The 21st century has seen profound technological innovations with developments like automation and artificial intelligence (AI) making new forays into the industrial processes. With the world innovating at such a breakneck speed, no country wants to be left in the lurch. As this author has argued elsewhere (2018):

Most significantly, China has laid out a plan to become an “innovative nation” by 2020 and an “international innovation leader” by 2030 in its current Five-Year Plan.1 Even resource-dependent countries like Saudi Arabia are making a conscious move towards greater innovation.2 These countries are beginning to recognise the fact that building a competitive advantage based on factor endowments (cheap labour in the case of China and oil reserves for Saudi Arabia) cannot be sustained in the long run.3

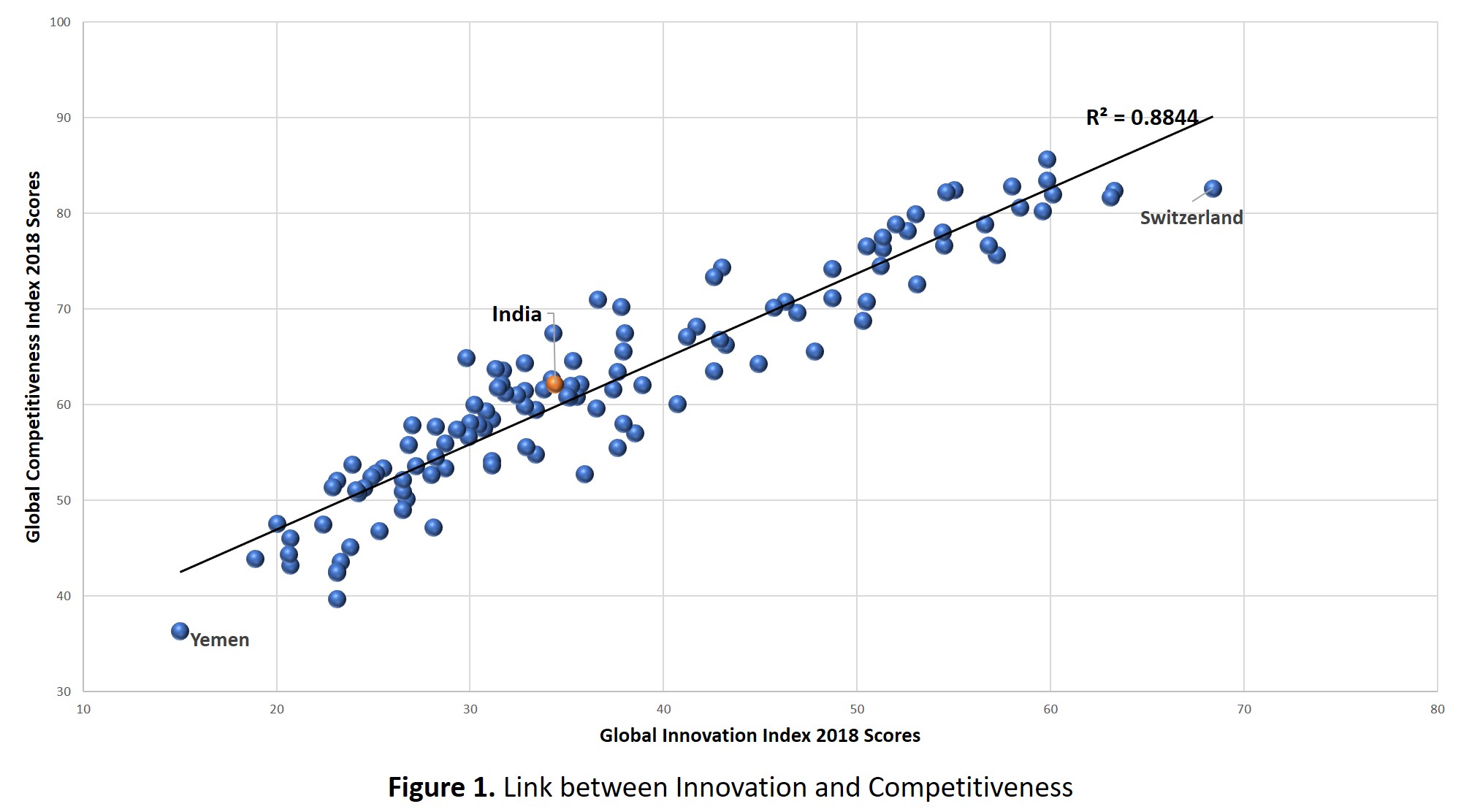

A transition to a knowledge-based economy with greater emphasis on innovation to drive economic growth and competitiveness is imperative to move out of the middle-income status.4 In fact, there is irrefutable evidence that the competitiveness of a nation, or the productivity with which it utilises its resources, is highly correlated to its level of innovation. A country’s competitiveness is defined by the World Economic Forum as “the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country”.5 Increased productivity leads to growth, resulting in improved income levels which in turn translates into greater well-being.

When firms innovate, they derive prosperity by creating value-adding products through efficient utilisation of their resources. This ability to innovate increases their productivity and in turn, enhances their competitiveness. So, innovation should be considered as the basis for creating prosperity.

