Doctoral education in management in India is in crisis1. There are about 4,000 business schools in India today, with estimated faculty strength of 30,0002. While a few hundred schools may have recently shut down, the available data indicates that the number of management institutes in the countr y is growing at a compounded annual rate of about 15%. These schools collectively have the approved capacity to offer postgraduate degrees in management to about 350,000 students ever y year. If the All India Council of Technical Education (AICTE) mandate to maintain a student to faculty ratio of 15:1 is taken seriously, and assuming a two-year programme, then we are already looking at a shortfall of about 16,000 faculty members. The AICTE norms for faculty positions at management schools also require that professors and associate professors together make up a third of the faculty strength and that they should all have PhDs (or equivalent qualifications). Thus, there is no dearth of demand for management faculty with PhDs.

Rather, the problems lie on the supply side. The country has about 500 doctoral programmes spread across various universities and institutes of national importance. Together, these produce well under 1,000 PhDs in management and allied topics in a good year (there are normal year-to-year fluctuations in doctoral programmes worldwide). I suspect that even more critical than the shortfall per se, may be the danger that it will be met, at the expense of quality (and perhaps after wasting significant resources). This, therefore, seems an opportune time to stop and reflect on the purpose of a doctoral programme in management and on the future of doctoral education in India in particular.

In this essay I argue that the resources invested in doctoral education in management could be invested more effectively if we recognised that there are in fact multiple possible objectives for doctoral education in management, and that achieving each requires different kinds of investments. As a corollary, it follows that not ever y institution need offer all kinds of doctoral training. I conclude by noting that India could well play a pioneering role in developing the implications of this idea.

Background … and an Important Disclaimer

The dominant model of a research-based business school in the developed world owes its origins to the ideas of the Nobel laureate Herbert Simon and his colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University. These pioneers set out to construct a business school that attempted to marry the rigour of basic research in the (social) sciences with applied knowledge from the domain of practice3. For a polymath with remarkable organisational skills like Simon, the task may not have seemed insurmountable; yet, as Simon himself famously recognised, keeping the two epistemic communities of research and practice mingling constantly in a fruitful manner rather than separating out would require enormous and constant administrative effort. This, in a colourful analogy, he likened to the effort required to keep an oil and water emulsion from separating.

To what extent the oil and water have remained emulsified is a topic of keen debate and discussion among the top business schools in the world today4. The situation has become a lot more complicated since Simon’s initial statement, at least in part because of the growth of doctoral programmes in business schools that increasingly produce faculty members with skills comparable to those in the older noted above are really challenging the continued importance of scientific research in management; indeed, many of the critiques can be read as deploring the insufficient importance given to the scientific method by researchers who lose sight of the centrality of understanding phenomena in their desire to cast it into a particular disciplinary viewpoint6.

Thus, my arguments below do not involve a rejection of the critical role of scientific research (and by extension, of doctoral training in scientific research) in a business school. Rather, my arguments are that: a) producing researchers is not the only possible role for doctoral training, and b) that there are new ways of delivering the training itself.

All PhD Aspirants Don’t Want the Same Thing

Let us begin by recognising the persity of reasons for which candidates actually seek a PhD in management (whatever it might say on the programme social science disciplines, but with their own sense of academic identity and no great desire to muddy their hands in the world of practice. The situation has also not been helped by the perception that the social sciences have not been very successful at providing a robust basis for improving policy and practice5.

The doctorate is undoubtedly a research-based degree, but this does not imply that the recipient need only pursue a career in research. Prima facie, there is a market for Educators and Sophisticated Practitioners with PhDs.

