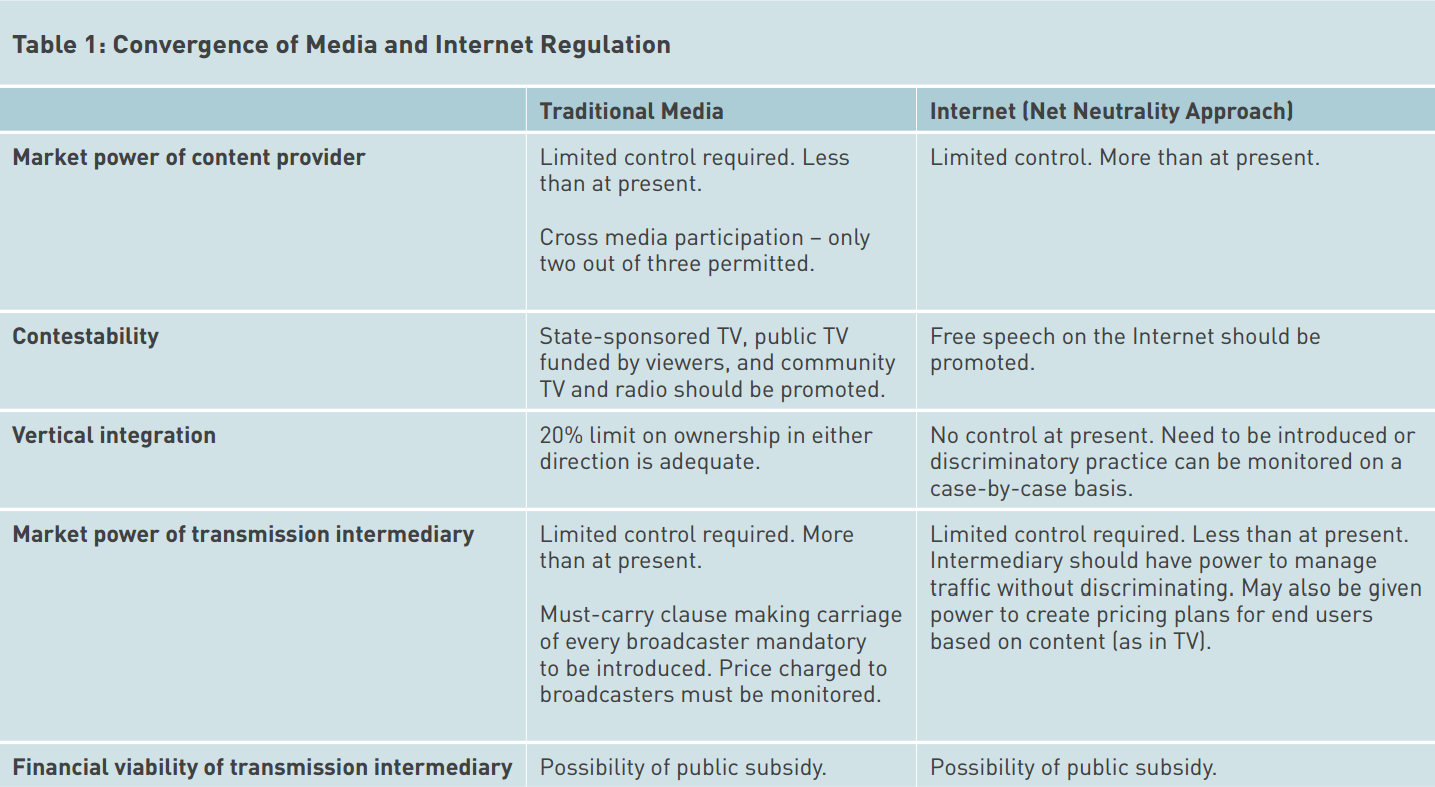

To sum up, the convergence of traditional media and the Internet is on its way. This convergence requires a convergence of regulatory approaches. Given the traditional approaches taken in both media, a synthesis of the net neutrality and the media plurality approaches is the order of the day. The following table highlights some of the key recommendations of this paper. It is time to use the power of technology to make a thousand flowers bloom – in broadcasting as well as on the Internet – and to enhance the power of community-generated media so that the need to police corporate media can be limited.

For further reading

Administrative Staff College of India (ASCI) (2009). “A Study on Cross Media Ownership in India”, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, New Delhi.

Baumol, W (1983). “Contestable Markets: An Uprising in the Theory of Industry Structure”, The American Economic Review, 73(3):1-15.

IndianTelevision.com Team (2012). “DAS Phase II: Indiacast- Hathway-GTPL slugfest on DAS deals”. Accessed on June 5, 2013: http://www.indiantelevision.com/headlines/y2k13/apr/apr49.php Saltzer, J H, D P Reed, and D D Clark (1984). “End-to-End Arguments in System Design”, ACM Transactions on Computer Systems, 2(4): 277– 288.

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) (2009). “Recommendations on Media Ownership”, TRAI, New Delhi. Accessed on May 29, 2013: http://www.trai.gov.in/WriteReadData/ Recommendation/Documents/recom25feb09.pdf

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) (2011). “Ground Realities: Community Radio in India”, UNESCO, New Delhi. Accessed on May 29, 2013: http://maraa.in/ wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Maara_inside-pages.pdf