Recognising the importance of innovation in enhancing the competitiveness of nations, the Global Innovation Index (GII) was constructed by researchers at Cornell University, INSEAD and the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) to provide detailed metrics about the innovation performance of 126 countries. These nations represent 90.8% of the world’s population and 96.3% of global GDP. Its 80 indicators explore a broad vision of innovation, including political environment, education, infrastructure and business sophistication.6

The Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) published by the World Economic Forum, on the other hand, ranks countries based on 12 pillars of competitiveness including infrastructure, ICT adoption, macroeconomic stability, skills, product market, labour market, financial system, market size, business dynamism and innovation capability, to mention a few. It emphasises the role of human capital, innovation, resilience and agility as not only drivers but also defining features of economic success.7

Figure 1 shows the link between competitiveness and innovation at the global level using the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) and the Global Innovation Index (GII) scores of over 120 nations. The coefficient of determination between the two turns out to be a high 0.88.

Source: Global Competitiveness Report 2018 and Global Innovation Report 2018

I have suggested elsewhere (2018):

Considering the importance of innovation in the progress of a nation, India cannot afford to lag behind in the race of innovation. The country failed to benefit from the first industrial revolution due to its colonial past. It is, therefore, a rare opportune moment for India to accelerate its development process and move into the next stage of growth by focusing on strategies to foster its innovative capacity.3

The first half of this article concentrates on an assessment of India’s performance in the Global Innovation and Competitiveness Indices, through comparison with other countries. The subsequent sections reflect on the innovation landscape in India across sectors and regions, finally culminating with some policy recommendations that can help augment innovation and herald economic prosperity.

