Holding governments accountable for delivering on promises and incentivising government employees appropriately is a fundamental requirement of good governance. This requirement can be met through a performance-related pay system, argues Professor Prajapati Trivedi. Can the Seventh Central Pay Commission’s recommendation to implement a performance-related incentive scheme for Indian central government employees achieve the desired results?

In its report to the Government of India on November 19, 2015, the Seventh Central Pay Commission recommended the “introduction of performance-related pay for all categories of central government employees.”

In making this recommendation, it merely reiterated and reinforced recommendations made by previous Pay Commissions in 1987, 1997 and 2008. In each case, the government of the day approved the performance-related incentive scheme (PRIS) but failed to implement it.

Pay Commissions, usually headed by a retired judge of the Supreme Court, are set up roughly every 10 years to review the salary levels and structure of central government employees.

Here, we take a close look at the recommendation of the Seventh Pay Commission and the proposed performance measurement methodology in order to better understand its design and its implications for governance in India.

Evidence to Support Performance-related Incentive Systems

To be sure, performance-based incentives are not a silver bullet. As with any public policy, there is the risk of poor design and implementation. To mitigate this risk, the Seventh Pay Commission conducted extensive research at a global level and concluded that despite the potential difficulties of a performance-related pay system, the benefits can be significant. They found that incentives for good work and achievement can, over time, transform the bureaucratic culture of the civil service into one that is focussed on meeting citizens’ and the government’s expectations of speedy and efficient delivery of services. This evidence is corroborated by the experience of many countries and summarised succinctly in the reports of the Sixth and Seventh Pay Commissions.

Similar to the current debate on the pros and cons of performance-related incentives, there was initial resistance in the late 1980s to the introduction of a policy of financial incentives for good performance for employees of central public sector enterprises (CPSEs). The policy, called Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), is a performance contract between a secretary to the government (the principal) and the chief executive of the enterprise (agent). It clearly specifies enterprise priorities, measurable goals to achieve those priorities and key performance indicators (KPIs) to track progress. The composite scores of the enterprises at the end of the year allows the government to rank them on the basis of their annual performance. The top 10 performers receive the Prime Minister’s Award for Excellence.

Despite the potential difficulties of a performancerelated pay system, incentives for good work and achievement can, over time, transform the bureaucratic culture of the civil service into one that is focussed on meeting citizens’ and the government’s expectations of speedy and efficient delivery of services.

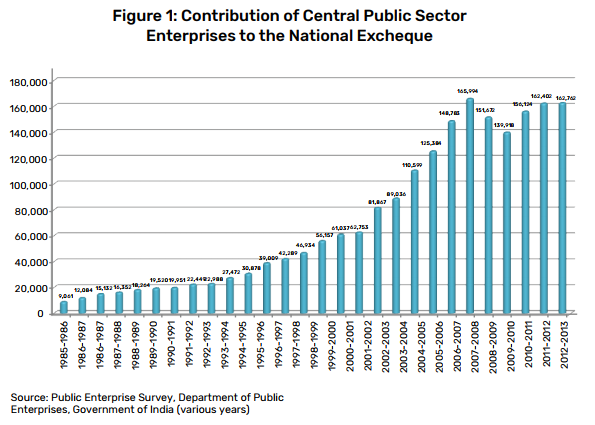

The MOU system paved the way for the eventual introduction of a performance-linked incentive scheme for CPSEs, which is today credited with a dramatic turnaround in their performance, barring some exceptions (Figure 1).

Why Performance-linked Pay Matters

However one looks at it, the opportunity cost of not implementing the performance-linked pay recommendations of four successive commissions over the past 30 years has been astronomical. Our estimate shows that by implementing this policy, the government would have saved just under ₹2,000 billion over the 25-year period from 1987-2012.1 If we extend this estimate to 2017, when the budget increased significantly, and include revenue expenditure, this opportunity cost figure may be close to ₹3,000 billion. This sum amounts to about 10% of the nation’s total external debt, 400% of its total outlay on education and 800% of its total health spending in 2017.

Given that India’s 29 states and seven union territories follow the lead of the central government, the cost to the entire nation of not implementing performance-related pay is hard to fully grasp in its enormity.

