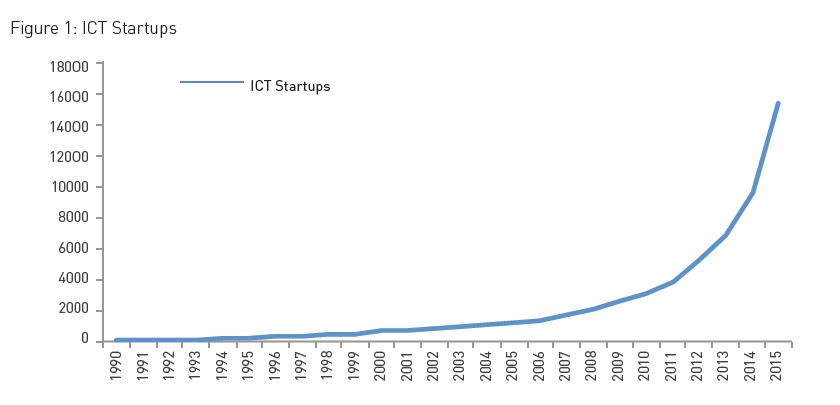

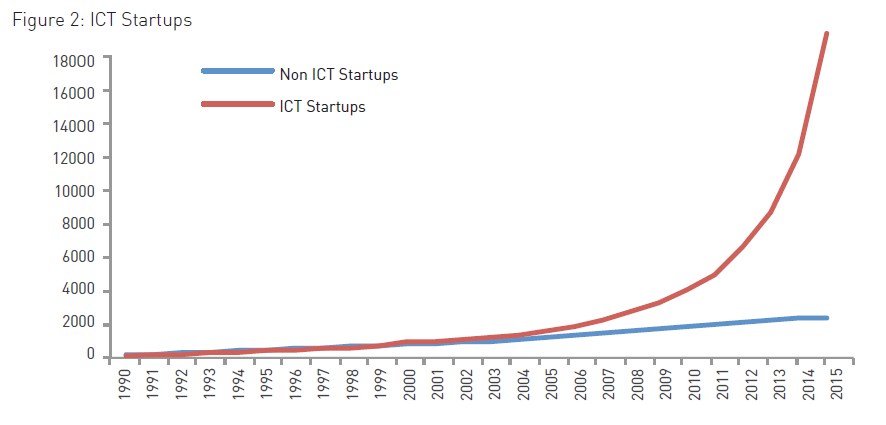

From virtually being non-existent in 2000, India had the third largest number of start-ups behind only the US and the UK in 2016 (see Figure 1). Most of this activity can be attributed to increased startup activity in the Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) sector (see Figure 2). What is even more impressive is the fact that India ranks third in terms of successful exits with almost all the exits happening in the ICT sector (Economic times, 2016). In this article, based on an analysis of 15,302 startups from 1990-2015, we trace the evolution of ICT start-ups and provide some insights on the sectoral and geographical patterns in the industry, and identify some of the factors behind the emergence of these start-ups.

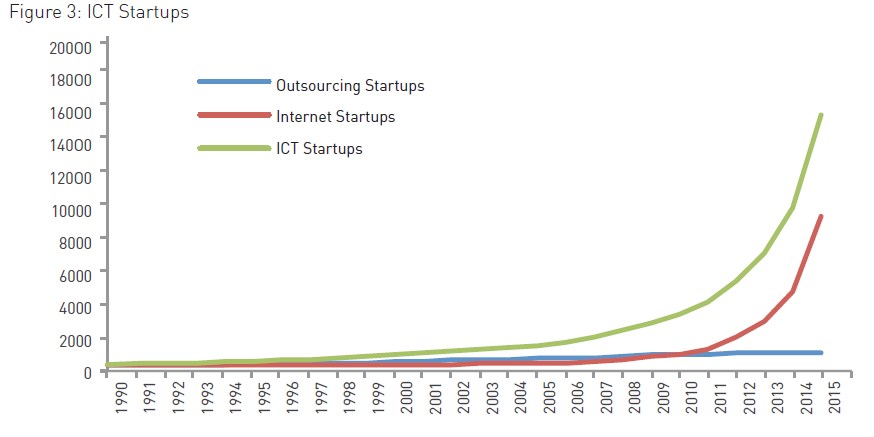

The plateauing demand for software services coupled with the rapid increase in Internet and mobile penetration in India appears to have induced more start-up activity in the Internet sector.