The Innovation Environment in India

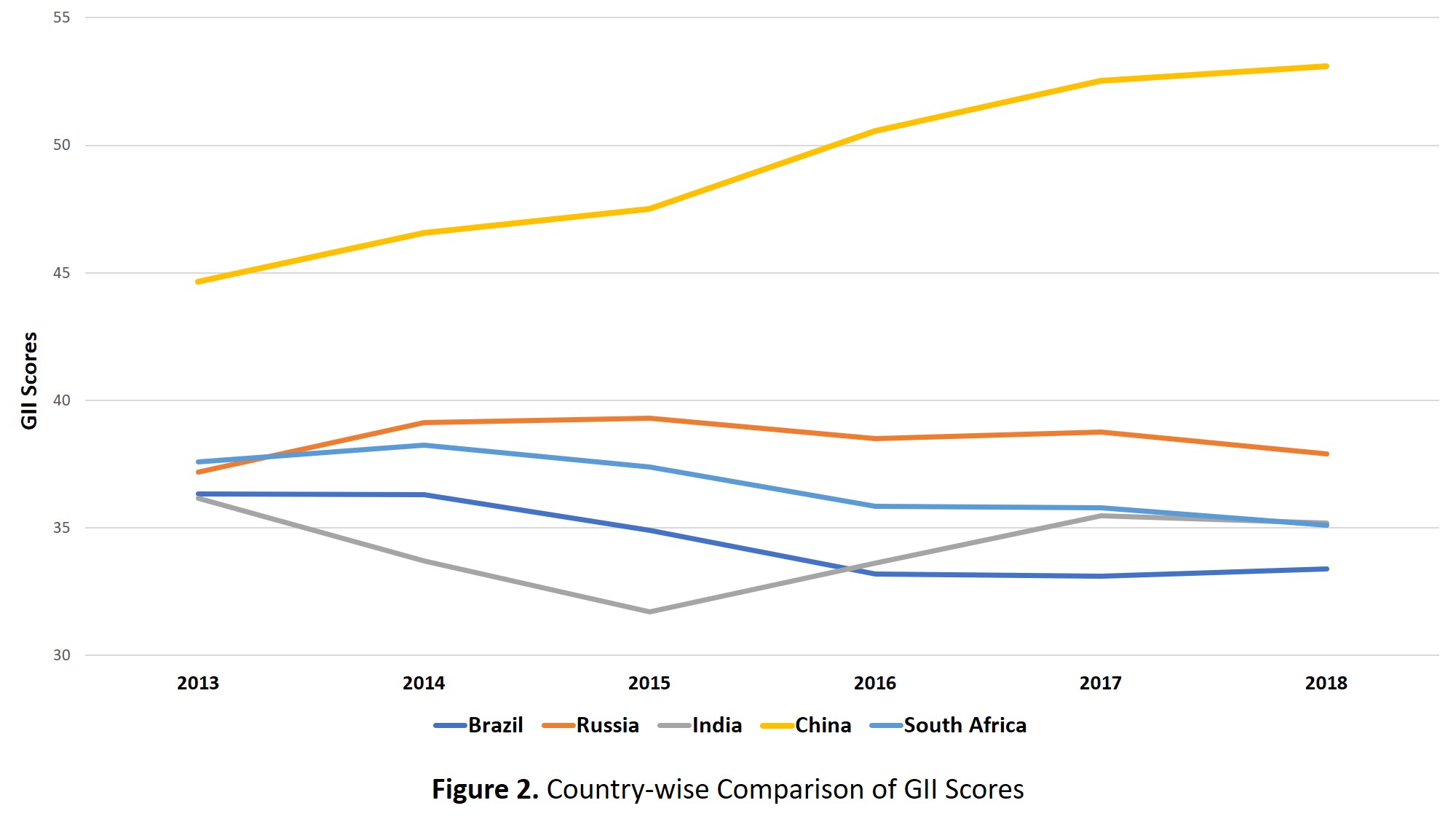

India’s performance on the innovation front has not been historically promising, as revealed by the trends in the Global Innovation Index (GII). In GII 2018, the country ranked 57 out of a total of 126 countries. Figure 2 shows the performance of the BRICS nations — (Brazil, Russia. India, China and South Africa — between 2013 and 2018. It is quite apparent that India has been the worst-performing nation of the group for a large part of the period and has only managed to better Brazil recently. In fact, until 2015, India’s scores fell quite drastically, which explains why its recent scores are hardly different from those in 2013.

