The concept of ‘smart cities’, as a means of providing enhanced and improved quality of life, is gaining acceptability rapidly. The celerity of advancement in information and communications technology (ICT) is the main driver of this improvement. Growing convergence of ICT and conventional technologies is a major enabler that gives rise to such smart cities. The resultant automation of monitoring, controlling and executing has the potential to greatly empower city management and augmented capability, to provide vastly improved services to its denizens. However, owing to the primacy of the role that ICT plays in the construct of a smart city, most related discussions tend to be severely skewed towards this technology component. Without detracting from the importance of technology’s role, it needs to be borne in mind that technology can function only in a context and the context of every city is unique to itself. Implementing technology without adequate consideration of other related factors would render the initiative futile. Gaining an intimate appreciation of the context is, therefore, quintessential to successful establishment of ‘smart cities’.

Urban agglomerations are often, if not always, formed in response to either economic and/or locational factors. Some cities are formed because of proximity to sources of raw material, skills, or markets while some are located centrally and are therefore ideal for a specific purpose, say administration. All subsequent aspects of the city are determined by the choice of the activity (economic or otherwise) that the city has been formed to address. In most cases, smart cities are being created from existing ‘unsmart’ ones. In other words, there already exists one or more economic activity that the city is engaged with and is most likely to continue. This then becomes the raison d’etre for the smart city. In the case of greenfield cities, the city fathers may choose one or more economic activity and mould all aspects of the city around that. Based on the accepted and articulated economic activity, subsequent aspects of the city will be specified. This will strongly impact the selection of supporting ICT as well, in a significant manner.

Consider a city that is located centrally and is, therefore, a hub of markets. One has markets for different products where buying and selling in large quantities take place. The needs of such a city will centre around handling a large floating population that come with their produce, that may need to stay overnight at times, whose evenings may be free, that may need help in carrying goods from one place to another. Many trucks and vehicles carrying goods will be coming in, going out and even passing through such a city and so on. Concomitant ICT systems would be aimed at enabling satisfaction of those specific needs. For instance, internet and Wi-Fi connectivity has to be very strong, making available accurate information on products and services in markets across the world, and support working on deals with partners from remote locations. Adequate safety and security systems need special attention, owing to the mix of the floating and fixed populations and so on.

Urban agglomerations are often, if not always, formed in response to either economic and/or locational factors. Some cities are formed because of proximity to sources of raw material, skills, or markets while some are located centrally and are therefore ideal for a specific purpose, say administration.

Contrast this with the ICT requirements of a city whose main activity is education, where students from various places come to pursue their studies, where counsellors and sports facilities are very important, where students’ accommodation facilities need monitoring as do the standards of education, the quality of faculty, etc. A moment’s reckoning will reveal that the ICT requirements would vary between these contexts as they would for other contexts as well. Naturally, a major part would be common but the nature of those systems would also be determined by similar contextual factors. Existing literature on this subject appear to suggest that all smart cities ought to have similar, if not same, systems like automation of traffic, healthcare, water and electricity distribution and so on. However, as the earlier part stresses, precise needs would be derived once the basis for the city is understood.

Secondly, no city, and definitely not a ‘smart city’, can afford to exist economically or socially sequestered from the physically contiguous areas in which it is resident. The smartness of a city will perhaps be difficult to endure if it is an island of prosperity in a sea of poverty. The economic activity chosen for a city would be best served if it is tightly integrated with those of the hinterland. Additionally, a close liaison with the monitoring and governance systems of the neighbouring areas would be safety and security measure of the city itself. This link will necessarily be greatly facilitated if the ICT systems are adequately integrated and that is an important requirement of such smart cities. While a surfeit of literature is routinely generated on smart cities, I have not seen this particular point being highlighted anywhere. In fact, smart cities as a present day initiative can well be viewed as a crucial opportunity. Smart cities could well be drivers of economic growth in the neighbourhood of their existence if these are cleverly integrated. In fact, the potential for a city to develop its hinterland may be a good criterion to selection of cities under this head.