Contrary to popular perceptions, a whopping 95% of the 15,302 ICT start-ups are not in the business of outsourcing. About 60% are in the Internet sector, most of which focus on Indian markets. Interestingly, whereas outsourcing start-ups have not grown as much as the other types of startups in the ICT sector, (see Figure 3) other types of start-ups including start-ups in the Internet subsector, have grown rapidly especially after 2009. The plateauing demand for software services coupled with the rapid increase in Internet and mobile penetration in India appears to have induced more start-up activity in the Internet sector. To put these facts in perspective, although the Indian software exports grew to about $82 billion in 2015-16, its growth during the last five years between 2007-08 and 2013- 14 was only 11% compared to the 33% growth rate between 2000-01 and 2006-07. In parallel, the internet and mobile penetration in India exceeded that of even the US in 2007 and continued to grow at a rapid rate (Indiastat and Wall Street Journal, 2015). These patterns seem to have coincided with the rapid growth in Indian ICT start-ups, especially in the internet sector.

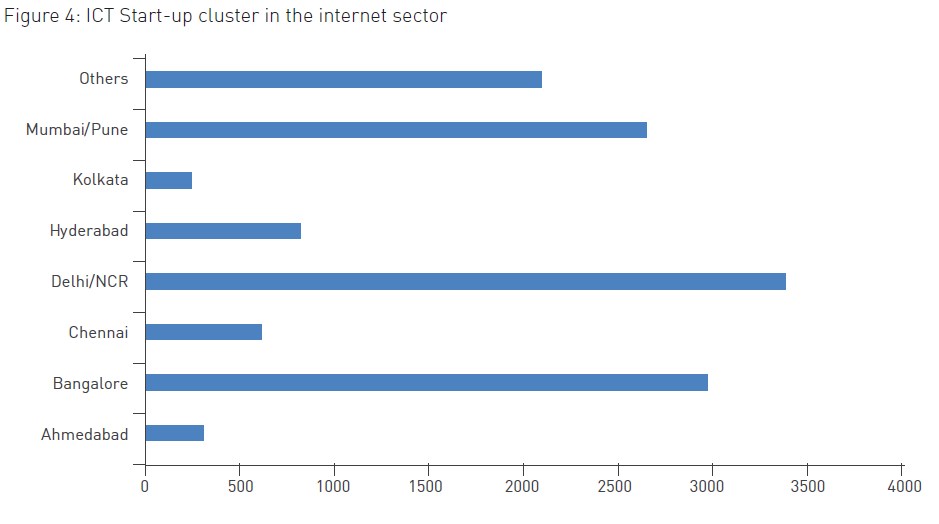

The regional patterns of the industry suggest that the industry is significantly clustered in three regions. Close to about 2/3rd of all start-ups in this sector are in just three regions: NCR, Mumbai-Pune, and Bangalore.

The regional patterns of the industry also suggest that the industry is significantly clustered in three regions. Close to about 2/3rd of all start-ups or about 10,298 in this sector are in just three regions: NCR, Mumbai-Pune, and Bangalore (see Figure 4). Notable absentees from this elite group of cities are Chennai and Hyderabad – two other cities which are often associated with contributing to software exports from India in large numbers. Prior work has shown that manufacturing industries typically cluster in one or more region for two reasons. The first is because of the existence of one or more of the following in a region: regional advantages that implicitly confer benefits to start-ups and firms in certain industries, the presence of ‘production externalities’, due to which start-ups somehow benefit from proximity to other firms in the same industry or related industries, and proximity to consumer suppliers or pecuniary industries which lower the transportation costs to supply or distribute products. The second is related to the phenomenon of spawning, a process by which parent firms within the same industry generate start-ups. This spawning process not only creates these clusters but also sustains them. In the early stages of an industry, regions serendipitously have one or more successful pioneers or early entrants that were successful. As these successful pioneers generate successful spinoffs, which also locate in the same location as their parent, industries start to cluster in those regions.

The ICT sector, unlike many others, is one that allows different types, of entrants to enter, and prosper. This is because unlike manufacturing based industries, this industry does not require high set up costs to set up manufacturing units or to distribute products to the different corners of the country. The fact that a non-manufacturing industry such as the ICT industry exhibits significant amount of clustering is by itself an interesting phenomenon that merits further exploration. We hence explored some of the plausible factors that might explain why this sector exhibits a significant amount of clustering.