Source: Global Innovation Index Reports

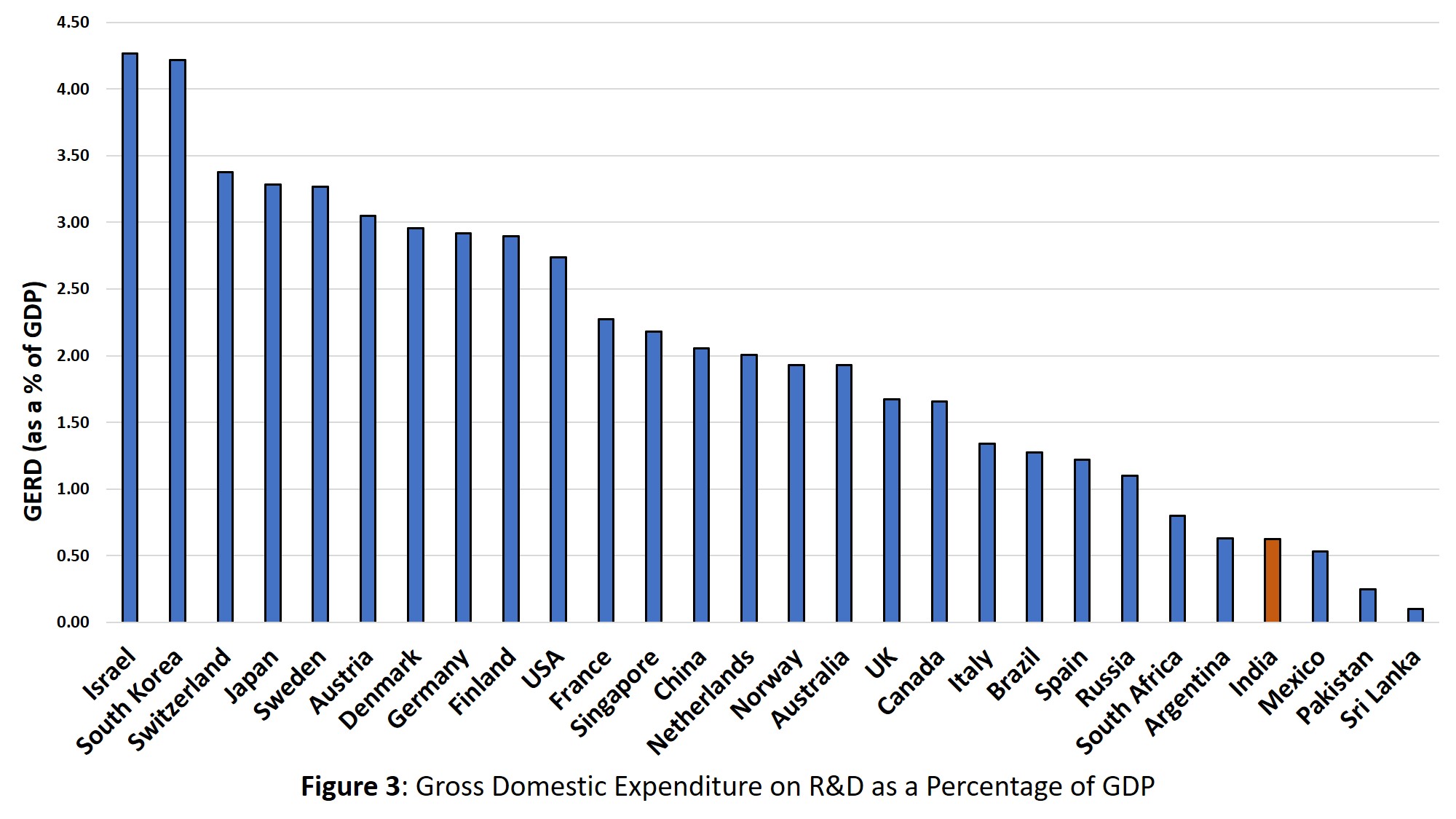

Why is India’s performance so lacklustre as compared to the other countries? To begin with, as compared to the rest of the world, India devotes only a small percentage of its total expenditure to research and innovation. India’s gross expenditure on Research and Development (R&D) as a proportion of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has consistently fallen in the last decade after reaching a peak of about 0.85 and has now settled below 0.7.8 This is very low in the global context as can be seen in Figure 3. Again, among the BRICS nations, India spends the lowest on R&D.

