In this article, Professors Sunil Wattal, Gordon Burtch and Anindya Ghose explore various dimensions of the growing phenomenon of crowdfunding as a powerful instrument of entrepreneurial finance. They look at the upsides and potential pitfalls of this rapidly emerging industry and efforts underway to better understand and regulate it. They also consider the potential of crowdfunding as a “democratising” process to foster economic growth, innovation and social change in both the developed and developing world by removing the traditional barriers to entrepreneurship.

“Need start-up capital − and fast? You may want to try crowdfunding, a money-raising strategy that’s become increasingly popular in recent years” – The Wall Street Journal, November 27, 2011

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is the engine of growth for an economy. As enterprising individuals from places such as Silicon Valley or Boston or New York seek access to capital, they often turn to established sources such as venture capital firms, angel investors, high interest debt products, and friends and family. However, access to venture capital firms and angel investors often depends on who one knows and one’s location, rather than the potential or quality of one’s innovation. Banks may require a co-signer or collateral before offering loans to entrepreneurs; moreover, such loans are deemed risky by banks and carry high rates of interest. Also, not everyone will have the financial backing of friends and family to fund their ventures. In other words, traditional sources of finance have embedded mechanisms that often stifle creativity and innovation.

With the growth of the Internet and web 2.0, we have witnessed the participation of masses of individuals (crowds) in several processes that were previously exclusive in nature, reserved for a select few. For example, product reviews are no longer the privilege of expert reviewers and consumer reports; anyone with a computer and Internet connection can now offer their opinion. Threadless allows anyone to try their hand at designing T-shirts, and Netflix extended an open invitation to the public to propose improvements to their content recommendation system. Applying the same concept to entrepreneurial finance, crowdfunding has given rise to a new business phenomenon, enabling entrepreneurs to source capital from any individual with both the means and the interest. Figure 1 presents a graphic that summarises the power of crowdfunding.

The three friends turned to Kickstarter.com, a recently established crowdfunding platform, and posted details of their proposed invention, which they named Revolights. In addition to soliciting donations, they also offered to “reward” donors who contributed US$200 or more with a unit of the product, once manufactured (in effect, using crowdfunding to pre-sell their product). The crowd responded massively. In a few weeks, Kent, Jim and Adam had raised US$215,000 from over 1,440 people through the crowdfunding process.

Consider the case of three friends, Kent, Jim and Adam in the Midwestern United States who, in 2011, wished to design a unique set of light-emitting diode (LED) based headlights for bicycles that could be mounted on the rims of a wheel. The entrepreneurs anticipated a funding requirement of US$43,000, which they decided to raise through crowdfunding. They believed that their idea would appeal to biking enthusiasts and calculated that if even a small fraction of this group supported them with small sums of money (as low as US$1), they would be able to raise the required amount. So the three friends turned to Kickstarter.com, a recently established crowdfunding platform, and posted details of their proposed invention, which they named Revolights. In addition to soliciting donations, they also offered to “reward” donors who contributed US$200 or more with a unit of the product, once manufactured (in effect, using crowdfunding to pre-sell their product). The crowd responded massively. In a few weeks, Kent, Jim and Adam had raised US$215,000 from over 1,440 people through the crowdfunding process. This example highlights how crowds can be harnessed to support financing for those entrepreneurial ventures that may not appeal to select individuals (venture capitalists [VCs] or angel investors), but which appeal instead to a broader group of individuals (in this case biking enthusiasts). Ordanini et al. (2010) define crowdfunding in more formal terms as “a collective effort by consumers who network and pool their money together, usually via the Internet, in order to invest in and support efforts initiated by other people or organizations.”

The question that arises, then, is why individuals would contribute money to support total strangers. Prior research (Burtch et al., 2013a) suggests that the main motivations for individuals to contribute include altruism, reputation and monetary rewards. Four main types of crowdfunding formats exist today − donation-based, reward-based, loan-based and equity-based − which are primarily differentiated by the types of projects supported and the incentives that contributors may receive. In donation-based crowdfunding, projects (campaigns) mainly come in the form of charitable activities, and contributors are usually not offered any explicit compensation for the money they provide. In reward-based crowdfunding, contributors are offered specific rewards for their financial support. Rewards can take the form of thankyou notes, t-shirts, or, as in the case described above, a unit of the product (e.g. electronics, games, music albums or movie digital video discs [DVDs]) being funded. In loan-based crowdfunding (e.g. Prosper. com), contributors expect eventual repayment (sometimes with interest) on the money they lend. Finally, equity-based crowdfunding (e.g. Symbid. com), as the name suggests, is a type of crowdfunding where contributors can purchase a stake in the company seeking funding. These investors hope to get rewarded as the company grows and increases in value

