Fostering entrepreneurship can be a here and now policy option to stimulate inclusive growth. Given the potential of entrepreneurship to both reduce poverty and increase incomes, a natural question arises: do special policies work? And what policy options should be pursued?

The case for inclusive growth

Inclusive growth has become a recurring mantra of Indian policymakers. For instance, speaking at the 2009 India Economic Summit, the Indian Prime Minister, Dr Manmohan Singh, asserted India’s commitment to “fast and inclusive growth,” so that, “the benefits of development reach out to all sectors of our population.”

Such calls are not surprising. Indian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been growing at an annual rate of 7 and 8 percent during the last few years, but gains have been uneven despite the doubling of India’s per capita GDP during the 7 years preceding 2007-08. According to a report in the Financial Times, Unicef, the UN’s child development agency, has taken India to task for not using its high economic growth to lift large numbers of people out of poverty. In a comparison likely to rankle, the Unicef noted that India lagged behind China, South Korea, and Singapore, which did better in investing in their people during their economic booms.

Around 80 percent of India’s population lives under two dollars a day, comparable to many sub-Saharan African countries, and twice the corresponding fraction for China’s population. Only two-thirds of Indians are literate, while over 90 percent of the Chinese are. Three-fifths of the labour force is employed in agriculture, but produces less than one-fifth of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and earning are correspondingly far lower. Productivity growth in agriculture has been about a fourth of that in services. This accounts for the disparity in India’s growth. Taken together, these facts indicate that the Indian road to riches thus far has been a kutcha rather than a pucca one.

Entrepreneurship to the rescue

One of the considerations in fostering inclusive growth is that policies aimed at promoting inclusion should not significantly deter growth, especially of the high value added sectors that put India on the global economic map in the first place. This is an instance of the “equity-efficiency” trade-off that economists and policymakers have been concerned with for a long time. One could tax the rich and successful and redistribute to the poor to even out incomes, but this process would reduce the very incentive to become successful. Even the most patriotic Indian would be reluctant to toil for the sake of the tax collector.

The challenge is to enhance economic participation among those at the bottom rungs and facilitate their climb, without tripping up those who are at the higher rungs.

Encouraging entrepreneurship in all sectors is one way to address this dilemma. Entrepreneurs contribute to economic growth by creating new industries, increasing productivity through competition, identifying viable new technologies, and working efficiently and intensively. They serve as a conduit for the commercialisation of knowledge and contribute to economic growth over and beyond the contributions of R&D and human capital. Entrepreneurship also reduces poverty. Indeed, the microcredit revolution aimed at the poor was based on viewing each person as a potential entrepreneur, thereby fuelling “tiny economic engines of a rejected portion of society.” In other words, as a means of wealth creation for the individual and the country, entrepreneurship spans the socio-economic and sectoral spectrum, from villager to venture capitalist, from handicrafts to hardware.

No doubt, factors highlighted elsewhere, such as infrastructure and human capital, are also very important for economic growth. Indeed, they all aid entrepreneurship. However, entrepreneurship, which by its very nature embodies creative approaches to dealing with constraints, can take root even when the above factors are still in the development stages. Having many years of formal education is not a necessary prerequisite for becoming an entrepreneur, and this is highly relevant for a country where a large fraction of adults have minimal education. Sowing the seeds of entrepreneurship among Indian farmers will increase agricultural productivity and rural incomes, hasten industrial transformation, and increase growth. Fostering entrepreneurship is therefore a here and now policy option to stimulate inclusive growth.

Entrepreneurs contribute to economic growth by creating new industries, increasing productivity through competition, identifying viable new technologies, and working efficiently and intensively.

Does special treatment work?

Given the potential of entrepreneurship to both reduce poverty and increase incomes, a natural question arises: does special treatment work? Politicians in all countries revere small-scale enterprises and provide many a subsidy in their name. However, the efficacy of these subsidies seems mixed. One study in the US concluded, “Policies designed specifically to help small businesses do not always have the intended effect,” because they end up benefiting large businesses even more than small businesses, or do not meet their objectives at all. As common sense would suggest, exempting firms below a certain threshold from regulation hinders firm growth because firms near the threshold for exemption, “adjust their size to avoid the more highly regulated market.”

In the Indian context, a team of RAND and Indian School of Business (ISB) researchers recently examined the efficacy of policies in encouraging entrepreneurship in a project supported by the the Legatum Institute. A state-level analysis showed that policies aimed at the micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSME) sector – for instance, total financial subsidy for MSMEs – had little or no impact on the growth of the MSME sector, whereas more general development policies such as expenditure on infrastructure and access to finance had significantly more positive impact on the growth of this sector across states over the last 15 years.