Source: UNESCO 2015

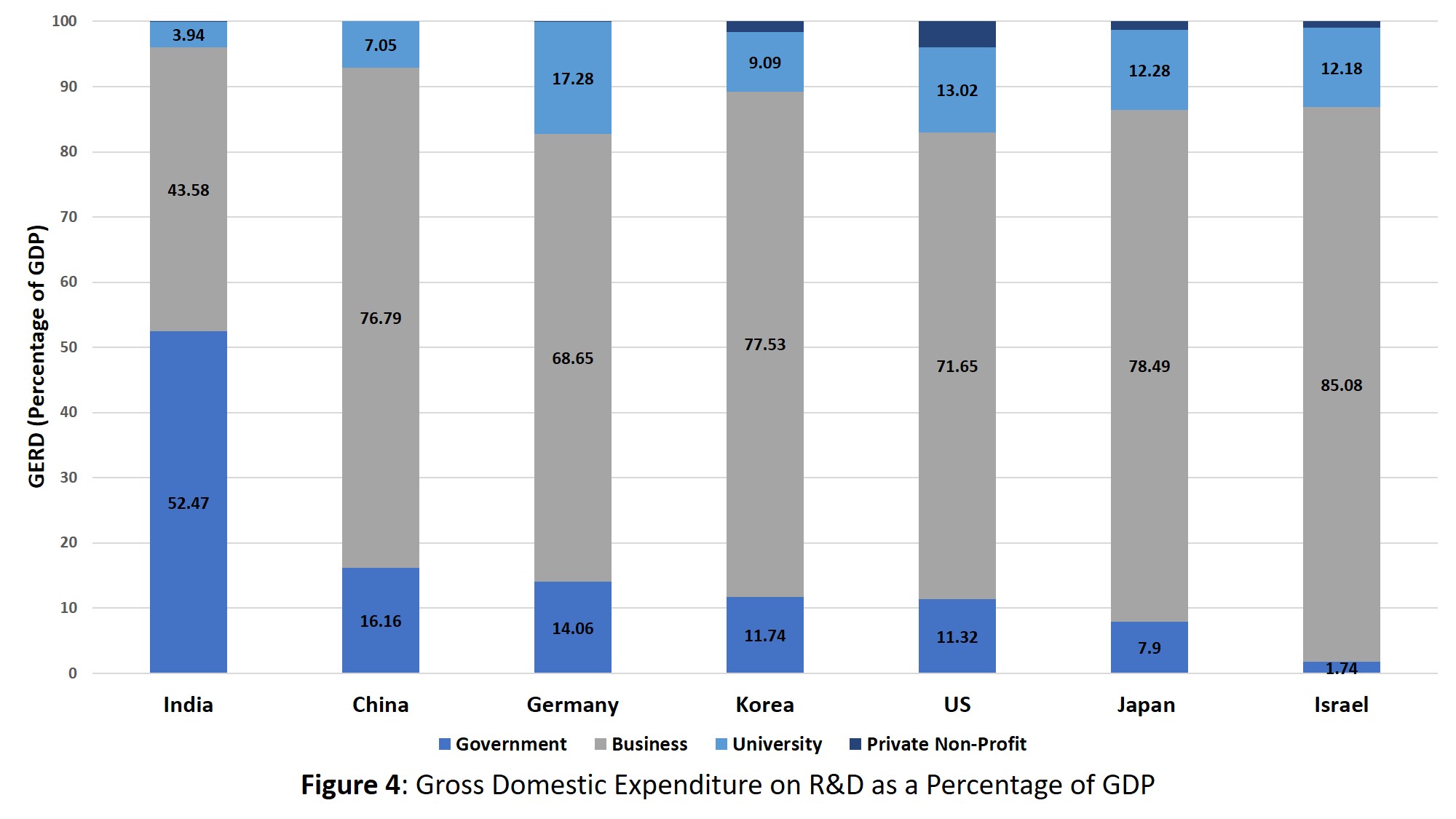

Curiously, it is not the government but the private sector that is holding back the expenditure on R&D. Compared to the global spending patterns, the private spending in India towards R&D is seriously lacking as illustrated in Figure 4. Compared to 77% in China, the share of private expenditure going towards R&D in India is merely 43.5%. Clearly, India is failing to provide the enabling conditions for adequate private investment in innovation.

It is not the government but the private sector that is holding back the expenditure on R&D. Compared to 77% in China, the share of private expenditure going towards R&D in India is merely 43.5%.

