Developing countries are increasingly vulnerable to climate change related risks due to their geographic, socio-economic, and environmental endowments. In the recent past climate change has triggered more frequent and intense weather events (e.g. droughts, fl oods, heat waves), affected global water resources and food supply, increased the spread of infectious diseases, caused loss of biodiversity and has increased rural-urban human migration (IPCC 2013). There exists a general consensus now at the national and international platforms for the need to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to avoid climate related disasters, which can otherwise cause large-scale human and ecological destructions. At the international level the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the primary mechanism which coordinates the international efforts for implementing the climate change actions.

Studies show that the developing countries are more likely to be vulnerable to the impacts of climate variability, as population in these nations are particularly reliant on ecosystem services and climate sensitive sectors such as agriculture, forestry, etc. (see World Bank 2010). Further, the already degraded natural resource base, coupled with high levels of poverty and population density, will make developing countries more vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Finally and most importantly, developing countries have limited financial and institutional capacity to adapt to the effects of climate variability (IPCC 2013). Implementing mitigation and adaptation measures in the developing world is, therefore, crucial, where climate change is becoming an issue of significance, both environmentally and politically.

Socio-economic development is the main driver of anthropogenic climate change. Quite arguably, climate change is then directly related to the core elements of human society which broadly includes infrastructure systems (energy, industry, and technology); forms of social and economic organisation, life-styles, and values; and institutions and governance (Marhofer and Gupta 2015). Institutional aspect is a prominent concern particularly in climate change mitigation as the impacts of climate change are generally long term and multidimensional, encompassing many sectors (e.g. agriculture, finance, water etc). Further, understanding the institutions and their capacities is crucial for deciding the next steps of climate actions that are most appropriate under national circumstances.

India, with its projected increase in population and economic growth as well as its high reliance on agriculture, is anticipated to be facing greater risks due to climate change. In response to addressing the climate change problem, India has developed a co-benefit approach – the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) – in 2008. However, the need for addressing institutional aspects for effective implementation of climate measures in India is well argued (Dubash and Joseph 2016). Based on secondary research the present review examines current institutional arrangements for implementing climate change actions in India. It further provides a synthesis of perspectives from various primary and secondary source programmes, about the institutional gaps in the current framework to support the co-benefit approach of climate change mitigation in India..

A right mix of top-down and bottom-up approach is needed for meaningful outcomes from a climate policy. To this end, the strengthening of institutional aspects are crucial in facilitating and engaging players and institutions at all levels to effectively implement both national and state level climate action plans.

The National Action Plan on Climate Change – Current institutional arrangements

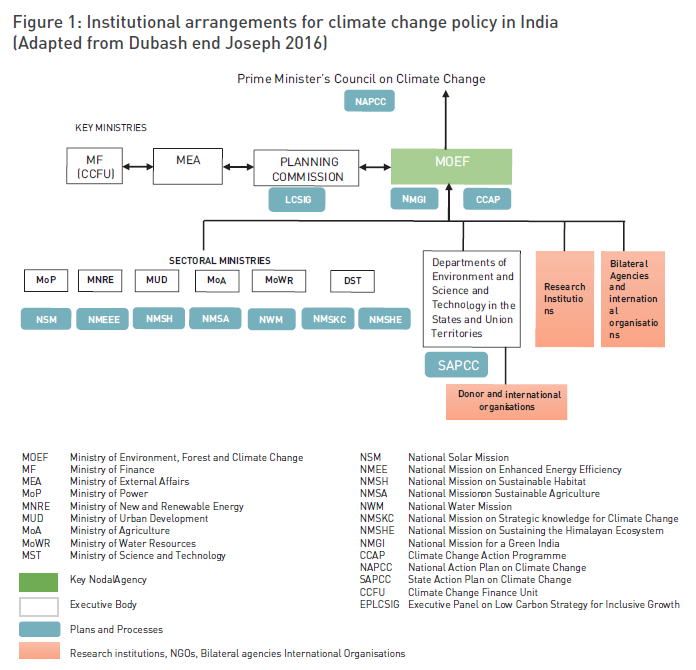

A growing concern about the increasing vulnerability of India to climate change impacts and the issues concerning energy insecurity resulted in the development of the NAPCC. NAPCC adopted by the Indian Government in 2008 recognises measures ‘that promote India’s development objectives while also yielding co-benefits for addressing climate change effectively’ (GOI 2008). It proposes actions that need to be implemented in the country to address climate change as well as it provides updates of India’s national programmes relevant to climate change. The NAPCC consists of eight national priority measures representing long term integrated strategies, achieving the goals of adaptation, mitigation, energy efficiency and natural resource conservation. Following NAPCC major institutional changes took place in the Indian climate policy to support the new co-benefit approach. The Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEF) is the lead agency that plans, promotes, coordinates environmental and climate change policies and programmes in India. It also serves as the nodal agency for international cooperation in the area of climate change. The institutional arrangements for climate policy in India are graphically depicted in Figure 1.