The final word on the design of a business school, and by implication of doctoral training in a business school, has therefore by no means been said; this alone is sufficient reason for us in India to avoid an uncritical adoption of existing models of doctoral education. However, an important caveat is worth stating: the most widely successful system for developing reliable and valid knowledge in any field of human endeavour still remains the scientific method − and all its accompanying features, which include a reliance on abstraction, mathematical rigour, the importance of reliable measurement, the validity of causal inference through experimental design, the principle of falsification, peer-reviewed research, etc. No one, not even the proponents of the critiques prospectus, or indeed, in the admission application). While I cannot claim to have data from a systematic survey, my conversations with colleagues and friends engaged in the doctoral education space in India suggest that there are several different segments in the market for doctoral education here.

1. Researcher: Following the award of a degree, the recipient aims to take up a (typically full- time) professional academic career in a university department or business school, in which research and publication in peer-reviewed journals will play the most significant part, though some teaching responsibilities will also exist.

2. Educator: The recipient of this degree will take up a professional academic career in a university department or business school (or in more than one on a part-time basis).The primary activity engaged in is teaching, though the individual may occasionally engage in case writing for pedagogical (rather than research) purposes.

3. Sophisticated Practitioner: In this case, the graduate will (re) enter a career in industry, or occasionally, public policy. The primary activity neither involves teaching nor research, but rather the practice of management itself. In the case of each of these kinds of PhD seekers, the creation of knowledge in some form − whether in terms of peer-reviewed research, pedagogical material or the building of best practice/ policy − features in their post PhD activities; however, there are some other categories of PhD seekers for whom this is less obvious.

4. Job Keeper: As the AICTE mandates begin to take hold, many assistant and associate professors who currently do not have PhDs will be forced to earn them in order to be promoted or retain their positions. While some will see this as an opportunity to enhance their skills as Researchers or Educators, others will simply see this as a ceremonial requirement to be completed in order to keep their jobs.

5. CV Builder: For inpiduals in this categor y, the PhD degree is essentially a vanity product. Apart from enhancing their CVs, the training plays little or no role in the post-PhD life of the recipients.

6. Stipend Seeker: For some candidates, the stipend they receive as a PhD student may be sufficient reward. The degree itself may play no role in the individual’s future, and indeed completion may not be a priority.

I will take it as self-evident that no doctoral programme would see Job Keepers, CV Builders or Stipend Seekers as their ideal candidates for admission. Let us take a closer look at the first category:

The Researcher segment is the one and only segment typically served by B-school doctoral programmes in high status institutions in the US and a few others around the world such as INSEAD and London Business School. A typical programme of this sort is highly selective; often, less than one in 20-25 applicants is selected, and selection continues after admission through hurdles to be cleared in terms of coursework and paper requirements. Exit midway is common and may reach as high as 30-40%. The researchers produced at these institutions go on to compete to publish in the top peer-reviewed academic journals in the field (acceptance rates are typically well below 10% in these journals and impact factors well above 3.0), and if successful, may be awarded “tenure” – a lifetime contract. The job security and the intellectual freedom this provides is supposed to spur efforts in the period leading up to it, and the process of awarding tenure is presumed to screen out those who would desist from research activity post- tenure.

In India, the model of doctoral education we have adopted is one that, at least on paper, focusses exclusively on producing Researchers. It is doubtful though that this has been a very successful move; we can certainly say from the publication data that only a small handful of researchers in management successfully publish their research in the world’s top-ranked journals.

Whether this particular system is the most efficient one to produce high-quality research (or even to indirectly build good teaching and problem solving skills through mere engagement in the research process) is not my main concern here. Instead, I want to point out that even if it works perfectly, the process of doctoral education and postdoctoral life for Researchers consumes a lot of resources and involves significant attrition at various stages. While there is also some scepticism today about the value of most of the research that is successfully published, I do not find that unsettling; this is the hallmark of any search process in a complex problem space. Commercial R&D is no different, with many failures for ever y success.