As far as the number of researchers is concerned, India presents a worrisome trend as well. The country had about 216 researchers per million people in 2015 while the world average had already crossed 1277 in 2010. At the other extreme, countries like Israel had over 8255 researchers per million. Thus, the Indian innovation ecosystem is at a very nascent stage.9

However, in such a vast landscape, it would be a mistake to make sweeping generalisations. India did achieve excellence in sectors like the pharmaceuticals, automobiles and Information Technology (IT). More than half of the business R&D expenditure is distributed across just these three industries. These are also the fastest-growing sectors in India, making significant forays into the world market.10

Innovation at the Sub-National Level

Just as the innovation ecosystem in India varies across sectors, Indian states present similar disparities. Across the globe, there are some regions which have been more creative and innovative than the others. The key is to identify factors that enable innovation and to then leverage them to build regional competencies and drive competitiveness.

One of the common ways to assess the innovation ecosystem across regions is through the number of patents filed. Using patent filings as a proxy for innovation suffers from limitations. Whenever patents are filed by businesses, they are done from the location of the company headquarters instead of the place of innovation. Hence the number of patents cannot capture the full extent of innovation taking place in a country. Nevertheless, despite all its imperfections, it is one of the best proxies for innovation.

Based on data from the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DIPP), it can be concluded that patent filings are highly concentrated around southern and western India with Delhi being the only outlier. The latter has the highest number of patent filings per lakh of population followed by Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Telangana. This is because the major Indian cities of Delhi, Mumbai, Pune, Bangalore, Chennai and Hyderabad which are the leaders in innovation are located in these states.

The country had about 216 researchers per million people in 2015 while the world average had already crossed 1277 in 2010. At the other extreme, countries like Israel had over 8255 researchers per million.

The rest of India seems to be seriously lacking. In absolute terms, while Maharashtra filed about 3600 patents in 2016-17, Uttar Pradesh, a state that dominates the former in terms of population, filed merely 637 patents. Surely, such high levels of disparities cannot be attributed to factors like skewed location of company headquarters. States like Uttar Pradesh are simply unable to provide enabling conditions for greater innovation. Be it human capital, policy, infrastructure or funding – the drivers of innovation are weak across most Indian states.

One of the most basic conditions that sets the wheels of innovation in motion is the availability of human capital. Silicon Valley, for instance, stands out because of the presence of world-class research universities like Stanford and the University of California – Berkeley in its vicinity. Similarly, in India, innovation gravitates towards states that manage to produce a healthy supply of human capital.

To assess the performance of Indian states on human capital, an aggregate of a set of three indicators is taken: number of students in engineering and technology per lakh of population, number of full-time researchers per lakh of population and the pupil-teacher ratio in higher education.

Based on this measure, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Delhi, Telangana and Karnataka form the top five states with respect to human capital. Apart from Maharashtra, these states file the highest number of patents as well. Once regions have an adequate supply of human capital, the next inevitable enabler to drive innovation is the provision of commensurate infrastructure.