A third requirement that is not so commonly discussed about ‘smart cities’ in current literature, is the real time participation and education of its citizens. Currently, citizens are not used to the various aspects of smart cities, and a continuous availability of information or education about different features of the smart city may have to be made available to elevate residents and users to ‘smart citizens’. In addition, a continuous feedback of services and difficulties, followed by action taken will definitely aid in augmenting services. ICT is perhaps the main plank that can effectively support such dissemination of information and provision of a feedback path to the local authorities.

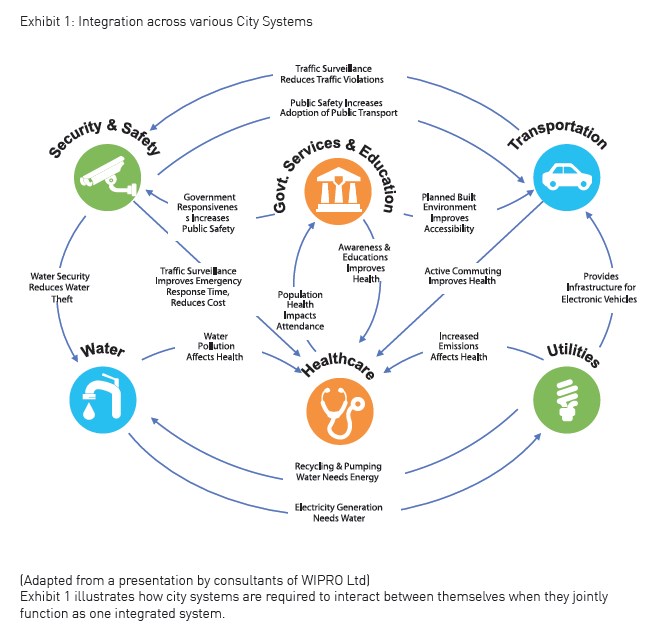

ICT, as mentioned earlier, is the main enabler of smart cities and currently there are clear ideas about how such enabling will take place. We have presented these three requirements, that we assessed forms the context, which will inevitably impact the performance of the city on all critical counts. Adequacy of services relating to four pillars of social, economic, environmental and governance will be adjudged on the extent to which related services meet expectations in this context. A city is essentially a network of networks. There are several networks that exist in a city and collectively they furnish all the services needed by the citizens. Transport, roadways, education, traffic control, safety and security, and so on can each be visualised as a collection of information resources that service the customer as required. They function in a relatively autonomous manner, but being parts of a whole are required to jointly function as well.

ICT provides the backbone for this integration and this integration will come into play when occurrences or events that require such joint functioning for fulfilment of immediate needs arise. For instance, if a water pipe has burst, or a fire has broken out at 2 p.m. and schools get over at 3 p.m. we need an information to go, probably from the roadways system, to the school buses to adopt a different route today. The roadways system gets the information from the water distribution system and takes action as may be required. As we all understand these functions are actually connected but often, owing to our approach and working styles, we tend to view these in isolation. Organisation of work is often such that we are constrained to work in silos and, therefore, miss these inter-linkages that are inherent to the functioning of these networks. Touch points between the various networks will have to be identified at the time of design, but this onetime exercise will not suffice and a regular process to identify and incorporate these integration points needs to be designed and implemented. In fact, this too can be automated thereby rendering a city as a self-learning system. From the perspective of ICT this is a major capability that truly renders a city smart, and should therefore be actively pursued. Cases where exceptions to the rule occur require investigation to identify new relationships, that may have emerged and which need incorporation in existing systems.

The smartness of a city will perhaps be difficult to endure if it is an island of prosperity in a sea of poverty. The economic activity chosen for a city would be best served if it is tightly integrated with those of the hinterland.

