The quest to be recognised as a global leader in innovation led Biocon to discover and develop IN-105, oral insulin for diabetics. Faced with initial success, the Biocon team was rearing to charge ahead with the final testing. Everything looked rosy, but was it actually so? Nita Sachan, Senior Researcher, Biocon Cell for Innovation Management at the Centre for Leadership, Innovation and Change (CLIC), Prasad Kaipa, Senior Research Fellow & Director Emeritus, CLIC, Anand Nandkumar, Assistant Professor of Strategy, ISB and Charles Dhanaraj, Head & Senior Research Fellow, CLIC are co-authors of this case.

“It has been my dream to make a global impact with a “Made in India” label. I think a lot of my generation comes from that frame of reference. We have always had to apologise for India and now is the time we don’t want to apologise for our country. We want to be proud of it.” – Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw

The morning of April 27, 2009 witnessed intense activity at Biocon’s Bangalore office, where the future of oral insulin IN-1051 was being discussed. As they completed their presentations to the committee, Harish Iyer, Head of R&D at Biocon, and Anand Khedkar, Senior Scientific Manager of the project, posed a tough question before Biocon’s senior management: How much risk was it ready to take with IN-105?

Biocon’s management was faced with the dichotomous situation of a financial crunch due to declining profit margins in 2008-09 on the one hand, and the possibility of creating a global profile as a leading Indian innovator, on the other. Encouraged by positive global reviews from Phase II studies of the IN-105 concept, management at Biocon was toying with the idea of proceeding with Phase III studies. Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, Founder and CEO of Biocon, was in a dilemma with regards to the scale of the study – whether to have it within India or outside; should it be done in-house or with a partner? Unlike many of Biocon’s projects in the generics arena, this project would require a significant resource commitment, with very little guarantee of success. However, if successful, it would open up a substantial global opportunity for the company.

Biopharmaceuticals Industry

The global biopharmaceuticals industry revenue was expected to grow at compound annual growth rate (CAGR) 3.6% from 2008 to reach US$ 734 billion by 2013. The biotech sector alone had been growing at 10.2% per annum from 2005 to 2009 and was expected to reach a value of US$ 318.4 billion by the end of 2014. The biotechnology industry was mainly located in advanced global economies. India ranked 11th world over with 325 firms and was ranked 4th in Asia-Pacific.

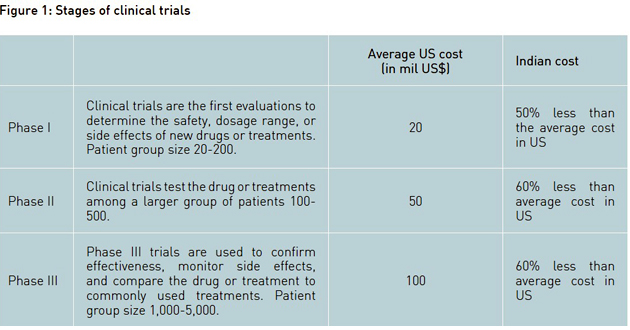

The industry developed products through discovery R&D (production of new chemical entities or NCEs) as well as reproduction of generics (drugs which were in the market, but out of any patent protection). A company got patent for a new chemical entity (NCE) or a production process for only 20 years, after which generic drug versions could be developed and sold by other companies. Drug development, from discovery to marketing, was estimated to require an investment of nearly US$ 1 billion and industry profitability was under constant attack as costs continued to rise and prices came under pressure. Industry experts estimated that on an average only 25 truly novel drugs, termed within the industry as NCEs got approval for marketing in any single year. This approval involved a heavy investment in pre-clinical development and clinical trials, as well as a commitment to ongoing safety monitoring. What added to the woes was that the development of any NCE took 10 to 15 years, going through three main phases of clinical trial (see Figure 1). Thus, having only 20 years of patent protection meant that companies hardly had time to recover the money they had invested. Adding fuel to fire was the fact that development and approval of generics was less risky and inexpensive compared to the original drug. Generics were typically sold at one-tenth of the original drug price, if not less.

