How many businesses survive more than 100 years? Of the businesses that do survive, how many remain financially robust? If the lifespan of a company on the Standard and Poor’s (S&P) 500 list is an indication of longevity, then evidence shows that it has shrunk from 33 years in 1964 to 24 years by 2016. By 2027, it is forecast to shrink to just 12 years.1 Put differently, at the current survival rate, more than 75% of the companies currently quoted on the S&P 500 would disappear in the next decade.

Family-owned businesses tend to mirror these survival patterns. A large proportion of family-owned businesses struggle to survive beyond the second or third generations. According to the Family Business Institute, only 30% last into a second generation. Only 12% remain viable into a third and a minuscule 3% continue into the fourth generation or beyond. What have these 3% businesses and the family business owners done differently that is likely to have contributed to their resilience? What can be learnt about the groups that have lived beyond 100?

Understanding Longevity

Over the last five years, we have been following a group of five British family-owned businesses that are more than 100 years old. These five family businesses – William Jackson Food Group, Bibby Line Group, Samworth Brothers, Thatchers Cider, and Wates Group – were all founded in the 19th century. Still tightly held within the family, all these businesses continue to be deeply embedded in the local communities where they first started. Our interest in them was to engage with the families to understand the traditions, practices and leadership that have enabled these businesses to not only be resilient but also grow over many generations.

A large proportion of family-owned businesses struggle to survive beyond the second or third generations. Only 30% last into a second generation while 12% remain viable into a third and a minuscule 3% continue into the fourth generation or beyond.

Profiles of the ‘Beyond 100’ family businesses

- The William Jackson Food Group’s (WJFG) foundations were laid by William Jackson and his wife Sarah in 1851 when they opened W. Jackson Grocer and Tea Dealer at Scale Lane in Hull. Today, WJFG is a diversified food group which generates an annual turnover of close to £300 million. Privately held by the family, and still based in Hull, the group has a portfolio of several food businesses – such as Jackson’s Bakery, Wellocks, The Food Doctor, My Fresh and Abel & Cole – all operating in different but complementary markets.

- The Bibby Line Group is a diverse £1billion global enterprise, operating in 16 countries and employing around 4,000 people in various sectors including retail, financial services, distribution, marine and construction equipment hire. Founded in 1807 by John Bibby, the Bibby Line Group is headquartered in Liverpool and is regarded as one of the United Kingdom’s (UK’s) oldest family-owned businesses.

- Samworth Brothers is a fourth-generation family business that employs around 8,000 people and has a turnover of £1billion in the region. Established in 1896 by George Samworth, Samworth Brothers has kept its focus on the food industry, building its reputation on quality and a long-term investment approach. Headquartered in Melton Mowbray, the family business group has 17 business units each with its own board of directors.

- Thatchers Cider was set up in 1878, in Sandford, North Somerset, where the company’s headquarters remain to this day. Thatchers Cider is one of the UK’s best known and largest independent cidermakers, supplying draught, bottled and canned cider. Currently run by Martin Thatcher from the fourth generation, Thatchers continues to make substantial investment both in its business and local community. It maintains a strong presence in international markets, selling in over 22 countries worldwide.

- The Wates Group was set up by Edward Wates in 1897 as a furniture business in south London. The enterprise first ventured into housing when Edward bought a plot of land and built two houses with the help of his brothers who were in the construction business. Today Wates Group consists of several businesses, all operating in the built environment sector. In 2017, it reported a turnover of £1.62 billion. The group is led by James Wates and his cousins, from the fourth generation, who work closely with industry professionals to co-create value for the business and society.

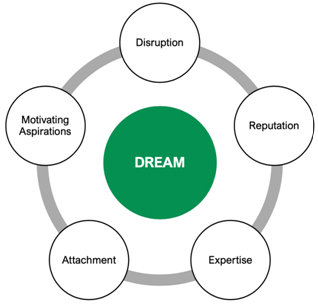

We have collated insights from our cases into a decision-making framework for family owners who wish to learn from long-lived family-owned businesses. We call this framework DREAM.