The ICT systems in a smart city can be designed to be effective self-learning systems. Intervention points would necessarily have to be incorporated so that the course of action on the occurrence of events that require two or more networks to function in tandem are specified. With experience the repertory of interventions can be updated with newer occurrences. For example, if there is a power outage the system will immediately be aware of this occurrence. There could be say, four reasons why such an outage may happen. First, it could be a sudden increase in demand that results in a fall of the frequency triggering off the low frequency protection and thereby halting the machine. Second, it could be because of snapping of a cable, third, a short circuit in the downstream equipment, and fourth, a malfunctioning of the generating equipment. Now, all these are monitored parameters in different systems and being integrated with the main system would immediately reveal the cause of the outage. While the ICT for each of the networks would naturally exist, it is such an integration that will ensure that the various limbs are working to meet city-wide objectives.

Self-learning systems are a valuable capability that can be designed into smart ICT systems and thereby engender higher levels of automation. A city where neither an external control is required nor is an internal centralised control required but where all activities are executed through a distributed Organisation and a corresponding level of empowerment would constitute a self-organising city. Consider natural processes that are completely self-organised without any centralised controls and the regularity with which these are done. Take the rain cycle where every year without fail we witness the ‘evaporation to precipitation’ process playing out to yield rain. Who controls it? No one, and yet it functions with exemplary regularity. Ideally a smart city too, bolstered by properly designed ICT, and a corresponding distributed work Organisation can, legitimately, aspire to being a self-organised in management of the city. In fact a city, to be really smart, has to be a self-organising one. Both selflearning systems and self-organising cities are legitimate objectives of smart cities.

There is no gainsaying the fact that smart cities are technology-based but that does not completely define them. Technology is aimed at achieving a higher level of services enjoyed by citizens and, therefore, is a means to an end rather than an end by itself. If designed and implemented properly it has the potential to integrate activities of the city such that the latter functions as one entity and not a collection of disparate elements. However, it needs to be equally borne in mind that this technology without concomitant modification to strategy, structure or systems will not yield results that are being sought.

Touch points between the various networks will have to be identified at the time of design, but this one-time exercise will not suffice and a regular process to identify and incorporate these integration points needs to be designed and implemented.

The ICT Construct

Objectives that need to be pursued in the making of a smart city have been discussed earlier. The next pursuit is to determine the broad characteristics and components of the ICT systems that will support the achievement of stated objectives. A city is multi-faceted and has several constituent systems that collectively deliver. These systems have extensive overlapping areas and at any point in time a multi layered delivery mechanism is in operation. Traditionally the focus has been on the output of a specific system thereby delivering services that need integration at the consumer level. This sub-optimal delivery is unsatisfactory and not ‘smart’ at all. The ICT mechanism constitutes the nervous control system of the city and has the potential to elevate the city’s functioning. Through a properly designed ICT system the various constituents can be integrated and the city can operate as one entity and not a mere collection of sub-systems. In the case of smart cities the requirement of integration extends to the neighbouring areas as mentioned. A truly integrated system will enable the smart city to be instrumental in the development of the neighbourhood. The ICT systems have to cognise with this link in addition to the interconnected city systems.

A city is multi-faceted and has several constituent systems that collectively deliver. These systems have extensive overlapping areas and at any point in time a multi layered delivery mechanism is in operation.

Critical Features of Smart City Systems

A smart city, in order to fulfil its potential needs to have certain features and capabilities that could enable desired levels of delivery, would have a detailed apparatus for collecting and aggregating data on assets and processes. This would include sensors, actuators, cameras, and other instruments, along with data aggregators. These would jointly receive and send data to back-end systems. The heterogeneity of the sources will necessitate integrating applications that have the capability to collect this data and pass it on to the specific destination(s) as may be required by the process, irrespective of the source of the data.

