Critical differences in board tenures and characteristics between family and nonfamily firms affect firm value and performance, argue Professors Huimin Li, Harley Ryan, Lingling Wang and Baozhong Yang. Their study extends our understanding of the mechanisms that govern family firms and has important implications for founding families, investors and policy makers.

Although corporate charitable contributions are frequent and often substantial, there is no clear evidence on whether these expenditures have positive effects on firm revenues or performance or on shareholder wealth. Proponents assert that corporate giving is consistent with shareholder value maximisation since it is a channel for firms to promote their image to customers and to enhance their standing with regulatory agencies and legislators. Counterarguments suggest that corporate giving can often reflect conflicts of interests between shareholders and managers, where managers support charities based on personal preferences with corporate funds or enhance their personal reputation and social networks. Because it is difficult to measure the benefits that accrue to a firm from charitable contributions, these decisions can reflect the personal preferences of corporate managers, and thus, substantially depart from firm value and shareholder wealth maximisation. Given the ambiguity surrounding the benefits of corporate giving, an understanding of why firms make charitable contributions and what implications such contributions have for shareholder wealth is important.

Profit Maximisation or Private Benefits of Control?

How might corporate giving improve company financial performance? Navarro (1988) posits that there are three dimensions of corporate giving which might enhance firm value, namely, revenue enhancement, cost reduction and tax minimisation. Revenue enhancement represents corporate philanthropy that can be part of or complement a firm’s overall advertising strategy, designed to promote a firm’s image to raise demand for a firm’s product. If this perspective is valid, then we should observe a positive relation between a firm’s giving-to-sales ratio and its propensity to advertise.

Firms can also use charitable contributions to reduce expected costs of government regulatory and enforcement actions. Because firms that rely more heavily on intangible assets or intellectual property and firms in highly regulated or out-of-favour industries are more vulnerable to regulatory and litigation costs, they are more vulnerable to government regulatory and enforcement decisions. It is beneficial for such firms to maintain a good public image and thus make larger charitable contributions.

An alternative perspective for corporate giving is offered by agency theory, which posits that corporate giving does not yield greater revenue or lower costs, but instead represents a diversion of corporate resources, which reduces firm value on a dollar for dollar basis to the extent of corporate giving. Corporate giving can also be symptomatic of broader governance problems at the firm. In their seminal paper, Jensen and Meckling (1976) consider agency costs as a necessary element in any agency relation. They observe that when the owner-managers reduce their firm ownership below 100%, incentives increase for utility-maximising managers to consume more corporate resources since they bear less than 100% of the cost. Thus, a clear prediction of their model is that the private benefits of corporate giving will vary inversely with Chief Executive Officer (CEO) ownership.

Jensen and Meckling (1976) also note that agency costs depend on the tastes of managers and the ease with which they can exercise their own preferences. Thus, private benefits of corporate giving should be positively related to a CEO’s personal preference for charity and negatively related to the strength of a firm’s corporate governance, which places constraints on the CEO’s exercise of preference. Agency theory also predicts a positive relation between corporate giving and the corporate tax rate, as the cost to managers of corporate giving declines with corporate tax rates.

Drivers of Corporate Giving: Some Results

We focus on American Fortune 500 companies and hand-collected giving data from the National Directory of Corporate Giving during 1997-2006. Our findings offer little support for the conventional idea that corporate giving is profit-enhancing. Specifically, we find insignificant results between corporate giving and variables related to profit motives. Although existing theoretical and empirical studies, e.g., Navarro (1988), consider advertising as one of the main motivations for corporate giving, our results fail to support the predicted relation between corporate giving and a firm’s propensity to advertise. On the other hand, we uncover substantial evidence supporting agency theory. More specifically, consistent with Jensen and Meckling (1976), we find that CEO charity connections – a measure of the CEO’s personal preference for charity – increase the likelihood and the amount of corporate giving by 21.4% and 1.5% respectively, whereas a 10% increase in CEO ownership reduces the likelihood and the amount of giving by 40% and 3% respectively.

We use the United States government’s 2003 dividend tax cut as a natural experiment to provide an exogenous source of variation about key CEO attributes. This tax reform reduced the individual dividend tax rate from a maximum rate of 35% to 15% (Chetty and Saez, 2005), and thus increased the cost of CEOs pursuing private preferences toward charitable giving that reduces a firm’s share value, especially when CEO ownership levels are high. Consistent with the implication of this Tax Reform Act for CEO incentives, we find that corporate giving significantly declines after 2003, and this effect becomes stronger as CEO ownership increases.

We find that CEO charity connections – a measure of the CEO’s personal preference for charity – increase the likelihood and the amount of corporate giving by 21.4% and 1.5% respectively, whereas a 10% increase in CEO ownership reduces the likelihood and the amount of giving by 40% and 3% respectively.