DREAM: A Guiding Framework for Building Longevity

Every generation invariably struggles with questions of the longevity of the family-owned business. Are we making the right long-term investments? Have we built enough competence in the next generation? Do we have trusted and competent executives to grow the business? Be it the second generation, the third or even a family-owned business that has been around for more than 100 years, questions such as these often keep owners on the lookout for a more comprehensive guide to understanding the determinants of long-term sustainability.

Every generation invariably struggles with questions of the longevity of the family-owned business. Are we making the right long-term investments? Have we built enough competence in the next generation? Do we have trusted and competent executives to grow the business?

First and foremost, our study shows that the bedrock of longevity is in strong business foundations. In a business environment that is characterised by volatility and uncertainty, the need for dealing with disruptions is more urgent than ever. Disruption happens when the way in which a business generates value suddenly ceases to exist. This may be due to changes in the external operating environment such as new regulations, new technologies, the emergence of a large competitor or internal reasons such as disruption caused by the breakdown of supply chains. Therefore, how a family-owned business develops the capability to identify disruptive threats, mobilise resources and plans responses, i.e., its Disruption Strategy, must be considered more systematically by the leadership team.

A central theme that stood out in our research was the focus on developing and transferring values – a strong emotion of pride in the business, the family history and connection with the larger community as part of the family. The family’s reputation, or the family name, is a widespread belief about the characteristics of what the family and business stand for. We find that the businesses that thrive have built this emotional pride in the family identity, and we identify it as the Reputation Strategy. A reputation strategy serves as a guide to moral resilience over generations. As businesses grow and new generations join the business, it acts as a guide to what the family will or will not do.

An Expertise Strategy, asks: what are the mechanisms by which the family is developing the family talent pool through the disciplined investment of resources over time?

Families that have successfully navigated challenges have also been good at developing new capabilities. Ideally, these capabilities have been developed in the family. But if that was not possible, then there are mechanisms to give the family time to develop these capabilities while meeting the gap with professional managers. We call this the building of an Expertise Strategy, which asks: what are the mechanisms by which the family is developing the family talent pool through the disciplined investment of resources over time? What mechanisms does the family have to access a trusted talent pool outside the family?

In a world where family members are increasingly spread out, developing an Attachment Strategy is a key tenet of longevity.

We find that family values are transferred – both within the family and the community – orally, by coming together during festivities, family and business events, often living close to each other in the community, through practices of storytelling and sharing anecdotes about the family and business history. In most instances, the family members reported that the role of key family members is central in creating this sense of attachment and belonging. But crucially, they also admitted that these practices emerged without a formal or intentional process. For instance, in one family-owned business, the family has a tradition of sitting around an old table, which is estimated to be from the first generation of owners. The table as an artefact steeped in the history of the family business creates a bond – a sense of attachment. We find that in a world where family members are increasingly spread out, developing an Attachment Strategy is a key tenet of longevity.

While attachment and reputation strategies may use similar practices, the outcomes are quite different. Where attachment creates a sense of belonging with the family and the community, reputation creates a sense of pride and duty.

Longevity is not so much about emulating the practices of the most successful family-owned businesses, as it is about understanding the outcome of these practices and designing them along the pillars of the DREAM framework.

Finally, our research indicates that families in businesses that lived beyond 100 do not put the motive of profit-maximisation first. Instead, they consider long-term growth. They set aspirations, for both the business and the family, that emotionally motivate individuals to coalesce around a vision. We call this Motivating Aspirations.

Figure 1: The DREAM Framework

Source: © LIVING BEYOND 100 – Bhalla and Banerjee

We see these five pillars together as the core to the long-term development of family-owned businesses. The DREAM framework is a starting point in understanding priority areas (Figure 1). It takes time, a focused approach and leadership commitment for developing each of these pillars. There is no short-cut! While our research identifies several best practices that these five British businesses follow, we find that these practices are unique to the context of those family-owned businesses. Every family-owned business must, therefore, find or design the set of practices that work for it, within the context of their community. Therefore, longevity is not so much about emulating the practices of the most successful family-owned businesses, as it is about understanding the outcome of these practices and designing them along the pillars of the DREAM framework.