Ankur Badonia: What motivated you to work towards the upliftment of rural economy throughout your professional career?

S Sivakumar: There were two key reasons. During my undergraduate days, in the Summer of 1980, I went on a field trip for a rural socio-economic census under the National Service Scheme (NSS). In conversations across homes, farms and street corners, I ran into poverty. Until then, villages only meant visits to grandparents and scenic beauty for me! That’s when I felt I should do something in my life for the benefit of the rural poor.

A year later, during my rural immersion stint at the Institute of Rural Management Anand (IRMA), I stayed with the secretary of the local milk union. Alongside managing a farm, a set of cattle and a retail business with his family, this gentleman also did double duty as the village postmaster and as a tutor. Additionally, he was also the registered medical practitioner for the village. His entrepreneurial energy was striking. But all of it was burning just to keep him where he was, with hardly any wealth creation.

Linking the dots, it occurred to me that the prevailing market structure in India was not conducive for participation by the weaker sections. Could I create a platform to channel this rural entrepreneurial energy and offer the rural population unconstrained access to markets? This was the guiding thought that inspired me to conceive ITC e-Choupal years later.

Could I create a platform to channel this rural entrepreneurial energy and offer the rural population unconstrained access to markets? This was the guiding thought that inspired me to conceive ITC e-Choupal years later.

ITC e-Choupal has been a pathbreaking initiative that has transformed the lives of thousands of farmers. How was the e-Choupal concept envisaged in the first instance?

The export of agri-commodities has been a major ITC business. The markets have evolved a lot over the last two decades. The terms of trade are far more favourable to the farmer today. ITC has been able to innovate and create market structures that have benefited rural communities as much as ITC’s businesses.

In the mid-1990s, the post- World Trade Organization (WTO) global market was opening up. It was a challenge for the Indian agricultural sector operating out of small farms coupled with weak infrastructure to compete with global markets. Under e-Choupal, ITC used the internet to virtually aggregate farms by bringing price discovery to the doorstep of the farmer and bypassing some nodes of the supply chain. This made the whole value chain competitive. Similarly, access to real-time and localised weather forecasts and customised crop management knowledge helped raise productivity, further enhancing competitiveness.

How did ITC select the relevant commodities and geographies to initiate the e-Choupal model?

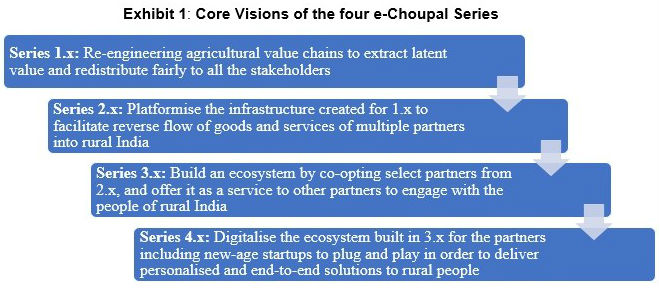

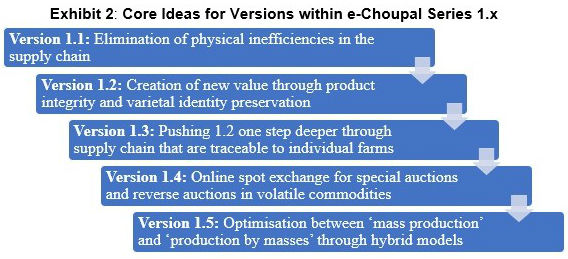

There were two factors governing this selection. The first was economic feasibility and the second, regulatory approvals. For the very first model of e-Choupal, which we call e-Choupal 1.1 now (see Exhibit 1), the idea was to extract latent untapped value. Therefore, we kept the economics simple: focus on one single metric. We called it the transaction velocity– a measurement of supply chain efficiency between farm and factory. If the product moved from farm to factory in one hop, we computed it as a transaction velocity of 1. If the product moved from farm to factory via the mandi, the transaction velocity of 2. If half of all the produce moved directly and half via a mandi, the number was 1.5. The higher the number, the higher the inefficiency.

To shave off this inefficiency, we deployed a model allowing price discovery at the village. Instead of farmers taking products to the mandi and an intermediary taking them to the factory from there, farmers could bring their products to the factory directly. So, to discover prices at the farmers’ doorstep, the internet was brought to the village. We established a price-to-quality linkage through digital quality testing equipment deployed in the village. This shared infrastructure was managed by one of the designated farmers, a Sanchalak.

When we calculated such transaction velocity for all crops across India, we found that soybean had the highest number at 2.72. This meant one could shave off an inefficiency of 1.72. Assuming the cost of all infrastructure that one put in place to facilitate the model to be equivalent to 0.5 units, soybeans offered a net surplus of 1.22 units under the e-Choupal model. This surplus could be redistributed across the farmer, ITC and any other intermediary such as a Sanchalak or Samyojak at the hub of a cluster of e-Choupals.

Instead of farmers taking products to the mandi and an intermediary taking them to the factory from there, farmers could bring their products to the factory directly.

The regulatory challenge was the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Act, which prohibited any transaction outside the mandis. Madhya Pradesh was the largest producer of soybeans and became the first state to relax the APMC Act. It was, thus, the first state where e-Choupal was launched.

Over the years, e-Choupal has gone through four distinct evolutionary series. We tested each phase through our unique methodology of “reimagine the past and reconstruct the future”. Each series was evaluated on its impact. We probed the value chain to identify newer gaps created as a result of the dynamic ecosystems. Subsequently, we renewed our vision; the next series evolved. Within each series, multiple versions kept improving the system incrementally (see Exhibit 1 & 2).