When the research team looked at individual entrepreneurial activity in a predominantly rural, low-income sample, they found that individuals responded better to policies that are likely to have a direct impact on them (such as human capital and technology assistance, and subsidy for capital and financing) while policies aimed at industries (subsidy for taxes, power, and land, industry targeting, incentives for technology clusters, Special Economic Zones, and Single Window Clearance) had little or even a negative effect.

When the effect of the Single Window Clearance (SWC) policy was examined in detail by the research team using firm-level data, they found that it had the effect of reducing the time cost of regulatory compliance across all types of firms. However, enterprises do not appear to have experienced a significant net impact in terms of firm sales and assetsgrowth. SWC reforms may have led only to net entry into the urban/larger unorganised manufacturing sector and growth in the large-scale organised manufacturing sector.

While more research is needed, the results are not strongly in favour of encouragement of small-scale entrepreneurs. These results are consistent with the literature on regulation that suggests that when SWC-type policies have been successfully implemented, their marginal impact on firm growth may still be negligible if other barriers to entry and investment remain high. Evidently, as in the US, small businesses in India also do not always seem to respond to all the policies aimed at them.

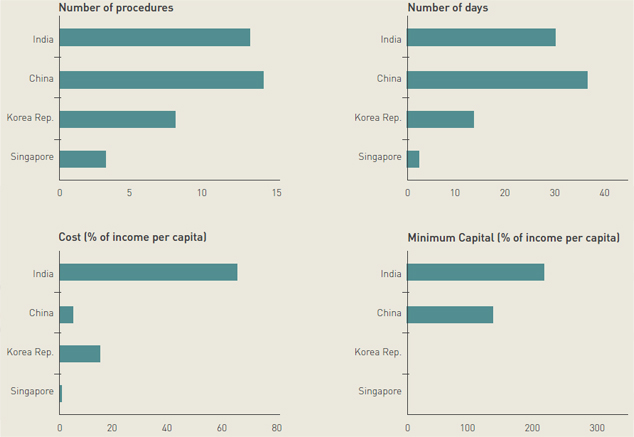

Figure 1: Details on starting a business – Cross-country comparison

Creating an overall business-friendly policy framework is more likely to be effective than subsidies, which might end up in unintended hands or lead to perverse behaviour, providing an incentive for firms to stay small.

What are the policy options?

Given these findings, what policy options could be pursued? The emerging picture suggests that creating an overall business-friendly policy framework is more likely to be effective than subsidies, which might end up in unintended hands or lead to perverse behaviour, providing an incentive for firms to stay small.

While India began dismantling its permit raj since 1991, and has been making it easier to conduct business, it still has a long way to go. In the latest World Bank’s Doing Business rankings, India ranks 133rd (the worst ranking in the list is 183)! How did the countries to which India compared unfavourably according to the Unicef rank? Singapore ranked first, South Korea 19th, and China 89th. It is little consolation that China does not rank that highly; it is still about 45 places above India.

India’s ranking on starting a business is particularly telling. It ranks 169th. (The rankings of Singapore, Korea, and China, are 4, 53, and 151 respectively.)

Figure 1 shows the details. The 13 procedures needed on average to start a business in India take 30 days. The corresponding figures for Singapore are three each. The cost of starting a business in India is over 66 percent of India’s per capita income, and the minimum capital requirement is a whopping 210 percent of per capita income. (The respective figures for Singapore are 0.7 percent and 0 percent.) While everyone would benefit from a lowering of these burdens, the poor would obviously benefit more. It is also not surprising that financing assistance for the poor is an oft-advocated policy.

The effect of entrepreneurship on growth is more markedly positive in developed countries, suggesting that this may, in part, be due to low levels of human capital among developing country entrepreneurs. Indeed, Indian entrepreneurs in the US have the highest incomes among all ethnic groups, and more than 40 percent of this difference with respect to native-born whites could be attributed to human capital. It would be a shame if Indians benefit entrepreneurially from their human capital in other countries but are unable to do so at home, either because they do not have a conducive policy environment or do not have the requisite human capital. As mentioned earlier, for the many uneducated adults, what is needed is not formal education, but training aimed at starting and running an enterprise effectively. A recent study that provided thirty to sixty minute entrepreneurship training to poor, female micro-entrepreneurs in Peru, found improved business knowledge, practices, and revenues.

Clearly, targeted policies aimed at the poor and small businesses will allow entrepreneurship to become an engine of both inclusion and growth. But how little special treatment they would need if the overall policy climate became business friendly and starting a business did not take so much time and money!