In 2015-16 India suffered one of the worst and most widespread droughts in decades, which affected nearly half of the country’s districts. The average rainfall fell by 14% below normal during monsoon and by 23% in the post monsoon period (IMD 2015). Across India some of the major water reservoirs in rain-deficit states were holding only 21% of their normal capacity (Central Water Commission 2015). The severity and impact of the drought was felt most strongly by resource-poor farmers whose livelihoods and food security was affected. While the attention of the government, media and public at large has been focused on debt-ridden communities and rampant farmer suicides, households whose agricultural livelihoods are tied to the weather and the availability of water have certain coping mechanisms to prepare for unpredictable weather. Millions of households across rural India plan and strategise to mitigate the impacts of drought.

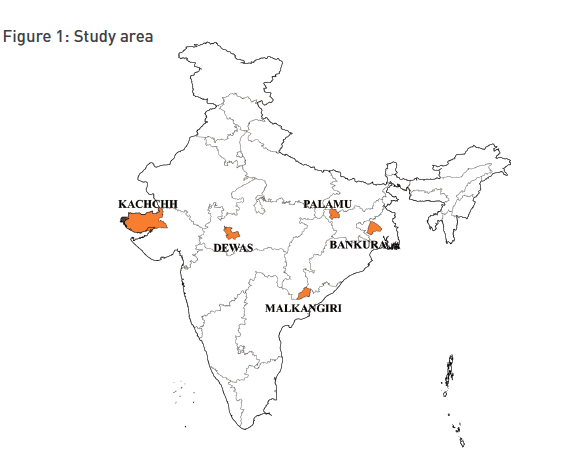

In our study, conducted in five states across India during May-June 2016, we aimed to study these different responses and strategies. The research was conducted and supported by the RRAN (Revitalising Rainfed Agriculture Network). Across our fi ve study sites, we were supported by partner organisations namely Arid Communities and Technologies (ACT) in Kachchh (Gujarat), Samaj Pragati Sahyog (SPS) in Dewas (Madhya Pradesh),Vikas Sahyog Kendra (VSK) in Palamu (Jharkhand), Parivarttan in Malkangiri (Odisha), and Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN) in Bankura (West Bengal).

The study villages were selected on the basis of four criteria: a) villages with high proportion of marginalised social groups, such as scheduled castes (SC) and scheduled tribes (ST), b) Distance from road, c) Distance from block headquarters, and finally d) Number of common and private surface water sources. Within the study villages 780 households were selected across all five sites using random sampling. We only sampled households owning land so that we could study the strategies undertaken following crop loss. Of the total households in our sample 63.7% are ST, 5.8% are SC, 21.4% are OBC and 9.1% fall under general category households.

A survey of five drought prone states across India by ISB researchers shows that even as farming households wait for elusive government support they devise their own coping mechanisms to address the fallout of drought. Having said that, the findings of the study point to the urgency for decision makers to prioritise drought mitigation and adaptation strategies and for better targeting of investments in rain-fed agriculture.

Household-level Responses to Drought: General Trends

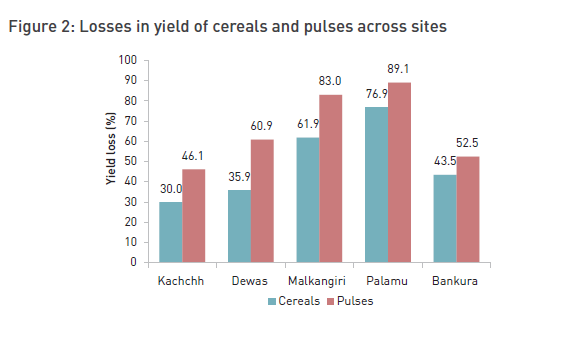

Across all five states we found extensive losses in the yield of cereals and pulses. Looking closer (Figure 2) we can see that all five sites were badly hit. Palamu district in Jharkhand reported the highest loss for both pulses (89%) and cereals (76.9%). Overall, there was a huge gap between expected yield and the actual yield during drought.