Thus, I do not doubt for an instant that scientifically valuable and practically useful ideas do emerge from management research. To take just a few examples: consider the impact of research on the practice of asset pricing, market mix modelling, the location of firm boundaries, negotiations, core competencies or brand equity; or the debunking of popular wisdom that occurred through research on M&A performance or art investments. However, we must recognise that the odds of success and the upfront resource commitments are closer in image to the search for blockbuster drugs by pharmaceutical companies, rather than an assembly line producing Maruti cars like clockwork. Perhaps that is as it should be, but that is not the whole story.

Taking PhDs for Non-researchers Seriously

There are many more ways to make a living in the pharmaceutical industry besides engaging in the expensive and risky search for blockbusters. Yet, in the market for doctoral education, the Educator and Sophisticated Practitioner segments are virtually ignored by the top B-schools; in fact, they are actively screened out.

The doctorate is undoubtedly a research-based degree, but this does not imply that the recipient need only pursue a career in research. Prima facie, there is a market for Educators and Sophisticated Practitioners with PhDs. Educators are an important part of the ecology of ever y major business school today − where they often hold titles such as affiliate or adjunct faculty – and play a critical pedagogical role. Business schools the world over are recognising the importance of maintaining a healthy mix of faculty in the Researcher and Educator categories, with appropriate incentives that account for the different kinds of career risks and rewards of each track. I doubt anybody today would really question the value of Educators (or Sophisticated Practitioners who serve as guest lecturers) who have obtained a thorough understanding of the background literature and theory in a domain through a doctoral degree.

Spending meagre resources to try to offer all things to all candidates is a recipe for all-round mediocrity. Putting everyone through a poorly delivered Researcher training programme (even if we throw in the option to do it part-time) and hoping that we end up with reasonable Educators and Practitioners is futile.

The demand for doctoral education by practitioners is latent and yet to be exploited in India. Management PhD programmes in Germany, in contrast, have historically taken the Sophisticated Practitioner segment very seriously, complemented as it is by an ecology in which corporations value Sophisticated Practitioners with PhDs. The Henley DBA is a well-respected doctoral programme in the UK that caters to both Educators and Practitioners, and there are a host of others today in Europe7.

In India, the model of doctoral education we have adopted is one that, at least on paper, focusses exclusively on producing Researchers. It is doubtful though that this has been a very successful move; we can certainly say from the publication data that only a small handful of researchers in management successfully publish their research in the world’s top- ranked journals8. Thus, the over whelming majority of the PhDs in management in India, either by choice or despite it, are not successful Researchers despite very likely having gone through a programme that aims to make them so.

This would be somewhat less worrying if Indian PhD programmes were at least churning out high quality Educators or Sophisticated Practitioners. In fact, if the most useful fruits of research can flow relatively freely across national boundaries (i.e., can be imported), but teaching and practice must be delivered locally, then the case can be made that developing Educators and Sophisticated Practitioners naturally takes priority in India. However, I do not believe this is happening either, because producing Educators and Sophisticated Practitioners also requires at least some specialised inputs, distinct from those that go into creating Researchers. Educators need more training in pedagogy and curriculum design, while Sophisticated Practitioners need more training in diagnostic and consulting skills. With the exception of the IIMs and a few other premier institutions (whose few graduates naturally stay within the system), the skills needed to deliver these kinds of doctoral training are not widespread.

Spending meagre resources to try to offer all things to all candidates is a recipe for all-round mediocrity. Putting everyone through a poorly delivered Researcher training programme (even if we throw in the option to do it part-time) and hoping that we end up with reasonable Educators and Practitioners is futile. We may end up producing Job Keepers, CV Builders and Stipend Seekers, but no outstanding Researchers, Educators or Sophisticated Practitioners9. Paradoxically, the top business schools around the world value enormously the few individuals who turn out be masters at all three – research, education and practice. But their doctoral training does not aim to produce such people, and I think this may be wise − we can revere the outliers like Raghuram Rajan, Nirmalya Kumar or Sumantra Ghoshal, but we cannot yet reliably produce them. My point is that we can improve on the traditional model of doctoral education by producing specialists in each track without necessarily trying to produce triathletes.