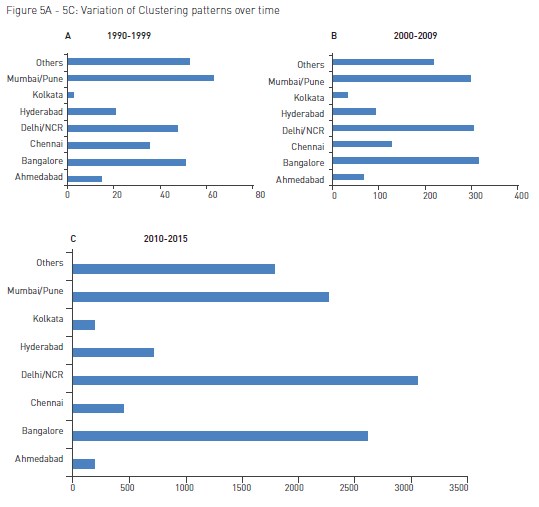

We first explored the age of these clusters by exploring if these clustering patterns varied over time (see Figures 5A-5C) and found that the Mumbai-Pune region first emerged as the largest cluster between 1990 and 1999 when the start-up activity itself was very nascent and when very few start-ups were prevalent in India. In the second period between 2000 and 2009, in which there was a moderate growth in start-up activity, the NCR region and Bangalore caught up with the Mumbai-Pune region so much so that these three regions equally contributed to the start-ups activity in India during this period. The third period between 2010 and 2015 interestingly witnessed the pulling away of the NCR region and surged ahead of Bangalore and the Mumbai-Pune region.

The ICT sector, unlike many others, is one that allows different types, of entrants to enter, and prosper. This is because unlike manufacturing based industries, this industry does not require high set up costs to set up manufacturing units or to distribute products to the different corners of the country.

We then explored if the number of startups in a region are correlated with other regional characteristics such as the economic munificence, innovation patterns or funding opportunities in those regions. To this end, we first explored if the distribution of per capita GDP growth looked like the regional patterns of start-up activity (see Figure 6) and found them to be different. Whereas the growth rates were the highest in Bangalore between the years 1993-2007, the patterns between 2007-2010 reflected the presence of other cities like Kolkata in which start-up activity in the ICT sector was very sparse. These patterns thus at least prima facie rule out the fact that start-ups tend to cluster in regions which generally have more economic opportunities.