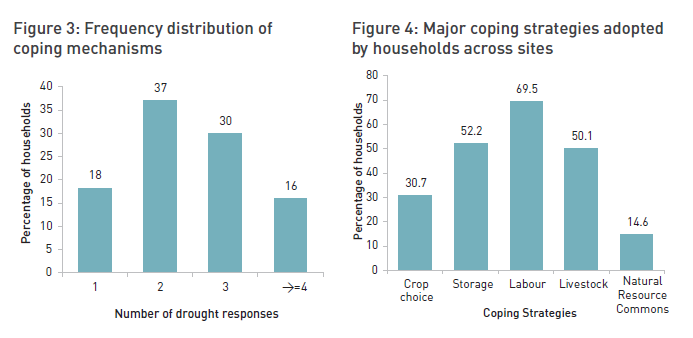

While the impact of drought has been severe, its effects have been felt differently across different geographies. Most households adopted more than one strategy or coping mechanism to tackle the drought situation. Out of all sampled households 83% adopted at least two strategies, and 46% adopted three or more strategies to mitigate the loss of income due to drought (Figure 3).

We recorded nearly 2000 responses at the household level in our sample, and identifi ed five distinctive patterns and similarities in the coping mechanisms adopted by households across all five states (Figure 3). These are:

1. Crop choice

2. Food storage

3. Livestock

4. Wage labour

5. Natural Resource Commons

While the attention of the government, media and public at large has been focused on debt-ridden communities and rampant farmer suicides, households whose agricultural livelihoods are tied to the weather and the availability of water have certain coping mechanisms to prepare for unpredictable weather.

Crop Choices

Across our five sample sites, 30.7% of households changed their choice of crop as a response to successive droughts (Figure 4). These include widespread shifts from cash to food crops. Farmers are also changing the nature and quality of seeds, scaling up area under specific crops and growing crops which provide multiple benefits such as food, fodder, and income.

Shift from cash crops to food crops

One of the major responses to drought was a clear shift in crop choices. Farmers who were mostly dependent on cash crop for a steady fl ow of income earlier have now increasingly shown a shift towards food crop. These households have either increased the area for food crops while decreasing area under cash crops or started growing food crops which they were not growing previously. Food crop grown is mostly used for self-consumption and some portion is stored to be sold later in times of need.

In Dewas, farmers have reduced the area of soya and cotton and have increased the area for food crops like maize, tuar, chawla and other pulses. In Kachchh, farmers who were earlier growing groundnuts have now shifted to crops like sovin and jowar.

Shift towards high yielding variety (HYV), traditional and hybrid seeds: We found some sites where the crop pattern remained the same but the choice of seeds, quality etc. have changed gradually. This happened because farmers in these areas have realised that good quality seeds could save their crop to some extent during drought. Access to these HYV seeds has also become much easier now, because it’s available in local markets. The Agriculture Department and local NGOs have also played a crucial role in providing subsidies and other information related to these varieties.

In both Malkangiri and Bankura, farmers have shifted to using seeds for short duration varieties, which take less time to harvest in comparison to the previous varieties. In some cases a move to traditional varieties, preferred for their low water requirement was also recorded. Across all sites, however, farmers are shifting to hybrid varieties, primarily for higher yields.

Crop choices and linkages to fodder supply

Farmers are choosing crops that can also supply significant fodder resources. This is because during dry spells and drought years generally there is a significant decline in fodder availability. Also, market supply of fodder is expensive and often unaffordable; so farmers strategically planned to cultivate crops which could serve the purpose of both food and fodder.

Farmers in places like Kachchh, which are major livestock economies, have managed to take care of their major fodder supply needs through cultivating crops like sovin and jowar, primarily for their fodder value. Similarly in Dewas, maize and wheat are grown to provide fodder, in addition to food and cash income. In Malkangiri, Bankura, and Palamu, paddy is targeted to produce both food grains as well as fodder.

Food Storage

Across our five sample sites 52.2% of households increased the storage of food grains as a response to drought (Figure 4). Food storage is one of the most prominent strategies adopted by households in our sample across all five states. The primary objective behind storing food grains and pulses is self-consumption, though the marketable surplus used to be sold for cash income. However, after the widespread crop failure in the last two years, farmers who would otherwise sell most of the produce are choosing to store most of it.

In Bankura, all the paddy was stored this year. In Malkangiri, farmers have been in the habit of storing enough food grains especially Ragi, that will last them for two crop cycles. Similar trends could be seen in Palamu, Kachchh and Dewas as well, where farmers have scaled up their storing practices and storage capacity to avoid hunger and stress during drought.

Across all fi ve states we found extensive loss in the yield of cereals and pulses. Looking closer (Figure 2) we can see that all fi ve sites were badly hit. Palamu district in Jharkhand reported the highest loss for both pulses (89%) and cereals (76.9%). Overall, there was a huge gap between expected yield and the actual yield during drought.