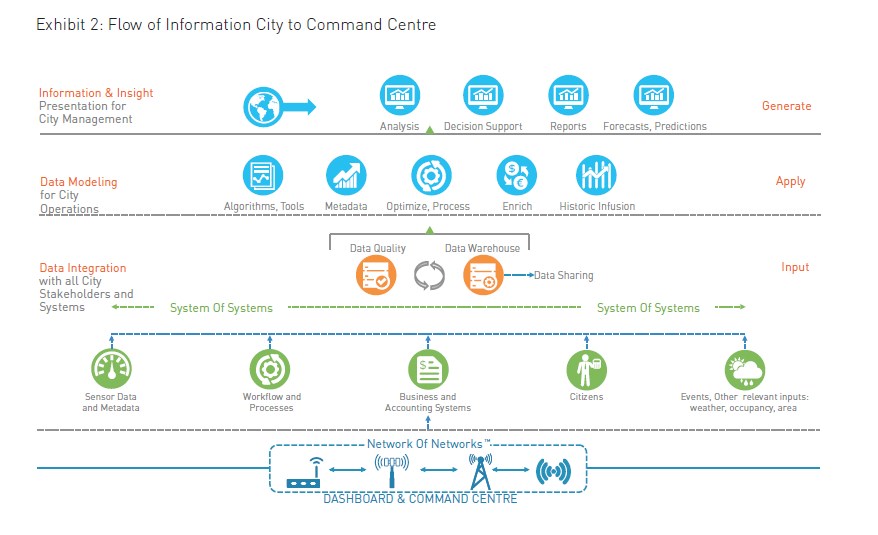

Transactions based on such exchange of data will naturally get precedence and this entire process will help enable delivery of services in a quick, transparent and reliable manner without human intervention. Interactions that citizens have will be greatly enriched as and when the digital and physical spheres of activity are brought closer to each other engendering a truly inclusive ambience. Information regarding the process can be transmitted to officials, if required, or in the event of exceptions that may arise from time to time. Learning capabilities will be built into these and other applications, where correlations between factors or events will be incorporated to decide based on such relationships. Exhibit 2 below gives a snapshot of information flow in this context, to the central command centre.

Testing or trying out various options will not always be possible and the need to simulate conditions will be an absolute necessity and hence the corresponding ICT systems would be required.

Post transaction, activities will centre on data analytics and decision making so as to enable databased rather than ‘gut-feel’ decision making. This will greatly improve quality and openness of decisions, and support a proper governance mechanism for the city. Another critical activity that extends well beyond transactions is a platform for continuous exchange with citizens. ICT systems augmented by suitable platforms would support such bi-directional exchange. While this can be used for a variety of objectives, education and capability building of citizens as well as feedback to guide the forward path will surely be the most critical component. A critical piece of information that would help city authorities to provide better services would be to understand how information furnished by systems is actually being used.

An important functionality that managing smart cities will surely need is the ability to simulate and test various options. Testing or trying out various options will not always be possible and the need to simulate conditions will be an absolute necessity and hence the corresponding ICT systems would be required. This is very important for, inter alia, the safety of citizens.

Deriving from the overall objectives enumerated above, integration of various facets of the city’s functioning is a sine qua non. As mentioned, intelligent integration will facilitate achievement of those stiff aspirations that smart cities are being entrusted with. Such integration will be enabled by adopting an open and common information model for both information and communications technology. Leveraging common infrastructure supports creation of such integrated systems that seamlessly communicate and join hands to complete a transaction, or furnish insight as may be required. This common information model is also a more economic proposition since it is scalable with reducing marginal costs.

Data centres, back-end platforms, analytics, etc. will comprise this critical element of a smart city’s ICT landscape. This will provide support for data acquisition and processing platforms, such as M2M and big data, shared resources for collection, storing and processing of data…

