In 2010 one-fifth of the 287,000 maternal deaths worldwide occurred in India (WHO 2012). Every year over 300,000 new-borns in India die the day they are born accounting for 29.5 percent of global birthday deaths. Primary causes for neonatal deaths are premature birth, low birth weight, neonatal infection, birth asphyxia, trauma, and tetanus. While severe bleeding, infections, high blood pressure, unsafe abortions are primary reasons behind maternal deaths. Curbing these high rates of neonatal and maternal mortality with existing healthcare infrastructure is a key challenge for policy makers.

Access to healthcare facilities, where the expecting mothers are assisted by medical personnel with pre-natal and postnatal healthcare, may improve neonatal and maternal survival. However, demand and supply side factors limit use of maternal health facilities, including financial constraints, lack of knowledge about available services, distance to medical facilities and low quality of services. In 2005, nearly 70 percent of rural women in India delivered their babies at home.1 Cash transfer to low-income households, conditional on the use of particular public services, is a popular tool to increase healthcare utilisation. Apart from financial constraints there are non-monetary reasons for not utilising a medical facility for the first time. These include remote location and unavailability of transportation infrastructure, redundant and long-drawn process and doctor’s ignorance of the expectant mother’s medical history.

A subsidy on healthcare utilisation may allow a first-time user to learn about the characteristics of that product or service, affecting her future demand as well. Latin American countries have used such Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) programmes for a long time to improve school attendance, healthcare utilisation and nutritional support. Bolsa Família in Brazil and Oportunidades (subsequently renamed Progressa) in Mexico are among the most successful ones. Drawing from the success of these programmes, CCTs are increasingly becoming popular among policy makers for tackling low school attendance and preventive healthcare utilisation. By 2011 CCTs had spread to 18 countries in Latin America and covered as many as 129 million beneficiaries. Such programmes are not restricted to developing nations alone. For example New York City implemented Opportunity NYC in 2007 that provided cash incentives to families if a student had 95 percent attendance, parents attended parent-teacher meetings and so on. An evaluation of these programmes found positive effects on the relevant outcomes.

Rigorous evaluations of unconditional cash transfers covering a wide range of programmes, such as non-contributory pension schemes, disability benefits, child allowance, and income support, were also carried. Empirical evidence suggests that unconditional cash transfers reduces child labour, increases schooling, and improves child health and nutrition.

The debate about the relative merit of these two types of programmes has intensified as CCTs have become widely adapted as part of public policy initiatives. Advocates of CCT programmes often argue that underinvestment in education and health is common if families do not readily understand their benefits, which is addressed by the conditions imposed on receipt of welfare scheme. Another advantage of CCT programmes is that the conditions make cash transfers politically feasible to middle- and upper-class voters who are not direct beneficiaries of government transfers. On the other hand the marginal contribution of the conditions added on to cash transfers are not well understood in many countries. Furthermore, verification of the statutory conditions required to receive the benefits may strain the administrative capacities in poorer countries where facilities are less developed than Latin American countries.

The Programme

Janani Surakshya Yojana (JSY or Safe Motherhood Scheme) is a CCT programme in India. It was launched in April 2005 with the objective of improving maternal and neonatal health by promoting delivery in institutional settings (healthcare facilities) among pregnant women. The programme provided cash incentives to pregnant women and health workers to facilitate birth in a public or private health facility. While the JSY programme is implemented all over India, it gave special emphasis to ten low-performing states that had low levels of institutional delivery.2

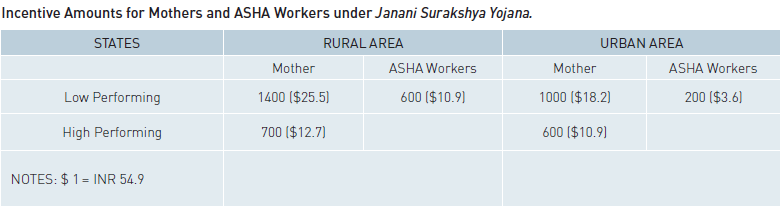

Eligibility for cash assistance varied depending upon the state, caste, and economic status of the pregnant woman. In low-performing states all pregnant women delivering in government health centers, Primary Health Centers (PHCs), Community Health Centers (CHCs), first referral units, or general wards of district hospitals were eligible under the programme. However, cash assistance under JSY was restricted to households classified as below the poverty line (BPL), scheduled castes (SC), or scheduled tribes (ST), if the delivery took place in an accredited private institution. For high-performing states, eligibility was restricted to two live births, and only women aged 19 and above belonging to BPL, SC, or ST households could claim the benefits. The scale of cash assistance also varied from state to state. In low-performing states, the cash assistance given to pregnant women were ₹1400 ($23.30) and ₹1000 ($16.60) for rural and urban areas respectively. In high-performing states, the cash assistance was ₹700 ($11.60) and ₹600 ($10.00), respectively, for rural and urban areas. Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers received ₹600 and ₹200 in rural and urban areas, respectively in low-performing states. In high performing states, the health workers did not receive any cash assistance. Among the mothers who were eligible for receiving the incentives in the low performing states, it was found that only in Madhya Pradesh, around 40 percent of the mothers got the money at the time of discharge from the medical centre, while in other states only a small percentage of them got the money at the time of discharge. Majority of the mothers were paid money within a week or before four weeks after the delivery.