Further, the opportunity cost of the foregone benefits in terms of increased government effectiveness in non-financial areas cannot be measured. Given the government’s pervasive role in the lives of citizens, the quality of government (and hence governance) determines the competitive and comparative advantage of nations. Management experts agree that a performance incentive system is key to improving the performance of any organisation, including government departments. Therefore, it is not surprising that in its manifesto, the ruling BJP government promised that “good performance will be rewarded; non-performers will be given opportunities and training support to improve.”

To compound the already significant damage done by its failure to implement the recommendation it had approved, the central government appears to have decided to increase minimum pay from the recommended ₹18,000 to ₹21,000.

Our estimate shows that by implementing this policy, the government would have saved just under ₹2,000 billion over the 25 year period from 1987- 2012. If we extend this estimate to 2017, when the budget increased significantly, and include revenue expenditure, this opportunity cost figure may be close to ₹3,000 billion.

Proposed Design for Performance-related Incentive Scheme

Any performance-related incentive scheme has two parts. One part measures the performance of the entity (organisation, team or individual), and the second part links its performance to financial incentives. The discussion that follows in this section is accordingly divided into two parts.

Proposed Performance Measurement Methodology

The Seventh Pay Commission was of the view that the results framework document (RFD) methodology2 could be used as the primary assessment tool to link the targets of the organisation with those of individuals. Further, it recommended suitable changes in the existing annual performance appraisal report to provide the necessary linkage between the targets of the appraisal system and those of the RFD.

The following seven steps describe the essence of this performance measurement methodology.

STEP 1: Specify the long-term vision for the agency

A vision specifies the final destination of the agency. It shows where we want the agency to be in a few years’ time. It is the big picture of what the leadership wants the government agency to look like in the future.

STEP 2: Specify the objectives that will help achieve the vision

Objectives specify how to get to the final destination captured in the vision statement. They should be linked to and derived from the departmental vision.

STEP 3: Prioritise key objectives and corresponding KPIs

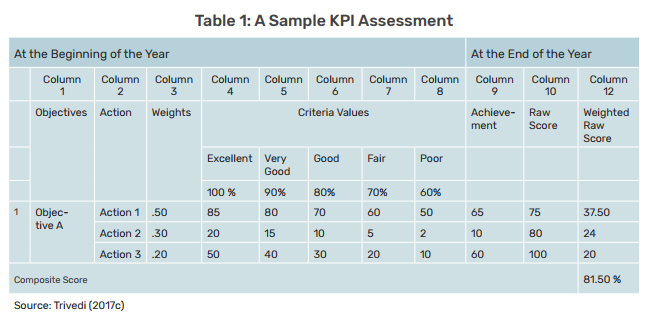

While many agencies take the first two steps, they flounder when it come to the next steps. As argued previously by this author, objectives and corresponding KPIs should be prioritised and specific weights attached to these objectives (Trivedi, 2017b). As depicted in Table 1 (column 3), these weights must add up to100%.

STEP 4: Agree on how to measure deviations from the target

Instead of a single point target, we need to agree on the entire performance range (Table 1, columns 4-8). This scale of criteria values allows us to accurately measure performance at the end of the year. Without such clear understanding, performance measurement remains subjective.

A document incorporating the first four steps is referred to as a performance agreement (or RFD). New Zealand pioneered this innovation as part of the New Public Management (NPM) revolution that swept across the world in the 1980s, and in the United States, the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 made performance agreements mandatory for US government agencies.

Once an agreement has been reached on steps 1-4, government agencies should be allowed sufficient operational freedom to achieve the agreed-upon targets, that is, “accountability” must be coupled with appropriate “autonomy.” This is the essence of management by objectives. At the end of the year, government agencies submit their achievements against the targets to the designated authority and we calculate their bottom line achievement as follows (Steps 5-7).

STEP 5: Calculate the raw achievement score for each KPI

By comparing actual achievement at the end of the year with the range of criteria values agreed at the beginning of the year, we can calculate the precise raw score for each KPI (Table 1, columns 9-10).