Livestock

Across our five sample sites 50.1% of households increased livestock as a response to drought (Figure 4). Livestock is a very important aspect of rural livelihoods. During drought conditions, livestock is of utmost importance for a household’s income. From own consumption to selling livestock for various purposes, livestock helps sustain a rural household in multiple ways. The cash obtained from selling livestock helped in buying essential goods and repaying credit by the households. In the aggregate and on average across the sampled households, there was an increase in the herd size of various livestock.

Increase in the size of small ruminants and other livestock (stocking): In Bankura, Malkangiri, and Palamu, majority of households have been investing in increasing the stock of small ruminants (goats) and others (poultry) and selling them for better cash flow. Earlier they did not keep livestock (small ruminants and others) in such large numbers.

One of the major responses to drought was a clear shift in crop choices. Farmers, who were mostly dependent on cash crop for a steady flow of income earlier, have now increasingly shown a shift towards food crop. These households have either increased the area for food crops while decreasing area under cash crops or started growing food crops which they were not growing previously.

There has not been any significant change in the number of large ruminants like buffaloes and cattle. They are essentially kept for draught power or dairy production, but in small numbers. Goats and poultry are easy to maintain, and investment in their food and maintenance is relatively low. Across the fi ve sites there has been no additional investment to purchase small ruminants and other livestock. These are bred within these households to increase herd size.

In Dewas, there is a shift from large to small ruminants and other livestock (poultry). Buffaloes and cows are sold to purchase goats and hens as they are comparatively easier to maintain. Only in Kachchh do we notice an increase in the number of cows and buffaloes. Investments in Banni buffalo for dairy production have been taking place to a great extent. For the last two years and in response to drought, dairy production in these households has become the major source of income in order to compensate for crop losses.

Wage Labour

Across our fi ve sample sites, 69.5% of households increased duration of wage labour as a response to drought (fi gure 4). This is seen across skilled, unskilled or agricultural labour. Labour work is done on a seasonal basis, and whenever work is available. When farmers face large-scale crop failure, debt and limited cash fl ow labour work not only becomes important but necessary. It helps families to get cash fl ow without much delay. They often use this income to buy essential goods for their households, putting their children through school, or for paying off their debts. Using their social networks they get information about the availability of work in neighbouring villages, towns, or even faraway cities.

We can see two broad patterns emerging with respect to wage labour as a response to mitigate the impact of drought:

1. Increased number of work days: Families have been increasing the duration of days they spend doing wage labour work. In Bankura, villagers go to the neighbouring district of Bardhaman for agricultural labour for up to three months rather than for a month as they usually did. In Palamu, women migrate for agricultural labour to Bhojpur in Bihar. While this migration has been happening for quite some time now, we notice that the duration of migration has increased. Not only have the days of work increased for many families but often more members of these households are now involved in wage labour. In some cases women who never migrated or did wage labour work earlier are now travelling outside the village as well.

2. Increasing the distance travelled: People are also travelling farther for wage work. In Bankura, many of the villagers used to migrate to near by Purulia town for work. However, in the last couple of years, the number of labourers have increased and saturated these traditional destinations, prompting other labourers to travel further. In Palamu one can see a defi nite shift with villagers travelling to faraway cities in search of work. In Malkangiri and Kachchh there is less migration, but labourers travel further locally in search of labour.

Natural Resource Commons

Across our fi ve sample sites, 14.6% of households increased their access to natural resource commons (forests, grasslands, reservoirs, etc.) as a response to drought (Figure 4). Commons are of utmost importance in a rural landscape. They act as buffer zones in that they often provide supplementary resources, which can be utilised by the households in times of need. These commons provide households with opportunities for both sustenance and income. Goods accessed from the commons are traditionally sold for additional income. However, in the recent drought this has become one of the main sources of income for at least some households.

We can see two major patterns

Increased access of commons for income and sustenance: In Malkangiri, Palamu and Dewas, many households go to distant areas and forests for collecting firewood, tendu leaves and mahua flowers. In Malkangiri households collect wild food (like mushrooms, berries etc) sporadically, for sustenance. In Bankura and Malkangiri fishing activities have increased, and now families go for fishing at least 4-5 times a week. In Kachchh certain communities make charcoal from the Babool tree, which grows on common lands. This has been a regular practice for many years but has recently intensified as a response to drought.