The concept of cash transfers to recent mothers was not new in India. JSY was essentially a modification of an earlier programme called the National Maternity Benefit Scheme (NMBS), under implementation since 1995. Under this scheme, all women above the age of 19 and eligible for a BPL card were given ₹500 for the first two births. The NMBS was not specific to institutional deliveries as ₹500 was provided regardless of where the mother gave birth. The genesis of this programme was from a food security perspective as opposed to healthcare utilisation.

One key feature of the JSY programme is mobilisation of existing ASHA health workers in a local community, to identify pregnant women and counsel them for institutional delivery. These workers, trained in basic healthcare practices, worked on a freelance basis for several government health awareness programmes. The incentive amounts for ASHA workers varied from state to state and also in terms of area of residence only for the JSY programme.

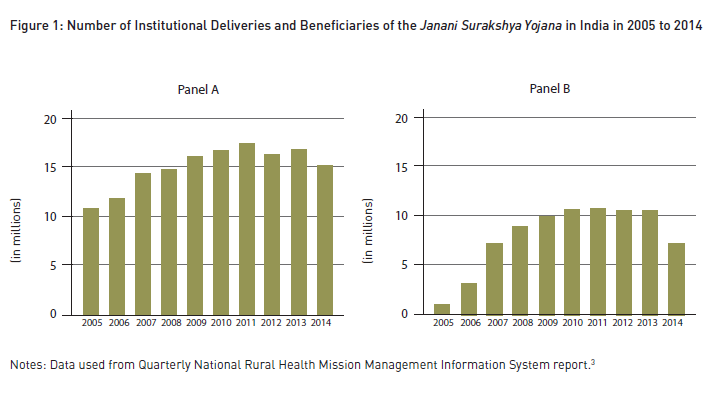

The number of beneficiaries increased over time, as reported in Panel B of Figure 1, and accompanied by a similar trend in the increase in the number of institutional deliveries (Panel A). JSY was part of a much larger National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) that was also launched in 2005 and included the provision of patient welfare committee, grants to Sub-Centres, healthcare contractors, mobile medical units, ambulatory services, mother and child health wings, etc.

Evaluation

A comparison of the beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries of the JSY programme is probably the simplest measure to find the effectiveness of the programme in inducing pregnant women to deliver their babies in hospitals. However, it is not the correct measure. Beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries of the programme vary along several dimensions. As long as these dimensions are visible such as caste and possession of below poverty line cards we can evaluate them. Factors that are not available to the researchers but determine eligibility for the programme and utilisation of healthcare simultaneously creates errors in the evaluation of the programme. This is often the problem with evaluation of many other government programmes.

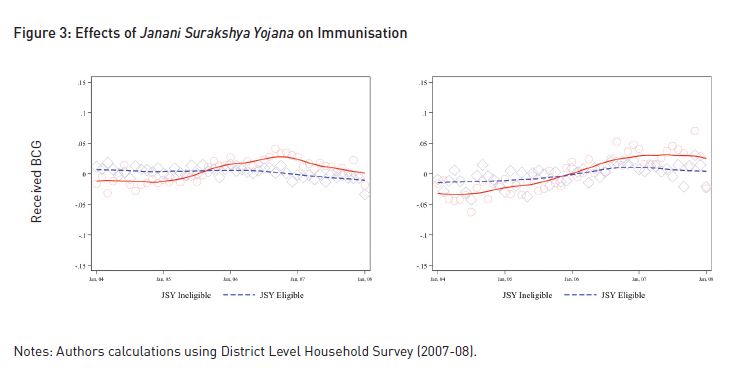

The programme also significantly increased the probability of eligible women receiving a pregnancy confirmation test, iron-folic acid supplements, prenatal care visits, tetanus injections, and a variety of immunisations for their babies. The study also found that an additional ₹100 incentive to ASHA workers increased the probability of an institutional delivery by 1.2 percent in 2007-08, with much smaller effects resulting from giving an extra ₹100 to mothers.

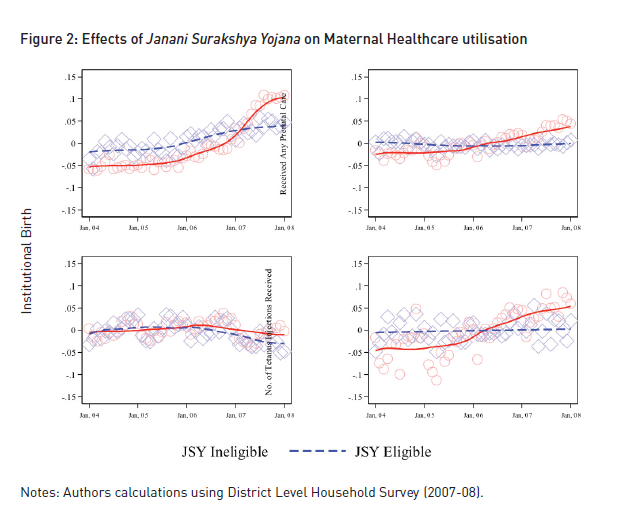

In order to eliminate such issues first we compare the healthcare utilisation practices for women who were eligible for the programme before and after the JSY programme. Effectively this measures the effect of the programme and other factors that changed at the onset of JSY for eligible women. Second, we do the same for JSY ineligible women, measuring the effects of other factors that changed concurrently with JSY but were not confined to eligible women. Finally we compare the pre-post differences of eligible women with that of ineligible women to find the effects of the JSY programme.