STEP 6: Calculate the weighted raw score for each KPI

Multiply the raw score for each KPI with the corresponding weight for that raw score (Table 1, column 11).

STEP 7: Calculate the composite performance score – the bottom line

Add up all the weighted raw scores to get the composite score the bottom line. For example, in Table 1, this number is 81.50%. It measures the degree to which a government department was able to achieve the agreed-upon objectives.

The Seventh Pay Commission endorsed this methodology for measuring the performance of government departments. Indeed, this methodology is transcendental in its application. Different departments will have different sets of objectives and corresponding success indicators. Yet, at the end of the year, every department will be able to compute its composite score for that year. This composite score will reflect the degree to which the department was able to achieve the promised results.

Proposed Linkage between Performance and Total Incentive

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), designated as the nodal agency for the implementation of the Sixth Pay Commission’s recommendations, had proposed a variable pay component for central government employees based on the composite score of the departmental RFD. These incentives were to be available both at the individual and team/ group levels and were to be paid out of “efforted” cost savings, that is, cost savings resulting from managerial efforts and not due to exogenous (windfall) factors. Cost, for this purpose, is defined as the sum of all inflation-adjusted operational/ overhead costs.

Both the Sixth and the Seventh Pay Commissions agreed with the broad outline of the DoPT’s incentive scheme, but differed with respect to financing it. The Sixth Pay Commission was in agreement with the DoPT that performance awards should be revenue neutral and funded out of savings generated by individual departments. The performance award amount was linked to the savings achieved by the department. However, the Seventh Pay Commission did not think it was essential to fund performance awards out of “efforted” savings. Indeed, by removing a major excuse for not implementing the performance-related incentive scheme, the Seventh Pay Commission may have moved the ball further towards the goal of implementation.

The Way Forward

The current government has an ambitious agenda. It has launched many aspirational and inspirational schemes and projects. Yet, it is widely believed that this robust vision has not been matched by an effective delivery and accountability system. The performance-related incentive scheme proposed by the Seventh Pay Commission seems to be exactly what the doctor ordered to reduce the potential gap between rhetoric and reality.

ENDNOTES

- This sum was calculated using time series data available on request, and using the following assumptions:

a. a rate of return of 7%

b. The salary component in non-plan expenditure is around 70% of total establishment

c. In 2011-12 Budget Estimates, it was assessed that the non-Plan component of salary comprises 37.15 % of expenditure under selected heads (including salary) considered for savings. The same was considered for all the years while estimating salary component. The opportunity cost estimate figure does not include the costs of implementing the PRIS (as it is expected to be insignificant). - For education outlay of ₹79,685.95 crore, see Nanda (2017). For health outlay of ₹48,880 crores, see The Hindu (2017). External debt figures are taken from a September 15, 2017 press release by the Ministry of Finance.

For Further Reading

The Hindu (2017). Health Budget: A moderate rise with no bold initiative. TheHindu.com, February 1.

Kamensky, J (2013). What Does Performance Management Look Like in India? (Washington, DC: IBM Centre for the Business of Government).

Nanda, Prashant (2017). Union budget 2017: Education outlay increases 9.9% to ₹79,685.95 crore. LiveMint.com, February 1.

Trivedi, P (1990a). Memorandum of Understanding: An Approach to Improving Public Enterprise Performance (New Delhi: International Management Publishers).

— (1990b) “Lack of Understanding on Memorandum of Understanding”, Economic and Political Weekly, 25 (47): 175-182.

— (2010) “Performance Monitoring and Evaluation System for Government Departments”, The Journal of Governance, 1(1): 4-19.

— (2013) “Performance Monitoring and Evaluation System (PMES)”, in Proceedings of the Global Roundtable on Government Performance Management System (New Delhi: UNDP).

— (2017a) “The Rise and Fall of India’s Government Performance Management System”, Governance, 30 (3):

— (2017b). “How to Avoid Four Fatal Flaws when Designing your Government Performance Management System”, PA Times, American Society for Public Administration, July 14.

— (2017c). “Seven Steps for Creating a Bottom Line in the Government,” PA Times, American Society for Public Administration, August 11