Thus, a solution I submit for consideration is to explicitly design multiple tracks for doctoral education. This need not mean that candidates are put in one track or another the day they enter a programme (though that is also possible); rather, similar results could be achieved by letting candidates sort themselves in an informed manner into the track that suits them best.

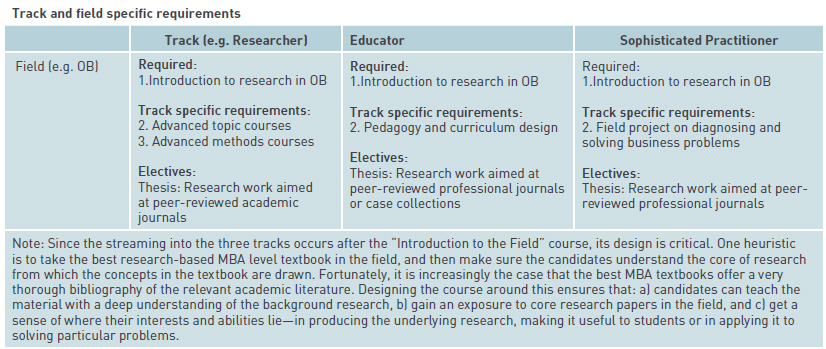

Thus, while a core set of courses would be common across these tracks (see the Appendix for an indicative curriculum), candidates could sort themselves into different streams, perhaps after the “Introduction to the Field” course sequence. Requirements under one track could well be electives under another (e.g. pedagogical case writing could be required for Educators but could be an elective for Researchers). The thesis each type of candidate writes will also be qualitatively different. For instance, a thorough investigation of and creative solution to a single company’s problems should be perfectly acceptable for the award of a degree in the Sophisticated Practitioner track (this is common in engineering schools), whereas a thesis based on a pedagogical innovation, or say a field trial of one, would seem natural for an Educator. Standards for what constitutes the right level of sophistication for these kinds of projects at the doctoral level (rather than, say the Master’s level) will have to be evolved.

There may also be concerns about “brand dilution” and whether it would become necessary to label degrees from the three tracks differently (e.g. PhD vs. DBA vs. an Executive DBA). That is one solution and could avoid confusion particularly in the early stages of a new regime. I suspect though that these concerns are exaggerated; recruiters will very likely develop the competence to be able to understand which “track” a candidate is from, whatever it says on the degree.

Of course, not ever y institution needs to cater to all three tracks; there may well be gains from specialisation. The ability to pay for the degree as well as the cost of providing training also varies widely across these segments. One could conceive of stand- alone doctoral programmes that primarily train just Sophisticated Practitioners or Educators. However, the economies of scope and possibilities for cross- subsidisation I have noted above suggest that this choice of “product mix” needs to be carefully thought through. For business schools who take their research mission seriously, having a programme that trains Researchers is a must, but they could additionally consider programmes that train Sophisticated Practitioners (which may bring in additional revenue) and Educators (thus filling an urgent need in the ecosystem). Perhaps the biggest gains will come from the ability to invest scarce resources − scholarships, faculty time and research budgets − in a more discriminating manner.

Conclusion

One fact seems inescapable: the next few years will see a dramatic explosion in the scale and importance of doctoral education in India, given the mismatch between demand and supply. To meet this demand, we can keep doing what we are doing, which is basically trying to replicate a particular model of doctoral education (which also happens to be the most resource hungry one) with insufficient resources to support it; we will print many degrees but I am not sure we will educate many doctorates. Or we can be innovative and tr y to use the opportunity to build better models from scratch − ones that work for us and are free of the legacy constraints of models from around the world. We could do for doctoral education in management what the Indian mobile telephony companies have done for the global telecommunications sector.

I have proposed one blueprint, which involves recognising the broader possibilities of doctoral education in management. Surely there are other possible blueprints. Let the conversation begin.