The Crowdfunding Process

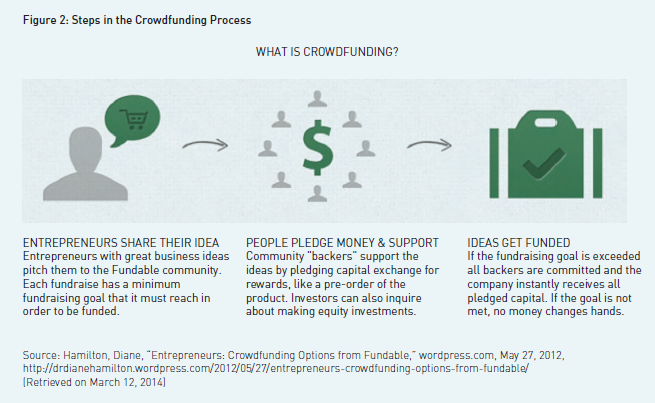

A typical crowdfunding process is shown in Figure 2. It starts when the project sponsor posts the description of the project for which funding is sought. This is referred to as the “pitch”. The pitch contains textual and visual descriptions. It also contains information about the sponsors of the project, the planned duration of fundraising, the amount of money required (referred to as the “threshold”) and any incentives offered to the contributors. Once the pitch is live on the crowdfunding website, contributors offer money until the pitch reaches its expiration date. Once the amount of money raised surpasses the threshold, it is paid to the project sponsors minus the platform’s administrative fee (typically 4-5%). While the sponsors typically receive nothing if the contributions do not reach the threshold, some crowdfunding platforms do allow the sponsors to keep any amount raised (e.g. flexible fundraising campaigns at IndieGoGo.com). Once the money is raised, the project sponsors are expected to spend the funds in accordance with the activities outlined in the project pitch and deliver rewards or repayment to the contributors in a timely fashion (in the case of reward- and loan-based crowdfunding). Usually, the sponsors post regular updates to the crowdfunding platform, detailing the progress of the project to keep investors informed.

Pros and Cons of Crowdfunding

The main benefit of crowdfunding is that it exposes an idea to a wide variety of potential contributors across the world. Therefore,’ success need not be restricted by the people they know (friends and family or venture capitalists), but only by their own innovativeness. Thus, crowdfunding takes a big step towards “democratising” entrepreneurial finance by letting people vote with their money on which ideas deserve funding and which ones do not. This in effect, lowers the barriers to entry for new startups. Additionally, crowdfunding exposes an idea before a wide audience who give feedback in the formative stages of a product. Such feedback can be invaluable for guiding the development of a new product. Most types of crowdfunding enable project sponsors to retain equity and control over their projects, in contrast to venture capital financing where the owners sell stake in the company. Crowdfunding can also generate viral marketing where users can share project details with others, sometimes generating strong word of mouth. A consequence of this word of mouth is that some crowdfunded projects raise more money than expected; for example, in the Revolights example mentioned earlier, the founders raised more than US$200,000 in spite of asking for less than US$45,000. At the same time, crowdfunding has its own peculiar challenges. The main concern is that project sponsors need to tailor their pitch specifically for social media in order to create a successfully funded campaign. They have to pay attention to the pitch wording, quality of the video and try to get some high profile endorsements. The other drawback of crowdfunding is that ideas have to be put in the public domain early, and there is a possibility that someone else may copy the idea. Also, the diverse stakeholders may have conflicting expectations about the project and it may be difficult for the sponsors to manage all these expectations. The viral nature of crowdfunded projects has another potential downside in that the negative feedback from not meeting contributors’ expectations may get amplified, which can damage he sponsors’ reputation and prevent them from raising funds in the future

Crowdfunding takes a big step towards “democratising” entrepreneurial finance by letting people vote with their money on which ideas deserve funding and which ones do not. This in effect, lowers the barriers to entry for new startups. Additionally, crowdfunding exposes an idea before a wide audience who give feedback in the formative stages of a product. Such feedback can be invaluable for guiding the development of a new product.

