Gender discrimination at modern workplaces operates in covert ways through stereotypes which are widely held, static, simplistic generalisations we make about people based on their gender. Societal norms impose certain behavioural expectations on men and women. They are expected to conduct themselves in certain ways. Such stereotypical belief systems percolate all aspects of our lives including work. Jobs are gendered in nature. Certain occupations are considered fit for women while men may be seen as a better fit in some other professions. These segregations are done based on the traits which are often counted as innate in men and women.

Fields like engineering, finance, law are stereotyped as masculine. There are certain qualities that we think are necessary for these jobs which men are believed to possess. Gender stereotypes lead to conclusions that women are deficient in the qualities required for such professions. They might not be actually incapable of delivering such tasks, but stereotypes prompt us to believe that they are not as good as men in these professions.

Such biases that organisations hold against women become apparent when their performances are evaluated. The Shifting Standards Hypothesis proposed and studied extensively by Monica Biernat can clarify this further. When women are given verbal or written feedback about their performance in jobs considered to be masculine in nature, gender bias operates. Stereotypes hold women deficient in traits needed for such jobs. The subjective standard for judging their performance are set quite low. Even if she performs moderately well, she is told that she has performed very well- for a woman!

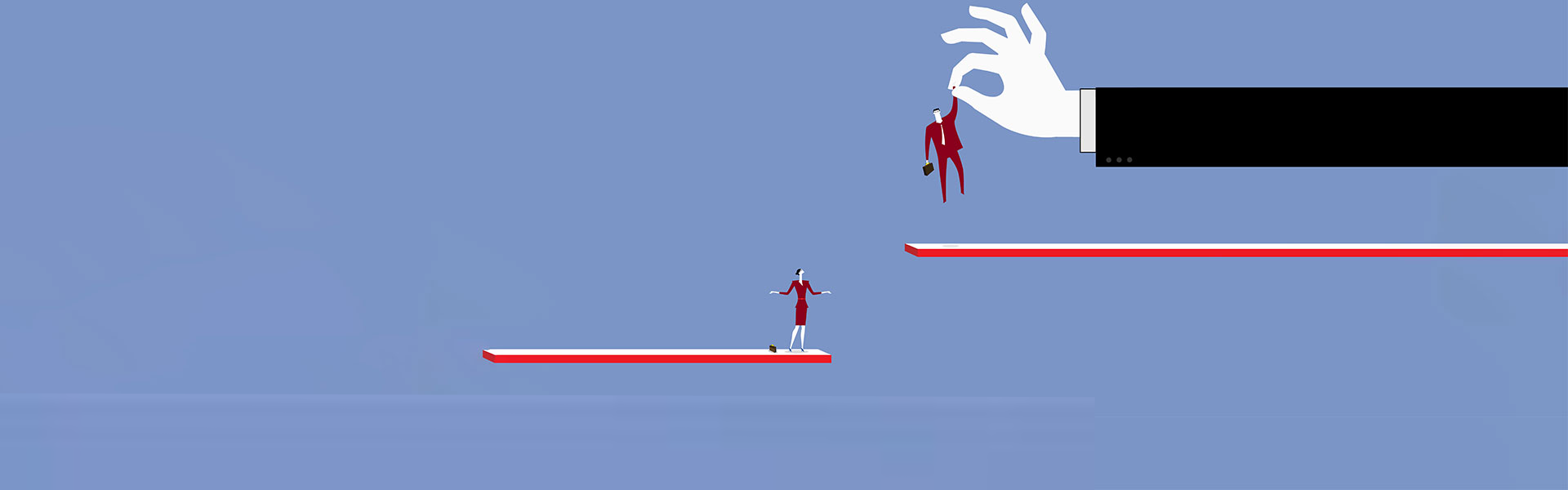

But when an organisation has to select a potential candidate for a salary hike or promotion the standard of judging the performance of women changes. When it comes to promotion, the group that is stereotypically considered deficient, is rated lower than their ‘more competent’ counterpart. This means that women need to show more objective evidence to convince the organisation that they are good compared to men. Even if a woman receives positive feedback in the verbal or written performance appraisal process, it does not guarantee her growth in the organisation. In case of promotion, the threshold is set quite high and is difficult for them to achieve as compared to men. The minimum criterion for assessment is lowered in case of verbal or written feedback but when it comes to promotion, the bar is raised.

Stereotypes Are Products of Socialisation

Gender stereotypes are deep-rooted and are products of socialisation. Research on stereotypes done in the western context may not be directly applicable to India as the socialisation process in India is quite different from that in the West. Research on workplace biases in India must take into cognisance the stereotypical traits that are associated with men and women in India.

In the West high performing women tend to get penalised in various ways. Is a similar trend visible in India? Gender stereotypes prevail everywhere but they operate differently in different contexts.

There are pockets of brilliance in India like the banking sector or civil services where there are many women in senior positions. It is worth studying the intersection between the kind of norms that allow women to succeed in such jobs and the gender socialisation that happens in India.

How to Overcome Gender Biases

While awareness in the organisations about unconscious biases can mitigate their effects, increasing workforce participation of women is of utmost importance in fighting biases. For example, strong, competent women in the workplace are often labelled as cold and unwelcoming. As there is a low representation of women at work, such judgements are based on one’s interaction with a handful of women. But if there is a larger number of women at a workplace the diversity in their behavioural traits can help break the preconceived notions the society holds about working women. Some women can be competent yet welcoming and vice versa.

Gender Diversity at the Workplace

Whether gender diversity enhances productivity in an organisation is often debated. Some research suggests that gender diversity at the workplace improves performance and productivity while others support evidence to the contrary. There is limited research in this area at present. Nevertheless, do we really need evidence that diversity drives performance or productivity for us to accept that gender balance is good for organisations?

As human society progressed our value system has evolved to include equal representation as a quality that every organisation should strive to achieve even if it results in a few years of economic inefficiency (though the link between diversity and economic inefficiency is not empirically established). Gender equality is an important cause and is of significant value. It should not be rejected because of temporary blips (in any) in organisational settings. There is no evidence to suggest that there are innate differences that prevent women from performing well in professions that have traditionally been male-dominated. Proper training can get men and women to be on par with each other even in these professions.

The differences between men and women are often exaggerated, especially when it comes to performing their roles in organisations. Men and women might not be similar in all possible ways. They are different but that does not mean that one is better than the other in all those tasks that are there in an organisational set-up.

About the writer: Debdatta Chakraborty is Research Editor for ISBInsight at the Centre for Learning and Management Practice, Indian School of Business.