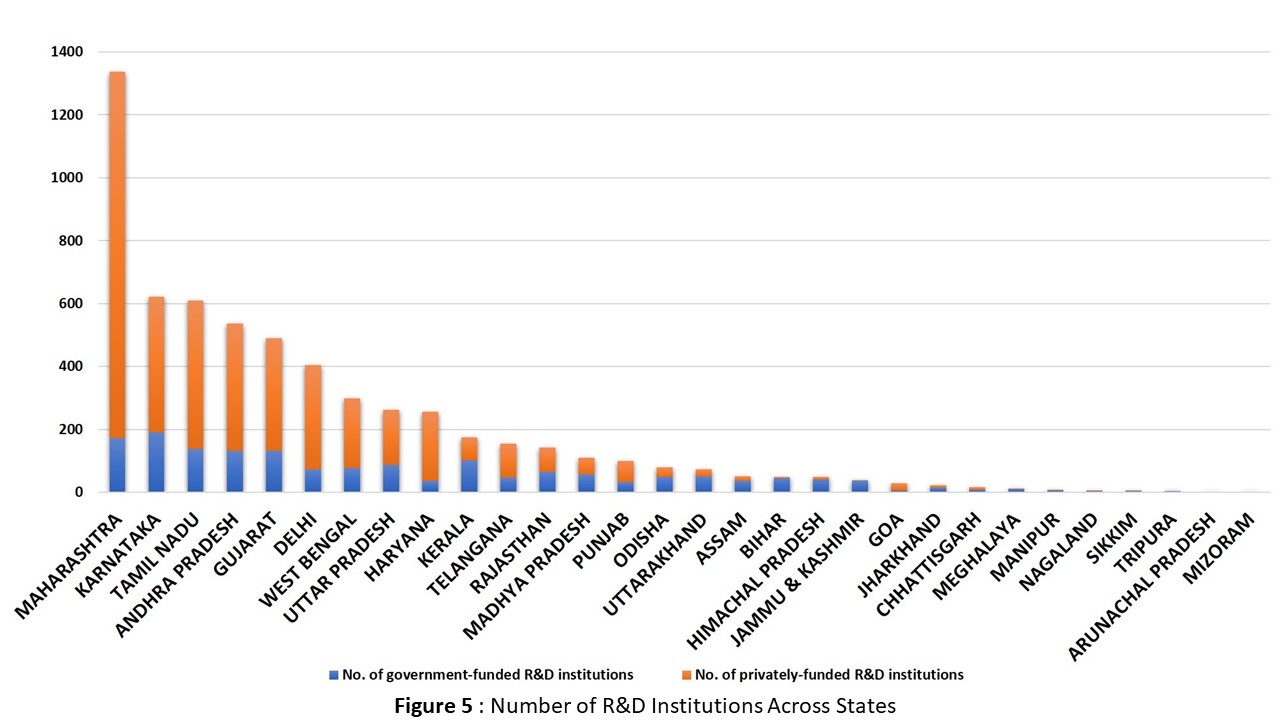

Figure 5 puts this in perspective. It shows the number of research and development labs set up across states as of 2018. This includes both government-funded and privately-funded labs. The typical southern and western concentration is evident from the figure. With greater availability of human capital and prevalence of research labs, i.e. greater investment in research, innovation is bound to concentrate around these regions.

Source: Department of Science and Technology (2018 Data)