ICT Pillars of Smart City

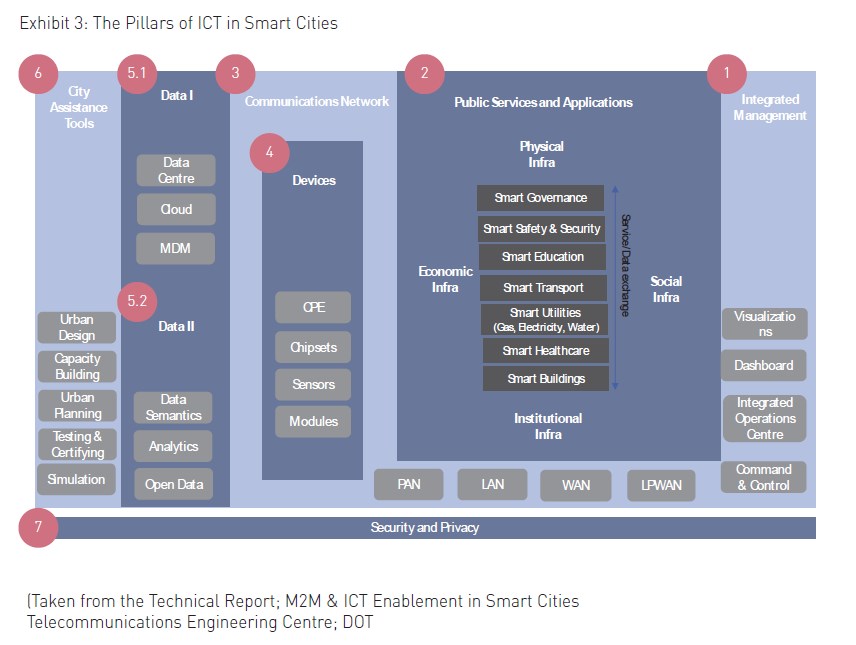

In a report titled “Technical Report’ M2M & ICT Enablement in Smart Cities by the Telecommunication Engineering Centre of the Department of Telecommunications, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Government of India, seven functional pillars have been identified that comprehensively present the ICT landscape required in a smart city. Exhibit 3 pictorially depicts these seven pillars.

a. Integrated Management and Command Centre: While command centres for functionally or geographical areas may exist, this central command centre will display the output for the entire city. Adequate level of integration will ensure a comprehensive view of the city in such a command centre.

b. Public Services and Applications across verticals and their Integration: Applications that furnish individual services such as mobility, healthcare, utilities, governance and others, along with the intelligent integration, will constitute the list of applications that will support transactions and a well information reporting.

c. Communications Network: This comprises networking technologies and forms the infrastructure of smart cities that will provide the highway on which information will flow. There will be a combination of technologies and protocols for this, including wired, wireless, low power networks and others.

d. Devices and Chipsets: This will be made up of a large number of devices including routers, computers sensors, chipsets, mobile devices, embedded software, etc.

e. Data: Data centres, back-end platforms, analytics, etc. will comprise this critical element of a smart city’s ICT landscape. This will provide support for data acquisition and processing platforms, such as M2M and big data, shared resources for collection, storing and processing of data, and other similar elements required for the city’s management. In addition to the above it would include enabling data analytics to support and facilitate data-based decision making that is known to be more effective than others.

f. City Assistance tools: ICT tools for urban design, simulation, testing and certification as well as capability building make up the sixth component in this list. It will furnish supporting mechanisms that enable these functions.

g. Information Security: This is perhaps one of the most important elements of the ICT systems. It would cover end-to-end processes as well as privacy issues that such systems are definitely going to throw up.

Conclusion

Smart Cities have engendered a level of interest not seen earlier in infrastructure projects. The potential they hold is enormous, provided we design all related systems holistically considering variety of objectives and holding high the targets. In this article the attempt has been to present a few ideas that are not commonly discussed in the context of smart cities, and present an outline of corresponding ICT systems.

REFERENCES

Saraju P Mohanty, Uma Choppali and Elias Kougianos., “Everything you wanted to know about Smart Cities” ResearchGate; July 2016

Peter M Allen., “Cities and Regions as Self-Organizing Systems: Models of Complexity” ; International Ecotechnology Research Centre; England; 1994

Technical Report, M2M & ICT Enablement in Smart Cities;TECTR- S&D-M2M-006-01 Telecommunication Engineering Centre;

Department of Telecommunications; Ministry of Communications and Information Technology; Government of India; 2015

TSDSI Publication; “Smart Cities- An overview of the role of Information and Communication Technologies in the Indian Context”, TSDSI-M2M-TR-SmartCitiesICT; 2015