Increased access of grazing lands: Grazing lands are being used more than before. As households are increasing small ruminants, the demand for grazing lands is increasing proportionately. Quite a few households have also reported increased mobility as they travel farther to access other forests or pastures, for grazing.

Discussion

Farmers are adopting multiple strategies to cope during adverse situations. Households adopt certain practices to reduce their risk and vulnerability. Markets and other institutions like government departments, civic institutions and social protection programmes play a crucial role in providing support and assistance. It is also significant to note that these responses have had an impact on women’s workload. These are discussed below:

Markets: Market acts as a safety net by providing immense scope for households to sustain their livelihoods. It provides a platform for exchanging, buying or selling goods that would otherwise be difficult to access. It also acts as a centre for exchange of ideas and information. It helped in mitigating crop losses to a great extent by opening avenues for income generation and sustenance. It played a significant role in supporting the coping mechanisms adopted by households during drought with respect to crop choice, food storage, wage labour, livestock and commons.

Farmers in places like Kachchh, which are major livestock economies, have managed to take care of their major fodder supply needs through cultivating crops like sovin and jowar, primarily for their fodder value.

For instance, due to availability of HYV seeds and less water-intensive technologies like drip irrigation in the market, farmers have been able to respond to the drought through changing crop choices. Households were able to access information about migratory or local wage labour opportunities through a network of agents and contractors. Products, collected from commons, like tendu leaves or firewood etc. were sold by the households in the market for cash income. Markets helped in providing different types of goods and services for storing food grains, fodder, water etc.

Social Protection: Social safety nets play a crucial role in alleviating poverty and reducing risk and vulnerability. Two of the largest social protection programmes in India are the NREGA (National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) and PDS (Public Distribution System). Under NREGA people can apply for work when they most need it. However, in the drought-hit districts that we studied, respondents reported that NREGA had not served its role as a safety net. Households in Malkangiri worked for an average of 30 labour days under NREGA, but in all other sites it is practically nonexistent. In contrast, the PDS system performed extremely well in providing subsidised food. From January-April 2016, all households received their food entitlements to a very high degree across all states, with Palamu falling slightly short of full coverage.

A renewed policy focus, better targeting of resources, and increased investment to improve the working of local drought mitigating mechanisms is needed. Increased policy support and investment to improve working of labour, credit, and water markets will strengthen household resource productivity and drought coping mechanisms.

Social protection programmes are especially important during drought. Since households require immediate cash fl ow in times of need, widely reported delays of payments may have led to poor performance of NREGA. On the other hand, there is evidence to suggest that the PDS has had a revival in the last several years in many parts of India (Khera, 2011). Hence, even though one of the sites (Palamu) reported irregular food supply, this social protection programme has clearly proven useful. Public policy has to be geared towards improving and strengthening social protection programmes, so that it is able to support households and help in mitigating the effects of adverse shocks.

Gender Dimensions: The drought responses discussed earlier have led to a significant increase in womens’ work load, but this is usually overlooked. Women do not often have the space to negotiate about their share of the workload. For example, if a household is increasing its livestock size then it’s the responsibility of the women and children of that household to take care of its fodder and water requirements. Similarly, when tendu leaves, firewood and other resources from commons are increasingly accessed, women and children are responsible for that extra effort. Drought, as well as the household responses to mitigate the impact of drought, have put these families in a vulnerable position and increased the responsibilities and share of womens’ workload.

Conclusion

This study examined the household responses and coping mechanisms to drought across selected states of India during 2015-16. These findings are important for stakeholders and decision makers as a reminder to prioritise drought mitigation and adaptation strategies, and better target efforts and investments in rain fed agriculture.

A renewed policy focus, better targeting of resources, and increased investment to improve the working of local drought mitigating mechanisms is needed. Increased policy support and investment to improve working of labour, credit, and water markets will strengthen household resource productivity and drought coping mechanisms. Provisions need to be made for improving local food and feed storage capacities at village and community levels, livestock care and health facilities, and institutional mechanisms for better productivity. Finally, there needs to be a focus on the sustainable management of common pool resources as a priority area of policy support and investment.

REFERENCES

Annual Climate Summary 2015. Pune: India Meteorological Department, 2015. Print.

“Central Water Commission – An Apex Organization in Water Resources Development InIndia”. Cwc.nic.in. N.p., 2016. Web. 22 July 2016.

Khera, Reetika. “PDS- Signs Of Revival”. THE HINDU 2011.Web. 22 July 2016