Current State of Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding is growing in importance as a fundraising mechanism in microfinance, charitable giving and entrepreneurial finance. The financial crisis of 2008 and the associated shortage of funding for new ventures provided an impetus to crowdfunding. A recent report by Massolution (2012) suggests that, as of 2012, more than one million projects have been funded on crowdfunding websites worldwide, with more than US$1.5 billion raised. The total number of such markets worldwide is estimated at 536 in December 2012. This report also suggests that the funds raised have been growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 63%, and the number of crowdfunding marketplaces have been growing at a CAGR of 49%. Crowdfunding has received prominence in the United States with the JumpStart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act signed by President Barack Obama in 2012, which legalises the sale of certain types of equity through crowdfunding markets. A recent report by the World Bank (2013) suggests that the developing world has the potential to leapfrog the developed world in terms of leveraging crowdfunding to stimulate innovation and create new jobs. Some of the projects highlighted in the report include a highly efficient stove in Kenya, flywheel storage for wind/solar energy in Haiti and a solar charger for cell phones in Africa. The report estimates that crowdfunding in developing countries will grow to US$95 billion within the next 20 years.

A recent report by the World Bank (2013) suggests that the developing world has the potential to leapfrog the developed world in terms of leveraging crowdfunding to stimulate innovation and create new jobs. Some of the projects highlighted in the report include a highly efficient stove in Kenya, flywheel storage for wind/ solar energy in Haiti and a solar charger for cell phones in Africa. The report estimates that crowdfunding in developing countries will grow to US$95 billion within the next 20 years.

State of Equity-Based Crowdfunding

Of the different types of crowdfunding, equity based crowdfunding has received special attention due to certain unique characteristics. Equity-based crowdfunding enables contributors to acquire a stake in the company they are funding, thus providing them with the potential to earn windfall returns if the new venture is successful. On the other hand, the contributors can lose their entire investment if the venture fails. The fact that most crowdfunded ventures may be at the idea stage without a product or prototype further exacerbates the risk. Equity-based crowdfunding is legal in certain European countries such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has proposed a set of guidelines that will provide a framework to operationalise equity based crowdfunding. The guidelines are expected to go into effect in early 2014.

The main risk in equity-based crowdfunding can be classified into three types – investor protection, due diligence and investor rights. Investor protection refers to issues such as what disclosures should be provided to investors, restrictions on marketing of crowdfunded securities, ensuring that investors buy no more shares than allowed by law and protecting the privacy of investor information. Due diligence refers to such issues as what audit standards project sponsors should adhere to, the inability of the crowd to value crowdfunded investments, provision of eBay style reputation mechanisms, and laws governing third-party certification agencies such as Crowdcheck. Finally, the issues pertaining to investor rights are whether the stake in crowdfunded projects can be traded and whether investors should have voting rights.

Crowdfunding in India

Crowdfunding is taking hold in India with donation based crowdfunding and microfinance constituting the bulk of the crowdfunded marketplace. Platforms such as Wishberry, IgniteIntent, Ketto, Start51, Milaap and Rang De have been launched in the last few years. Notable examples of crowdfunding include the movie “I Am,” which, according to a March 2012 article in The Times of India, raised close to Rs 10 million over a nine-month period. Crowdfunding holds promise in India due to the new rule in the Companies Act 2013 requiring certain companies to spend 2% of their three-year average profit on corporate social responsibility, a requirement that may promote funding for crowdfunding projects. However, equity-based crowdfunding is not yet legal in India. The key question surrounding equity-based crowdfunding in India is whether it would be akin to a public offering under section 67 of the Companies Act. This is more likely to happen if the offer to buy shares is made to more than 50 individuals, which will surely be the case with equity-based crowdfunding. A public offering attracts scrutiny and disclosure norms that many ventures (and startups in particular) in the very early stages cannot afford. Another question that arises is whether the crowdfunding platforms themselves have to register as broker-dealers with the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). Therefore, it is imperative that the Indian legal system enacts changes similar to those in the United States to enable equity-based crowdfunding. In addition to the legal barriers, the concept of giving money to finance strangers’ businesses is alien to Indian culture. Moreover, there is likely to be scepticism and concerns regarding fraud.