As drug development costs soared, global pharma companies started looking to emerging markets such as India and China, where pharmaceutical production and clinical trial costs were at least 50% lower than in Western nations. Although funding continued to be a major constraint, several Indian firms got encouraged by the new patent regime coupled with the large pool of local talent and returning Indian diaspora, to foray into discovery R&D and the generics business. Mazumdar-Shaw reflected:

“The Indian pharmaceutical sector in general has thrived on generics or me-too products. In the biotech industry, too, most companies are opting for bio-generics. In Biocon, we have balanced our portfolio between bio-generics and novel research programmes. The talent you require for bio-generics is no way inferior to novel research. Yes, you have to invest far more because you’re doing something for the first time. The difference between bio-generics and novel research isn’t so much about the talent as the management’s risk appetite.”

Biocon Over the Years

What started as a small biotech garage-outfit in 1979, in less than 30 years became the number one biotech firm in India with global sales of US$ 712 million in more than 75 countries. Biocon’s product portfolio consisted of 36 key brands across four therapeutic divisions of diabetics, nephrology, oncology, and cardiology. Mazumdar-Shaw led the company through several international partnerships and joint ventures. She ensured that the company remained up to speed with market developments and steered Biocon and its subsidiaries3 into different areas of the biopharmaceuticals business. While the company had shied away from overly aggressive moves, it had consistently moved ahead in its quest to establish itself as an innovation leader. Keeping with this spirit, in 2003, she decided to move Biocon’s focus from the flourishing generics business to discovering NCEs. One such NCE was IN-105. Mazumdar-Shaw recalled:

“We believed that we had some advantage to focus on the oral insulin research programme. For a programme like this, the cost of goods is a major factor to be able to make commercial success. Our location, India, was a huge advantage for us in this. We can actually bring commercially viable oral insulin into the world market. Oral insulin would have a unique therapeutic effect as compared to plain insulin because of the way it is delivered. I really believe that it has the potential of reversing early stage diabetes.”

In the past several companies had made failed attempts at oral insulin formulations. Undeterred by this fact, Biocon continued developing IN-105 and had successfully completed Phase II of the clinical trial. Globally Biocon’s IN-105 was considered one of the oral insulin programmes furthest along in its development. Many within Biocon felt that whether to go to Phase III or not was not the question. Since they had successful Phase II studies, the logical next step was to continue on with Phase III. But the exact way to go about it was what required deliberation.

As the management committee was meeting to finalise its strategy for IN-105, three major issues specific to IN-105 would be raised at the meeting: Should Biocon undertake this risky investment now? Should the clinical trial be local or global? And should they go with or without a partner? There were several issues which were brought to the fore: Phase III trials required huge investments and Biocon was just recovering from a major financial crunch after the global recession of 2008; several major pharma companies in India were shutting down their R&D units; moving to Phase III in India had its own advantages and risks, and the net value that a global partner would add was not known clearly.

Overall, there was consensus that IN-105 had the potential. However, the challenges associated with the molecule were not trivial. Along with the execution strategy, senior management also pondered over Biocon’s ability to manufacture it at a lower cost in order to market it at a sellable price. Iyer and Khedkar were convinced of the move forward. Khedkar remarked:

“For over a hundred years, no one has been able to change the way insulin is administered. If Biocon is able to do it, then it completely changes the way diabetes is treated. Even if we fail, each step is a learning process for Biocon’s long term R&D capabilities.“

Mazumdar-Shaw clearly indicated the management’s intentions with her opening statement at the meeting:

“It is prudent at a time like this to remain committed to our innovation-led business strategy, which we believe will enable us to build a strong competitive edge for the foreseeable future. Innovation, we firmly believe, holds the key to leadership and profitability.”

The case summary was written by Arohini Narain, Centre for Teaching, Learning and Case Development (CTLC) at the ISB.