It is increasingly recognised that the climate change is an economic problem and is closely linked to developmental challenges. Following the development of a co-benefits based climate action plan, the Indian policy-making process primarily involved Ministry of Finance (MoF), Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) and Planning Commission to work closely with the MoEF in order to incorporate fi nance, development and environmental agendas into an effective climate policy. An Expert Group on Low Carbon Strategy for Inclusive Growth (LCEG) was jointly formed by Planning Commission and MoEF for the establishment of a pathway for low carbon development to bring technical input into larger developmental framework. Thus the 12th National Five Year Plan included some major mitigation and adaptation strategies in the national developmental objectives. Similarly, a Climate Change Finance Unit (CCFU) is formed under MoF to facilitate and direct the international climate fi nance (Figure 1).

Developing countries are more likely to be vulnerable to the impacts of climate variability, as population in these nations are particularly reliant on ecosystem services and climate sensitive sectors such as agriculture, forestry, etc.

Further, the sector ministries, namely, Ministry of Power (MoP), Ministry of Urban Development (MUD), Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), Ministry of Water Resources (MWR), Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) and Department of Science and Technology (DST), are designated as the key nodal ministries for the delivery of each of the eight national mission under the guidance from MoEF and the NAPCC (see Figure 1). Each of these sector ministries are responsible for providing documents stating the objectives, implementing strategies, timelines, monitoring and evaluation criteria to the Prime Ministers Council on Climate Change (PMCCC) for the final approval and funding (Jha 2014).

Environment ministries and departments of Science and Technology at the state level and Union territories deal with the state specific climate change action plans through the guidance from MoEF. Also, research institutions and bilateral agencies and international organisations support MoEF in their respective capacity for the overall implementation of NAPCC.

During 2011 several states made an effort to develop State Action Plans on Climate Change (SAPCC), with support from MoEF. Although Centre directs the development of SAPCCs, the content of SAPCCs is shaped by the priorities of each state in terms of their long term developmental agenda, as well as specific climate vulnerabilities and opportunities such as resource availability (Atteridge et al. 2012). State departments are also in direct coordination with international bilateral and multilateral donor organisations for implementing climate change actions in their respective states. Many internationally funded projects now interface directly with state governments. Scientific and technical staff and an army of experts support administrations at the Union and state levels in developing and implementing climate change plans.

Institutional inadequacies in the current framework

As detailed in the previous section, following the announcement of NAPCC, institutional arrangements for climate change in India witnessed some changes, including restructuring of executive bodies and establishment of new climate institutional units within nodal Ministries (e.g. CCFU and LCSI in MoF and PC) to fulfill the agenda of eight national missions. However, these modifications in the institutional arrangements are not well matched with the influx of the ambitious climate agenda. Also, policy and practice remained largely unchanged and institutional gaps continue to exist as before (Mayrhoferand Gupta 2015 and Dubash and Joseph 2016). The following section describes these institutional gaps, that are present in the current institutional framework, to support the new climate agenda, and presents arguments on how each of these institutional aspects is critical to effectively implement national climate missions.

India with its projected increase in population and economic growth as well as its high reliance on agriculture is anticipated to be facing greater risks due to climate change. In response to addressing the climate change problem, India has developed a co-benefit approach & the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) & in 2008.

Coordination mechanisms

Coordination ensures that the departments and organisations, both public and private, that are responsible to deliver the climate policy and mitigation actions, work closely together and avoid duplication of each other’s work or allow gaps in services (Nakhooda and Jha2014). For the implementation of NAPCCs missions, coordination is particularly important between ministries and their programmes (i.e. horizontal), as well as to connect central agencies with state and local institutions (i.e. Vertical) and non-state actors.

Establishment of key coordination mechanisms is vital for the smooth processing and implementation of national missions. There are insufficient formal coordination mechanisms in the climate institutional context of India, and in that coordination primarily occurs in an ad hoc manner either through special committees in the case of missions or through bilateral consultations between MEA and MoEF (Dubash and Joseph 2016). In the past the office of the special envoy performed this task of coordination, which helped to bring about substantial progress during the initial stages of development of NAPCCs. However, after the dismantling of the office no institution has been formally assigned the responsibility of coordinating across ministries and executive bodies. In the present Indian institutional context an institution performing the task of coordination appears to be important. Such an institution with sole responsibility of coordination will not only help ease communication and cooperation among mitigation programmes but will also emphasise the accountability of the actors for effective implementation.