Parallels with China

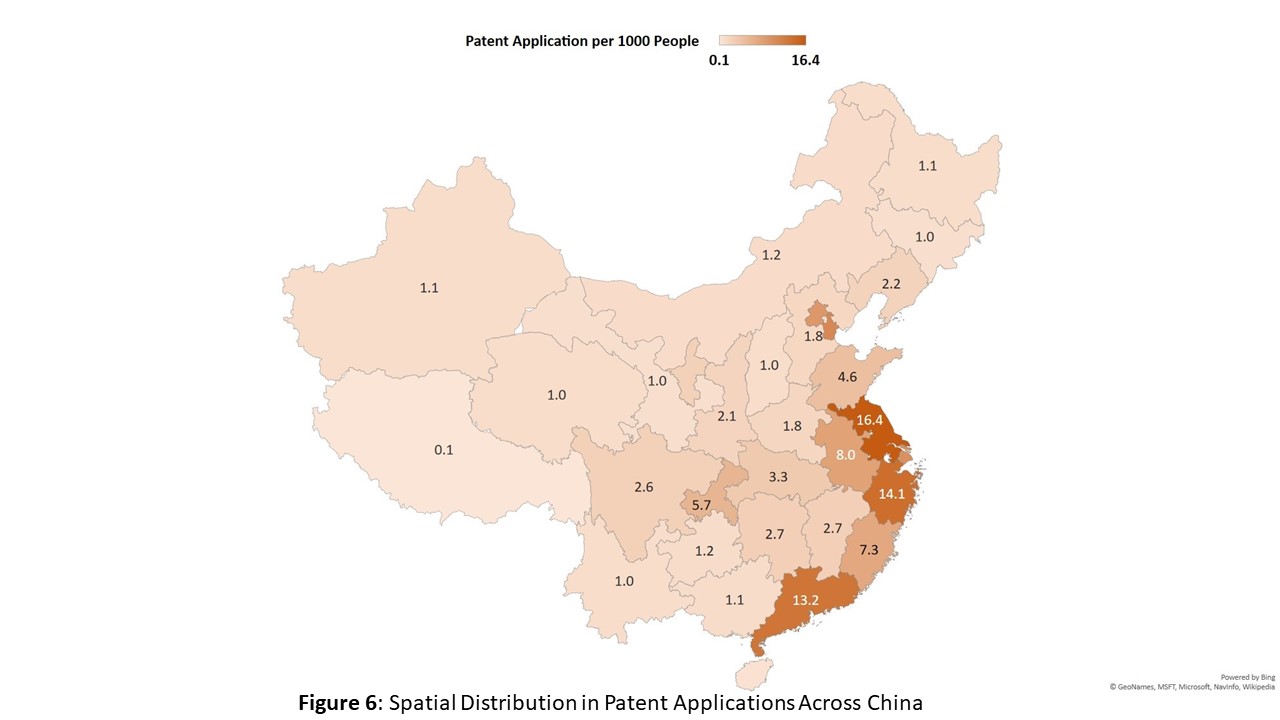

India is not unique in the regional spread of innovative capacity. China also displays a similar spatial distribution with respect to innovation. Figure 6 shows how patent applications in China are highly concentrated in coastal areas. Innovative activities are much less intense in the western inland regions. This trend is very much akin to India, where patenting activities are significantly concentrated in the southern coastal states with the only exception of Delhi.11

Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Delhi, Telangana and Karnataka comprise the top five states with respect to human capital. Apart from Maharashtra, these states file the highest number of patents as well.

Incidentally, the top three Chinese provinces registering the highest number of patent applications – Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang – account for about half of the country’s patent applications. Likewise, the top three Indian states by number of patent application – Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka – account for more than 56% of the country’s patent applications.

Therefore, regional disparities in innovative activity experienced by India seem to be a general trend in emerging economies around the world. In contrast, the geographical spread of patenting activity spans more regions in developed economic blocs like the US and EU.

Source: China Statistical Yearbook 2017

Policy Recommendations

This, however, does not imply that the lesser innovative regions in India remain complacent about driving their innovative capacity. To begin with, India needs to improve its spending on R&D if it aims to be an innovative economy.

Coming to more specific concerns, there remain multiple challenges with the Indian education system. First, the education system is not industry-oriented and hence produces students with low employability, forcing industries to give them months of intensive training to improve their productive capabilities. Secondly, the focus of the Indian education system is on quantity — the numbers of hours taught — rather than on the quality of education imparted. As a result, the human capital produced by the states is hardly satisfactory to cater to global innovation standards. Even though India produces the highest number of engineering graduates in the world, a study by Aspiring Minds on the programming skills of Indian engineers found that only 1.4% of them could write functionally correct and efficient code.12

In order to resolve this challenge, industry and academia need to work together to design syllabi and curricula to enhance the employability of graduates. Also, the focus of universities should be on the quality of education imparted by the professors rather than the time spent with students. This will improve the quality of human capital while ensuring the professors have more time to focus on their research.

Even though India produces the highest number of engineering graduates in the world, a study of the programming skills of Indian engineers found that only 1.4% of them could write functionally correct and efficient code.

A second challenge that needs to be considered pertains to industry-academia linkages. Indian universities tend to work in silos and their lack of synergy with industry results in research that has little commercial value. There is also a lack of clarity on ownership of intellectual property rights on innovations resulting from the collaboration between industry and academia. To encourage greater innovation, such issues need to be addressed.

Finally, states that are lagging in innovation need to draw inspiration and insights from their southern counterparts and begin working towards addressing their deficiencies. Only governments can enable conditions for greater innovation. Therefore, they need to provide determinants like adequate human capital, proper infrastructure and attractive opportunities for businesses within their regions. Only by working along these lines can India drive innovation and further prosperity.