Crowdfunding in Practice – Insights from Academic Research

Crowdfunding is a complex phenomenon and combines features of several web technologies, such as e-commerce (because crowdfunding involves the exchange of products and money), social media (because crowdfunding involves aspects of viral marketing and electronic word of mouth), and two sided markets (as crowdfunding platforms entertain both a demand side, i.e. funders, and a supply side, i.e. entrepreneurs). As a result, crowdfunding provides a rich set of data pertaining to the amounts and timing of contributions, browsing behaviour, consumers’ social networks, affinity networks, referrals, demographics of consumers, comments, geographical locations, reviews, ratings, characteristics of entrepreneurs, and repeat contribution activity, among many others. Many academic researchers are leveraging this data to uncover insights on consumer behaviour in crowdfunded markets to inform firms on more efficient design of these markets and regulatory bodies on drafting effective policies for crowdfunding. Below, we summarise research findings on two key aspects of crowdfunding – successful fundraising and marketplace design (Burtch et al., 2013a; Burtch et al., 2013b; Liu et al., 2012; Lorenz et al., 2011; Mollick, 2013; Woolley et al., 2010; Zhang and Liu, 2012, and Agarwal et al. 2011).

Successfully funded projects are key to crowdfunding – for project sponsors, contributors and the marketplace. The following factors have been identifi ed as critical to successful fundraising for a project:

- The duration of the fundraising campaign is a double-edged sword for the overall success of a project. A long campaign may signal a lack of urgency or excitement on part of the project sponsors and lead to a lack of interest among the public, and the project may not get funded. On the other hand, a long campaign is associated with longer exposure/ word of mouth for the project, which may lead to better adoption of the product once it is in the market. Therefore, project sponsors should decide on the duration of their fundraising campaign carefully.

- Very high or unrealistic fundraising targets are associated with a high probability of failure.

- Projects that are described in detail and utilise media such as photos and videos are more likely to succeed in their fundraising goals.

- Constant updates on the project to the public and use of social media such as Facebook and Twitter are also associated with high project success.

- Projects sponsors who show social responsibility by having funded other projects in the past are more likely to successfully fundraise. Marketplace design consists of the provisions and features provided in the market that encourage optimal behaviour on part of the participants – project sponsors and contributors. Research has shown that the following features of crowdfunding markets are effective in influencing consumer behaviour: Research suggests that earlier contributors tend to crowd out later contributions – in other words, contributions to a project slow down if it receives lot of contributions initially

- Strategies such as offering to provide refunds, making matching contributions and demonstrating seed capital received from other sources helps a crowdfunding platform boost contributions.

- In global crowdfunded marketplaces, cultural distance is inversely related to the probability of a transaction between two parties. However, the effect of culture is mitigated by geography, i.e. the negative impact of cultural distance is mitigated if the lenders and borrowers are located far apart. For example, a lender in India is more likely to contribute to a project in Africa than in Bangladesh

- Contributors who contribute extreme amounts (very high or very low amounts) are more likely to hide their names and the size of their contributions from the public. Therefore, anonymity mechanisms may be necessary to invite high contributions.

- Subsequent contributors are influenced by the immediately preceding contributions, an effect known an anchoring. High anchors may spur contributors to match or surpass them; on the other hand, low anchors may drag down subsequent contributions.

Crowdfunding holds promise in India due to the new rule in the Companies Act 2013 requiring certain companies to spend 2% of their three-year average profit on corporate social responsibility, a requirement that may promote funding for crowdfunding projects. However, equity-based crowdfunding is not yet legal in India. The key question surrounding equity-based crowdfunding in India is whether it would be akin to a public offering under section 67 of the Companies Act. This is more likely to happen if the offer to buy shares is made to more than 50 individuals, which will surely be the case with equity-based crowdfunding.

Conclusions

In summary, crowdfunding has emerged as a novel way to democratise fundraising by small businesses and entrepreneurial ventures. While the developed world (such as the United States and Western Europe) is witnessing the rise of crowdfunding for entrepreneurial ventures, the developing world is seeing more crowdfunding for social projects and microfinancing small businesses. In effect, it provides an effective mechanism for moving capital from surplus to where it is deficit and creating economic and social opportunities for a wide population. For example, most projects on Kiva.com are located in developing countries in Africa and South America, but most of the project sponsors are located in Europe and the United States. Countries such as India not only need to provide incentives for high-quality projects to be launched on crowdfunding, but also effect social change by fostering trust and launching efforts to encourage people to contribute on these markets.