Credit: Created by Ankur Badonia, in conversation with S Sivakumar

Credit: Created by Ankur Badonia, in conversation with S Sivakumar

How do you foresee the integration of Industry 4.0 elements such as cloud computing, AI and automation with agriculture? And what role does the concept of ‘digitaligence’ that you have evolved in ITC Infotech play within agri-tech?

The conventional paradigm for engaging with farmers has been that of ‘last-mile’. Within ‘last-mile,’ knowledge transfer, in the form of ‘global best practices’, happens from central sources cascaded to the farm through a series of trainers. In this paradigm, the ability to personalise knowledge is limited.

However, new technologies such as the internet of things (IoT), remote sensing, machine learning etc. have led to a paradigm reversal. Solutions can now be contextualised to an individual farmer. We have overcome the challenges of reaching out to farmers, identifying their individual needs and co-creating solutions. The latest version of e-Choupal, version 4.0, attempts to integrate many new technologies to achieve these outcomes. We have shifted value creation from the last-mile to the ‘first-mile’ paradigm. This version aims to digitalise the ecosystem built in version 3.x for the partners including new-age start-ups. Our partners can plug and play in order to deliver personalised and end-to-end solutions to rural customers (see Exhibit 1).

The conventional paradigm for engaging with farmers has been that of ‘last-mile’. Within ‘last-mile,’ knowledge transfer, in the form of ‘global best practices’, happens from central sources cascaded to the farm through a series of trainers.

There are solutions such as image processing for identification of diseases, natural language processing for sharing training videos across geographies, hyperlocal e-commerce integrated with external data, etc. Besides our own experiments with these technologies, many agri-tech start-ups are innovating and creating interesting solutions. ITC e-Choupal 4.0 will operate as a digital platform to link such start-ups with the farmers to create end-to-end solutions and deploy them on scale. It will be supplemented by our physical outreach into villages across the length and breadth of India.

The cold chain industry in India has grown at a rapid pace of over 20% in the past five years. As ITC plans to set up its cold chain, do you perceive start-ups and existing cold chain hubs as collaborators or competitors?

Given the dimensions of the opportunity and the specialisation involved, it will be collaborative work. ITC will invest in both ends of the cold chain to ensure product integrity for consumers. For instance, when we were launching ITC Master Chef frozen prawns, our research identified at least 2000 retail outlets in Hyderabad from where consumers would buy frozen products, if only proper refrigerated storage and dispensing infrastructure was available. Only 300 outlets had a reliable infrastructure. With limited volumes of each category at this time, no other player would invest in this leg of the chain.

Similarly, at the other end of the chain, farms also require a similar climate control mechanism to protect the produce from spoilage. In between, we have multiple third-party players providing solutions for transit and storage. Thus, ITC’s investments in the first and the last legs of this chain will complement those of the specialised cold chain logistics players investing along the chain.

ITC recently launched Farmland Potatoes in the retail market. Why potatoes? How does the market perceive such commodity products entering into retail space?

Potatoes are a commodity with highly volatile prices, which is bad both for the farmer and for the consumer. Before the launch of Aashirvaad atta (flour), people could not perceive the difference between loose wheat flour and packaged atta. Then, Aashirvaad came up with the promise of preserved crop identity, thereby transforming a commodity into a value-added product. A speciality product commands consumer franchise. This way, when farmers produce to cater to such specialised demand, the volatile prices associated with commodity products can be avoided.

No matter which product we bring to the market, we strive for full traceability along the entire supply chain, right from its origin.

With this insight, we created multiple variants of speciality potatoes such as low sugar potatoes, high antioxidant potatoes, potatoes for French fries etc. The consumer is ready to pay an extra price. The farmer knows he or she gets a premium as well. No matter which product we bring to the market, we strive for full traceability along the entire supply chain, right from its origin.

You have spent about 30 years of your professional career with ITC. With a booming start-up ecosystem in place, do you think today’s generation of millennials should consider sticking with the same firm for so long?

I have stayed with ITC all these years because it is as entrepreneurial a firm in its DNA as any start-up. The Corporate Management Committee of ITC is like a venture capital body. It believes firmly in the “enduring value” vision, with each business focusing in their area and ideating every year using a rolling five-year planning process. You bring an idea, you own it and you execute it. The ITC support system means higher chances of success. Consider that e-Choupal was a start-up 20 years ago and still is one.

Just as face-to-face interaction with poverty defined the purpose of my professional career, there are multiple triggers today. We still live in a shameful world. What else will you call a world where the bottom 50% of the population has a tiny fraction of the share of the world’s wealth.

Year after year, despite observing the Earth Overshoot Day,1 we technically continue to borrow natural resources from our children and their children by consuming more than we can regenerate. My advice to the next generation is to harness their entrepreneurial energy to make a meaningful difference to this world.

Year after year, despite observing the Earth Overshoot Day, we continue to borrow natural resources from our children and their children by consuming more than we can regenerate.

My takeaways from one of the earliest management development programmes at ISB that I participated in came from the late Professor Sumantra Ghoshal. He recommended developing human capital as a synthesis of intellectual capital, emotional capital and social capital. Be it through an intrapreneurial organisation like ITC, or your own start-up or any other vehicle for that matter, build and leverage your three-dimensional human capital. Change the world!

Surampudi Sivakumar is the Group Head of Agri and IT Businesses of ITC Limited, India. He is the Vice Chairman of ITC Infotech and the Chairman of Technico, an agribiotech company. He is a Member of the Corporate Management Committee of ITC. Sivakumar is well known as the architect of the farmer empowerment initiative ITC e-Choupal. The topper of the Class of 1983 from IRMA, Sivakumar served a farmers’ cooperative for six years before joining ITC in 1989.

Edited by Ashima Sood