We also examine whether corporate giving is incrementally beneficial for a sample of firms with relatively large expenditures on advertising and Research and Development (R&D), as these firms are often assumed to benefit most from charitable contributions. We find no evidence to support this corporate giving incentive; in fact, its relation with advertising and R&D expenditures is statistically insignificant, while CEO ownership and personal charity connections remain significant in explaining a firm’s level of corporate giving. On the other hand, we identify a more muted effect of CEO ownership and a more pronounced effect of charity connections in subsamples of firms where managers are entrenched or able to avoid the discipline of the board of directors. These results indicate that although agency problems of corporate giving are widespread, they are more severe in firms exhibiting weaker corporate governance.

Taking a different approach to evaluating corporate giving, we investigate how corporate giving affects firm value through its impact on cash holdings. Cash reserves can provide funds that allow managers to invest in projects that offer private benefits, but destroy shareholder value. As a result, shareholders may discount the dollar cash holdings of corporations that make charitable contributions, imposing an even greater discount on firms with weaker board oversight.

We fi nd that approximately two out of three firms contribute to CEO-affi liated charities. Moreover, the average cost to a company from such contributions is larger than the combined costs of CEO corporate jet use and other perks and is comparable to a CEO’s promised cash severance payment

We find that corporate giving has a substantial negative impact on firm value through its impact on cash: the estimated marginal value of cash is 8.1 cents lower if a firm raises its corporate giving from the sample median to the 75th percentile level. For firms with non-independent boards where board oversight is expected to be weaker, the negative impact of corporate giving on firm value more than doubles. These findings are consistent with the argument that shareholders anticipate managerial misuse of cash reserves at giving companies, and therefore place a lower value on them.

Corporate Giving and Dividends

To provide a more direct link between corporate giving and shareholder wealth, we (again) use the 2003 Tax Reform Act as a natural experiment. Earlier, we found that corporate giving declines after 2003. Now, we examine whether subsequent reductions in corporate giving lead to dividend increases. Specifically, by focusing on firms that make charitable contributions in 2002, we investigate how changes in charitable contributions affect dollar dividends in 2004. We find that a US$1 million reduction in corporate giving after the tax-cut year is associated with an increase of at least US$6.4 million in dividends. Thus, our experiment shows that dividends (or alternatively, shareholder wealth) increase after the Tax Reform Act of 2003, consistent with senior managers reducing their consumption of the private benefits of control as their personal cost rises. One implication of this finding is that a tax policy that increases the costs of insiders pursuing private benefits of control leads to greater shareholder wealth maximisation. Having documented that corporate giving represents an agency problem, we conduct a series of tests to address why and how corporate giving destroys firm value. First, we examine whether corporate giving offers opportunities for managerial rent extraction by investigating the frequency and level of corporate contributions to charities where CEOs hold positions as trustees, directors or advisors (henceforth, CEO-affiliated charities). We find that approximately two out of three firms contribute to CEO-affiliated charities. Moreover, the average cost to a company from such contributions is larger than the combined costs of CEO corporate jet use and other perks (Yermack, 2006) and is comparable to a CEO’s promised cash severance payment (Rusticus, 2006). Furthermore, CEO-affiliated charitable contribution levels decline if the CEO’s financial interests are more aligned with the interests of shareholders. These findings suggest that corporate giving is not solely determined by firm value maximisation, but instead is a channel that serves managerial private interests.

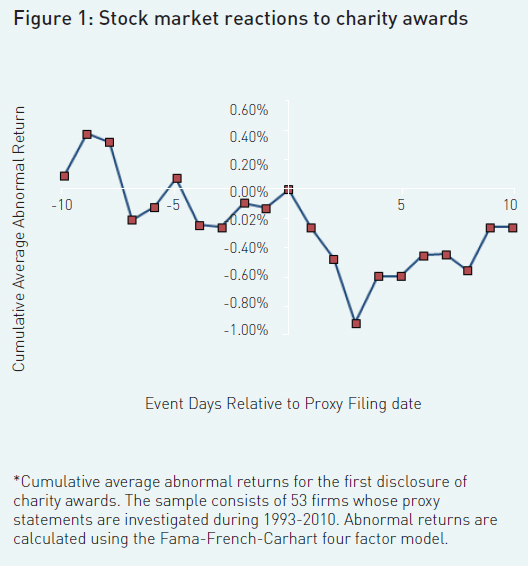

Second, we conduct an event study of the first disclosure by a corporation of “charity awards” to gauge how investors perceive charitable contributions where the charities have ties to company executives and directors. In revising the disclosure rules on compensation in 1992, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recognised such awards as a form of compensation and mandated that firms report them in proxy statements. Figure 1 documents a three-day cumulative abnormal return (CAR) of -0.87% (p-value = 0.014) for firms that report charity awards for the first time during 1993-2010. This wealth loss exceeds the nominal value of the announced charitable award programmes, suggesting that shareholders take into account the expected future contributions on these announcements or reduce their assessment of the quality of a giving firm’s overall governance.