Acknowledgements:

I have had the benefit of discussing the ideas in this paper with several colleagues on several occasions: Professors Jay Mitra (FMS), Massimo Warglien (Venice), Markus Reitzig (Vienna), Nirmalya Kumar (LBS), Madan Pillutla (LBS), Ravee Chittoor (ISB), Sanjay Kallapur (ISB), Chirantan Chatterjee (IIM-B), Bala Vissa (INSEAD), Jasjit Singh (INSEAD), Quy Huy (INSEAD) and most recently with the doctoral educators who participated in a workshop on “Building the Foundations of Management Research in India,” organised by AIMA. Dr Ganesh Singh (AIMA) and Research Associate Deepak Jena (ISB) provided the statistics quoted on the first page. My thanks to all of them. All errors (and inflammator y opinions) are my own.

Appendix: An Indicative Curriculum for a Multi-track Doctoral Programme in Management

Minimum general requirements common to all fields and tracks

1. Basics of scientific method and philosophy of science: Essentials of hypothesis formulation; theor y as explanation; mechanisms; the principle of falsification; the nature of progress in the sciences; business school research as applied social science.

2. Understanding Organisations: Basics of organisational behaviour; inpidual motivation and cognition; decision making and learning; groups; the nature of authority; hierarchies; organisation structures; culture and networks; the organisation designer’s perspective.

3. Understanding Markets: Basics of micro- economics; rational choice; demand and supply; perfect competition; monopoly; duopoly and oligopoly; introduction to game theor y; the policy maker’s perspective.

4. Quantitative methods: Basic statistics; t-tests; ANOVA and ANCOVA; Ordinar y least squares regression; factor analysis.

5. Qualitative methods: Basics of qualitative methods; case-based research strategies; induction from cases; categor y construction; inter viewing skills; linguistic text analysis; Boolean qualitative comparative analysis of cases.

NOTES

1 I will use “management” to refer broadly to all the fields taught in a business school. Since my familiarity is greater with some fields than others, I ask pardon in advance from colleagues who might find my arguments to be either irrelevant, or worse, incorrect about their particular fields.

2 Data sources include: http://www.aicte-india.org/ misappmanagement.htm, accessed October 22, 2012; AICTE Handbook 2013-2014; UGC annual reports (2005-06 to 2010-11); Higher Education in India at a Glance, UGC 2012; Hindu Business Line article (http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/features/ newmanager/article3505650.ece).

3 See for instance Simon, H. A. “The Business School: A Problem in Organizational Design,” Journal of Management Studies 1967

4 For an indicative, but by no means isolated example, see Khurana, R., and J. C. Spender. “Herbert A. Simon on What Ails Business Schools: More than a Problem in Organizational Design,” Journal of Management Studies (2011).

5 See for instance the critiques of Tooby J., and L. Cosmides.“Better than Rational: Evolutionary Psychology and the Invisible Hand.” American Economic Review (1994); E.O. Wilson. Consilience: the Unity of Knowledge. New York: Knopf, 1998 and Giggerenzer, G. Bounded Rationality: the Adaptive Toolbox. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

6 It is also worth bearing in mind that most of the fields of research that exist in a business school are at most decades old; for their youth relative to the older social sciences, I would argue that some fields like finance, operations research and marketing are already giving a good account of themselves.

7 The Harvard DBA was not explicitly designed to focus on producing practitioners or educators per se, to the best of my knowledge.

8 See the analysis in Chapter 6 of India Inside by Nirmalya Kumar and Phanish Puranam, HBS Press, 2012; the gist is summarised in: http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/opinion/ view-point/taking-stock-of-indian-management-research/ articleshow/7440640.cms

9 The counterexample of the natural sciences may come to mind, where the same PhD programme apparently trains both academic researchers and those who work in the corporate world, but this is misleading because the academic researcher must also undergo extensive postdoctoral training while the corporate researcher need not.