On the other hand, vertical coordination is virtually missing due to the strong central (federal) focused institutional nature of climate policy making in India. The inherent nature of the cobenefits approach cuts through various sectors and programmes that are shared or subject to individual state’s policy. This results in a rigid situation where the centrally directed approach needs customisation of specific elements of policy to the local context (Mayrhofer and Gupta2015). This situation can only be resolved through appropriate vertical institutional coordination which is currently lacking in Indian climate policy.

During 2011 several states made an effort to develop State Action Plans on Climate Change (SAPCC), with support from MoEF. Although Centre directs the development of SAPCCs, the content of SAPCCs is shaped by the priorities of each state in terms of their long term developmental agenda, as well as specific climate vulnerabilities and opportunities such as resource availability (Atteridge et al. 2012).

Stakeholder involvement

Because the co-benefit approach is an umbrella concept and its programmes encompass areas of development, agriculture, energy, climate etc, its implementation requires active participation of actors from all sectors for a meaningful outcome. The arguments presented in the literature confirm the participation of specific actors group is largely limited in the current climate governance of India. Research suggests that very few opportunities were provided for public input and other consultations in the processes of both policy making and institutional development (Dubash and Joseph 2016). It is further emphasised that inadequate stakeholder participation is evident in all steps of the climate policy making in India. To mention a few – development of NAPCC was largely a closed process, establishment of LCSIG and some national missions had minimal or no consultations; and SAPCCs are mostly government driven processes (Dubash and Joseph 2016). These are some of the instances that demonstrate limited involvement of stakeholders, and indicate that there is no formal platform for engaging players from different sectors in the current system.

Mechanisms to share information

The sector specific nature of climate change missions failed to create synergies with each other, and with their respective programmes. The actual implementation of missions is mostly operating in an already established framework of the ministry-specific agendas, and very less cross talks or interministerial consultations are executed (Mayrhofer and Gupta2015). Further, very little information has been communicated to the States by the Central Government about the co-benefi ts approach and SAPCCs largely overlook the idea of co-benefits. Although a common framework for the preparation of SAPCC was developed by the Central government, with the exception of Gujrat and Chattisgarh, SAPCCs have largely failed to recognise climate change as a policy concern (Atteridgeet al.2012). SAPCCs are mostly prepared with assistance from donor agencies or individual consultants and received limited institutional assistance from the federal level (Dubash and Joseph 2016). The lack of communication in part contributed to producing weak SAPCCs with a focus on long and un-prioritised lists of possible implementation actions without a corresponding strategy and without adequate implementation capacity. Overall, successful cooperation for achieving implementation of national missions largely depends on the appropriate communication that fl ows from the central government towards states-focused needs.

Conclusion

India clearly acknowledged the need for domestic action to mitigate climate change impacts, by adopting NAPCC in 2008. This co-benefit approach adopted by the Government of India to address climate problem is an appropriate fit, as it is successful in identifying India’s need to address both climate change and its developmental aspirations. While learning from the existing institutional situation this review highlighted possible institutional limitations that hinder effective implementation of the co-benefit approach of the climate action plan in India. Particularly, incentive mechanisms to promote better co-ordination, information sharing and stakeholder participation are the need of the hour in the Indian context.

With a strong federal (central) governance system in India the climate policy making so far is largely top-down approach. For example, the states have offered very little influence in either the national policy development or India’s approach towards international negotiation (Atteridgeet al.2012). A right mix of both top-down and bottom-up approach needs to be exercised for a meaningful outcome from a climate policy making. To this end, the strengthening of institutional aspects identified in this research are crucial in facilitating and engaging players and institutions at all levels (i.e central, state and local), to effectively implement both national and state level climate action plans.

This article is a part of research project undertaken for the Post Graduate Diploma course on Environmental law and policy offered by the Centre for Environmental Law-WWF and National Law University, Delhi, New Delhi, India.

REFERENCES

Atteridge, A. et al. (2012), “Climate Policy in India: What Shapes International, National and State Policy?” Ambio, 41:68–77.

Dubash, N and A. Joseph, (2016), “Evolution of Institutions for Climate Policy in India”, Economic & Political Weekly, LI (3): 44–54.

Government of India (2008), National Action Plan on Climate Change, Prime Minister’s Council on Climate Change, New Delhi.

IPCC, (2013) “Summary for Policymakers”, in Stocker, T.F.et al. (eds.), Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge and New York, Cambridge University Press.

Jha, V. (2014).The coordination of climate finance in India. Overseas Development Institute and Centre for Policy Research.

Mayrhofer, J.P and J. Gupta, (2015), “The politics of Co-benefits in India’s Energy Sector”, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 1–20.

Nakhooda, S and V. Jha (2014). Getting it together: Institutional arrangements for coordination and stakeholder engagement in climate fi nance. Overseas Development Institute and Report Centre for Policy Research

The World Bank, (2010), Development and Climate Change -World Development Report. Washington