The Bharti Institute of Public Policy organised a symposium on “International Experience with Monitoring and Evaluation in Government” where former bureaucrats and experts shared best practices. A report on the recommendations and proceedings.

For governments to effectively serve citizens and to cultivate public confidence they must focus on performance management and become resultsoriented along with process orientation. It is in this context that effective monitoring and evaluation (M&E), of government programmes and schemes becomes important.

The findings and recommendations of the Global Roundtable on Government Performance Management, discussed recently at a symposium organised by the Bharti Institute of Public Policy on ‘International Experience with Monitoring and Evaluation in Government’, provide important insights in this respect.

Presentation of M&E learnings and best practices from various geographies including Brazil, UK, Malaysia, USA, Kenya and Indonesia through country case studies, offered a wide range of options and solutions for evaluating and monitoring policy initiatives and government programmes. Drawn from the years of experiences of former bureaucrats and experts, the case studies were intended to identify ways to fi ne tune the Indian M&E systems.

For governments to effectively serve citizens and to cultivate public confidence they must focus on performance management and become results-oriented along with process orientation.

Making a clear distinction between monitoring, which is about tracking progress towards achieving the goals, and evaluation which is more about achieving the goals themselves, the experts were unanimous in their view that M&E requires different perspectives and skills and fi ner understanding of what it stands for.

Setting the tone Dr Prajapati Trivedi, Senior Fellow, Bharti Institute of Public Policy, ISB, highlighted the relevance and need for an in-depth understanding and discussion on various aspects of M&E and more particularly India’s experience with designing and implementing Performance Management and Evaluation System (PMES), for government departments. For a truly effective performance management, the government must focus on a Performance Information System, Performance Evaluation System and a Performance Incentive System, he said, going on to add that though all the three components existed in India till 2009, they were not organically connected and therefore were not yielding results.

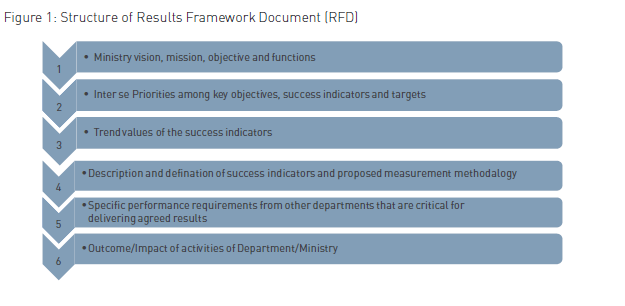

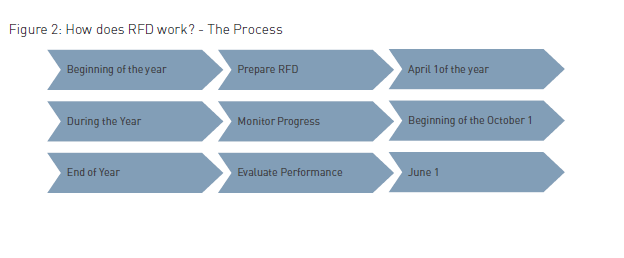

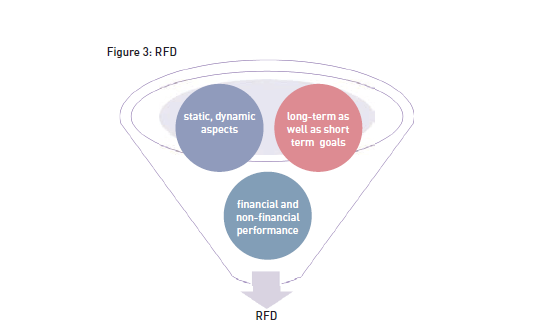

The Cabinet Secretariat, Government of India is responsible for Performance Monitoring and Evaluation System (PMES). According to this system, at the beginning of each fi nancial year, with the approval of the Minister concerned, each Department is required to prepare a Results Framework Document (RFD), which must include priorities and agenda, of the ministry concerned.

Thus the RFD enables a Ministry/Department to outline its strategy and plan the path for achieving its vision.

After six months, the achievements of each Ministry/Department are reviewed by a committee chaired by the Cabinet Secretary and the goals are reset depending upon the priorities of the government at that point of time. This enables the government to factor in the unforeseen circumstances such as draughts, epidemics, floods, etc. At the end of the financial year, each Ministry/Department prepares a report of its achievements against the annual targets set in the RFD.

For a truly effective performance management, the government must focus on a Performance Information System, Performance Evaluation System and a Performance Incentive System. They existed in India till 2009 but were not organically connected and therefore were not yielding results.

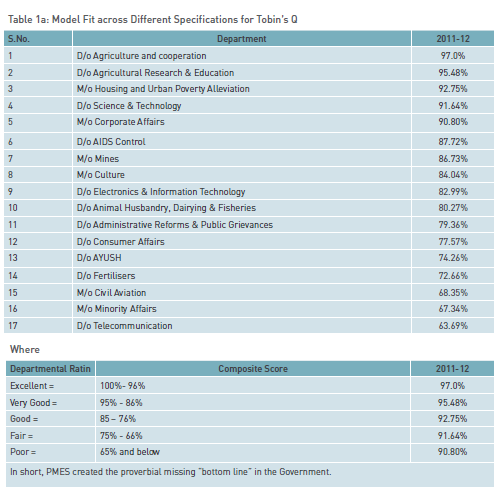

(RFDs are aligned to five year plan and are updated as the circumstances keep changing.) Thus RFD is a comprehensive mechanism for reviewing Departmental performance. They are available on departmental websites at the beginning of the year and at the end of the year, the PMD compares the achievements of each ministry/department against the agreed targets at the beginning of the year and is able to calculate a performance score. A score of 100 percent would signify that the ministry/department achieved all its targets. These scores are included in the Annual Reports of the departments/ministries and placed in the Parliament. A sample of Composite Scores collected from the Annual Reports of the ministries are given below:

Chopra, Former Secretary with the Government of India, explained the concept of Results Agreements (RA)s , that the country follows. Heads of Government Departments, at the State level, are required to have these agreements for a period of four years, unlike Indian RFDs which are for a period of one year.