Furthermore, CEO-affi liated charitable contribution levels decline if the CEO’s fi nancial interests are more aligned with the interests of shareholders. These findings suggest that corporate giving is not solely determined by firm value maximisation, but instead is a channel that serves managerial private interests.

Donating to Charities or Company-sponsored Foundations?

We separately analyse the determinants of annual direct corporate giving to charities and contributions to charitable foundations to evaluate the seriousness of an agency problem associated with these two channels of corporate giving. Foundations are tax-exempt non-profit organisations that receive irreversible donations from their sponsoring companies. The critical factor for these foundations is the separation between the economic affairs of shareholders and those of the foundations. This separation negates any shareholder claim on any donations transferred to the foundations, and therefore poses a classic agency problem for firms that make charitable contributions through foundations.

Consider the case of the Lehman Brothers Foundation, for example. Although its sponsoring company was liquidated in 2008, the foundation still exists under the name of the Neuberger Berman Foundation. In the year of liquidation, the foundation had a market value of assets of US$23.4 million, which was not distributed to company shareholders. As of November 2012, the foundation still uses that asset for philanthropic purposes.

In our empirical analysis, we find that giving to foundations increases with both a CEO’s charity connections and weaker corporate governance, while annual giving to charities increases with stronger corporate governance. These results suggest that the adverse impact of corporate giving on firm value is largely due to sizeable, irrevocable donations to corporate charitable foundations.

Thus far, our results indicate that CEOs realise personal benefits from corporate giving. However, these benefits could still be part of an optimal CEO compensation contract. Specifically, do boards reduce manager compensation for any corporate contributions that benefit them? So we study the relation between CEO compensation and corporate giving. We document that a 10% increase in giving is associated with a US$523,500 rise in CEO compensation. This evidence indicates that the probability of a company paying abnormally high CEO compensation is significantly higher when companies make large charitable contributions.

What specific channels of CEO entrenchment help explain the above relationship between corporate giving and excess CEO compensation? Cespa and Cestone (2007) argue that CEOs use corporate resources strategically to build ties with stakeholders to receive favourable treatment during future contract renewal or turnover decisions. We propose that a more direct form of entrenchment occurs if CEOs use firm donations to support independent director charitable interests. Specifically, we examine whether charitable causes supported by corporate giving overlap with independent directors’ charitable interests and then evaluate the effect of this alignment on CEO compensation. We find a 69% overlap with the interests of independent directors, indicating that a strategic use of corporate giving is to support independent directors’ charity interests and thereby strengthen their ties to a CEO. We also find that this particular alignment of charitable interest is positively associated with excess CEO compensation. These results suggest that corporate charitable contributions advance CEOs’ private interests.

Implications

While our evidence is consistent with the predictions of agency theory, it is likely that in many instances corporate giving does benefit shareholders. However, such cases appear to be less frequent and the benefits are more indirect and difficult to measure, while charitable contributions definitely represent a direct cost to shareholders. Taken together, the results of this study document another important mechanism for managerial rent extraction, especially when CEOs are entrenched.

The evidence in our study raises serious concerns about the decision process surrounding corporate charitable contributions. One implication of this study is that securities regulators should consider requirements to promptly disclose insider-affiliated corporate giving, given that it can adversely affect minority shareholders. In fact, legislators and government agencies in the US have long recognised the agency problems of corporate philanthropy. However, a lack of concrete evidence of managershareholder conflicts of interest on this issue helped opponents resist regulatory reforms. Hopefully, studies like the current one will help to tip the scales towards future reform.

Further Reading

Cespa, G and G Cestone (2007). “Corporate Social Responsibility and Managerial Entrenchment”, Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 16, 741-771.

Chetty, Raj and Emmanuel Saez (2005). “Dividend Taxes and Corporate Behavior: Evidence from the 2003 Dividend Tax Cut”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 791-833.

Faulkender, Michael and Rong Wang (2006). “Corporate Financial Policy and the Value of Cash”, The Journal of Finance, 61(4): 1957-1990.

Jensen, Michael C and William H Meckling (1976). “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure”, Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4): 305-360.

Navarro, Peter (1988). “Why do Corporations Give to Charity?” Journal of Business, 61 (1): 65-93.

Rusticus, Tjomme O (2006). “Executive Severance Agreements”, Working Paper.

Yermack, David (2006). “Flights of Fancy: Corporate Jets, CEO Perquisites, and Inferior Shareholder Returns”, Journal of Financial Economics, 80, 211-242.