Findings

Using data from the District Level Health Survey III (DLHS-III) we find that the programme raised the likelihood of all eligible women delivering in a health facility by 4 percent. The effects of the programme took some time to emerge, with small effects apparent in the first two years (2005–06) and an increase of 7.2 percent in institutional delivery in the next two years.4 These effects were greater in rural areas, where the cash incentives amounts were larger for both mothers and health workers compared with that of urban areas.

The programme also significantly increased the probability of eligible women receiving a pregnancy confirmation test, iron-folic acid supplements, prenatal care visits, tetanus injections, and a variety of immunisations for their babies. The study also found that an additional ₹100 incentive to ASHA workers increased the probability of an institutional delivery by 1.2 percent points in 2007-08, with much smaller effects resulting from giving an extra ₹100 to mothers. The incentive effects for workers continue to be larger for the measures of prenatal care utilisation and immunisation. The programme reduced early neonatal mortality rate to four per 1,000 live births, whereas the programme had no effect on late neonatal mortality. These results are consistent with the increase in institutional deliveries as health institutions are more efficient in addressing complications during or immediately after childbirth than births at home.

The effects of the programme varied as per household income and also in terms of awareness about government health programmes. The results suggest that the programme was most effective for relatively richer households. However, there was an increase of 2.7 percent in institutional delivery for poorer households only when the healthcare workers were also incentivised along with the mothers. Meanwhile, for women with relatively less information on government health programmes, the programme increased the probability of institutional delivery by 4.3 percent only when the healthcare workers were also incentivised along with the mothers. These results suggest that the complementarities between the incentive given to mothers and healthcare workers are strong, especially for poorer or less-informed households.

JSY was part of a much larger National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) that was also launched in 2005 and included the provision of patient welfare committee, grants to Sub-Centres, healthcare contractors, mobile medical units, ambulatory services, mother and child health wings, etc.

Policy Implications

Our study finds that Janani Surakshya Yojana, was effective in encouraging pregnant women to deliver their babies at healthcare facilities. It also improved other maternal healthcare utilisation and immunisation of babies. We also found that the programme reduced early neo-natal mortality by 4 deaths per thousand live births. But these results are not relative to any unconditional cash transfer. The programme indeed had strong effects on maternal healthcare utilisation.

Our analysis shows that marginal effects of cash incentives are larger when they are provided to healthcare workers. The effects of the programme are significantly higher for women who are relatively more knowledgeable about other government programmes. This result supports the view that information plays an important role in the utilisation of health services.

One might safely conclude that CCT programme in the context of maternal health was successful in India. Perhaps a more intricate question is how to design a CCT programme. A CCT programme may provide incentives directly to the beneficiaries, conditional on utilisation, boosting demand for certain public services. It can make the compensation of public service providers conditional on utilisation of their service changing the quality of the services; or a combination of both. Our analysis shows that marginal effects of cash incentives are larger when they are provided to healthcare workers. The effects of the programme are significantly higher for women who are relatively more knowledgeable about other government programmes. This result supports the view that information plays an important role in the utilisation of health services. As we saw earlier, the findings also support the fact that there are strong complementarities between incentives given to mothers and health workers. Therefore, policies aimed at increasing utilisation of health services by underprivileged women should focus on incentivising both health workers and users, and increasing general awareness amongst the people about various government programmes to make them more effective. Women in the poorest quintile however, do not benefit from all aspects of the programme. These results suggest that the targeting aspect of the JSY may have been effective for some vulnerable women; it still fails to cover the poorest women.

Success of CCT programmes depends on adherence to the objective of the programme. Often households do not receive their due benefits despite satisfying the conditions while some families receive them without being eligible. Issues related to less payment, inordinate delays in payments, early discharge, etc. add to these problems. Regular monitoring of the programme and grievance cells are required to redress these issues to establish the credibility of CCT programmes such as JSY and other programmes to follow.

Income transfers raised health outcomes if the primary cause of low health is liquidity constraint. However, if poor households are pressed with competing priorities and fail to understand benefits of good health, unconditional transfers may not yield better health outcomes.

REFERENCES

1 District Level Household Survey – III.

2 The low-performing states are Uttar Pradesh, Uttaranchal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Assam, Rajasthan, Orissa, and Jammu and Kashmir.Vijayakumar, N and G Mehendiratta (2011) “Role of ICT in Sustainable Transportation,” University of Boras.

3 Source: http://nrhm.gov.in/nrhm-in-state/state-wise-information. html?id=405

4 We do not have the estimates for most recent years as the DLHS was conducted in 2007–08.