Similar to RFDs, achievements are scored against the commitments made in RAs, which function at two levels:

- At the level between State Government and the heads of the State Secretariats and agencies monitoring results / outcomes for the society.

- Between the heads of agencies and their respective teams. At this level contribution of a staff member is clearly identified.

Performance Agreements are also signed with NGOs – when funds are released for implementation of any programme. Based on these experiences perhaps the following lessons could be derived for India:

- Extension of RFDs to major municipal corporations, urban development bodies and public utilities could be explored.

- Similar Performance Agreements can be signed with NGOs – a documentation of mutual obligation for executing any welfare programmes

- A two-step RAs can be implemented in India, both at the federal and state level.

While most M&E approaches from across the world are used in India to varying degrees currently, a culture of accountability for output or outcomes should be inculcated taking other countries’ successful experiences into account.

K Padmanabhaiah, Former Secretary, Home Affairs, shared details of the system in UK which also follows a mechanism of framework agreements on each agency’s general mission and the responsibilities of the Minister and Chief Executive. A complementary annual performance agreement between the Minister and the Chief Executives sets out performance targets for that department. The ministers are responsible for setting targets and the departments’ performance on the basis of quarterly report sent to their respective ministry. Over the years a single set of national indicators have evolved to be used by both the central government and by the local government.The overriding emphasis in the UK system is also on service delivery and customer satisfaction for performance management.

A key takeaway for India from the UK system is that delivery is the key in the entire performance chain.

US on the other hand, M&E is governed under the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA), where the President signs performance agreements (similar to Indian RFDs) with Secretaries. Further the Secretaries sign performance agreements with their Assistant Secretaries. Accountability for deliverables and performance management thus goes down to the lowest levels. GPRA makes it mandatory for all government agencies to design mechanisms for improved performance by setting goals, measuring results and reporting progress.

These agreements include departmental vision, mission, objectives and annual targets. Achievements are measured against these by the Congress.

Clearly, India could do with a similar law which gives teeth to the Performance Management Division (PMD). It would help in stating the ‘rules of the game’ clearly and the processes, procedures, deliverables and results are streamlined and, most of all, made legally mandatory.

Indonesia has a similar mechanism like Indian RFD; albeit with a different nomenclature as Performance Contracts – signed between the concerned minister and the president of the country. However, as part of the Performance Contract other Ministries, which though not directly responsible for the results of the programme but have complimentary role in implementing them, are also identifi ed and targets affixed. Their Performance Contracts thus enable coordination amongst different ministries.

Besides, Indonesia has an online reporting system called Lapor (meaning ‘report’ in Indonesian) which basically enables common people to provide, feedback on public services. This initiative promotes transparency, public participation and coordination across government departments. It further facilitates getting feedback from remote locations about the status of ongoing projects.

Indonesia has an online reporting system called Lapor (meaning ‘report’ in Indonesian) which enables people to provide feedback on public services promoting transparency, public participation and coordination across government departments.

Similarly, Kenya has a Performance Contract System (PCS) that covers the entire public sector – about 40 ministries, 130 public enterprises, 175 local authorities covering about 0.7 million staff to be monitored. It also takes into account customer satisfaction, work environment and employee satisfaction.

The PCS oversees the Performance Contracting Division (PCD) which is a part of the Department of Planning and Devolution under the Prime Minister. This reflects the political will and commitment to PCS.

Another distinct feature of PCS is its objectivity, neutrality and independence. The Performance Contracts are whetted and evaluated by a nongovernmental body comprising of ex-civil servants, academicians and industry and private sector experts. Results of Performance Evaluation (including ranking) are announced for public knowledge by the political executive. And the three top performing institutions receive financial incentives – topper gets a full month’s pay, winners of second and third position get 75 percent and 50 percent of the pay respectively.

India can learn a lot from the Kenya’s Performance Contract System. Following are some important practices.

- The Kenyan system covers all ministries, but in India RFD exempts four/five Ministries or Departments. The RFD system should embrace all ministries and may also take under its ambit urban local bodies – municipalities and urban development bodies.

- Evalution reports should be made public.

- Feedback from Kenya’s citizens/customers is given very high weightage in evolution performance, in India impact assessment is often regarded as the indicator of success. Customer satisfaction survey should be incorporated.

- Financial incentives to motivate the staff/ institution is something we may also consider – but it may stress our already over-burdened exchequer. So further this could be debated.

The symposium thus set the context for building a government-wide M&E system in India and outlined some tools, methods, and approaches to M&E: performance indicators, feedback-based evaluation, formal surveys, participatory methods and impact evaluation. While most of these approaches are used in India to varying degrees currently, a culture of accountability for outputs/outcomes should be inculcated taking other countries’ successful experiences into account, the panelists agreed.

M&E requires different perspectives and skills and finer understanding of what it stands for. Monitoring, is about tracking progress towards achieving the goals, and evaluation is more about achieving the goals themselves.

Reported by Suchetana Bauri, Manager, Marketing and Communications, Indian School of Business.