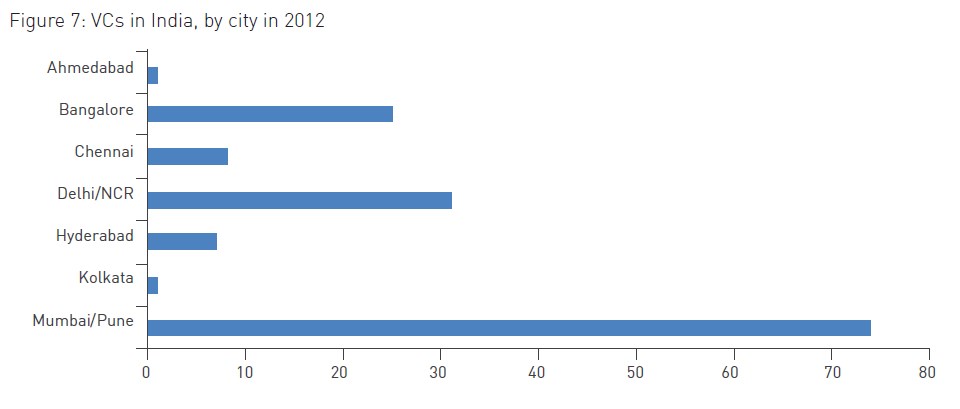

Next, we explored if the clustering patterns were correlated with the innovation patterns in India. To this end, we explored if the regional patent filing patterns with the Indian Patent office based on the location of the assignee to whom patent were granted were correlated with the regional distribution of start-up activity in India. We found that the patenting patterns were quite different from the clustering patterns alluded to above. For instance, Karnataka and Maharashtra were dominant innovators, other states such as (united) Andhra Pradesh or Tamil Nadu that were equally dominant did not exhibit as dense clustering patterns as Maharashtra (Mumbai-Pune) or Karnataka (Bangalore). These patterns rule out the fact that the innovation patterns in India at least partially explained the patterns of clustering of startups in the ICT sector. We then explored if the differences in VC funding opportunities reflected the clustering patterns of start-ups in the ICT sector. Figure 7 presents the regional distribution of VCs in India in 2012 when NCR has already emerged as the dominant cluster of start-ups in the ICT sector. Contrary to the clustering patterns between 2010 and 2015, Figure 7 shows that Mumbai-Pune had the maximum number of VCs followed by Bangalore and NCR. Stated otherwise, while VCs also tend to cluster in the same three regions, Mumbai-Pune appear to be the dominant VC cluster whereas NCR is the dominant start-up cluster. Thus, these patterns too do not explain the patterns of start-up clusters in the ICT sector. While these analyses are by no stretch causal, the mere absence of correlations would at the least suggest that often presumed causes for the existence of start-up clusters, most of which are based on the existence of certain regional characteristics, would fail the smell-test and plausibly reject those arguments.

Finally, we traced the source of each start-up by patterns were quite different from the clustering patterns alluded to above. For instance, Karnataka and Maharashtra were dominant innovators, other states such as (united) Andhra Pradesh or Tamil Nadu that were equally dominant did not exhibit as dense clustering patterns as Maharashtra (Mumbai-Pune) or Karnataka (Bangalore). These patterns rule out the fact that the innovation patterns in India at least partially explained the patterns of clustering of startups in the ICT sector.

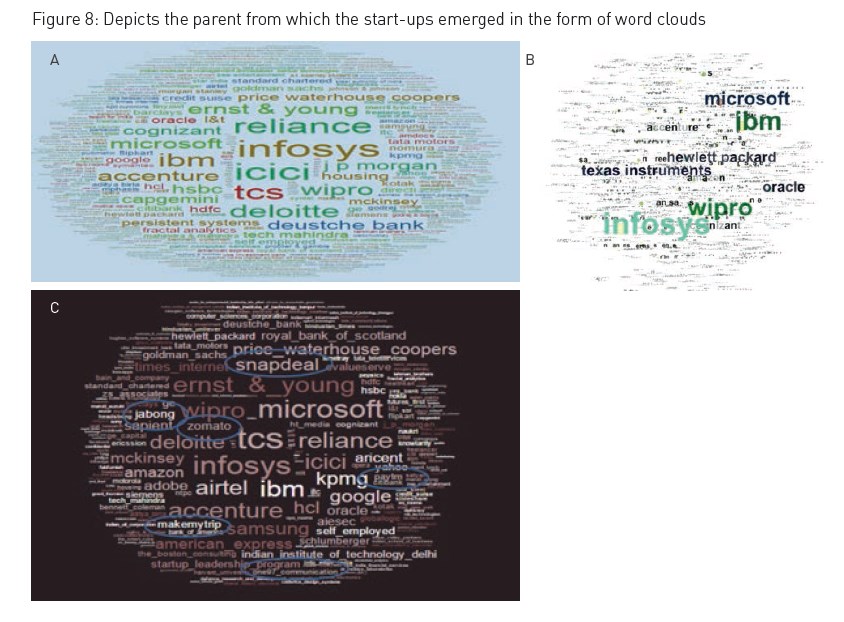

We then explored if the differences in VC funding opportunities reflected the clustering patterns of start-ups in the ICT sector. Figure 7 presents the regional distribution of VCs in India in 2012 when NCR has already emerged as the dominant cluster of start-ups in the ICT sector. Contrary to the clustering patterns between 2010 and 2015, Figure 7 shows that Mumbai-Pune had the maximum number of VCs followed by Bangalore and NCR. Stated otherwise, while VCs also tend to cluster in the same three regions, Mumbai-Pune appear to be the dominant VC cluster whereas NCR is the dominant start-up cluster. Thus, these patterns too do not explain the patterns of start-up clusters in the ICT sector. While these analyses are by no stretch causal, the mere absence of correlations would at the least suggest that often presumed causes for the existence of start-up clusters, most of which are based on the existence of certain regional characteristics, would fail the smell-test and plausibly reject those arguments. Finally, we traced the source of each start-up by exploring where the founders of each start-up were from. Figures 8A-8C, depict the parent from which the start-ups emerged in the form of word clouds, which the font size of the parent depicting how frequent such parents were likely to spawn a start-up. Figure 8A, which depicts the word cloud for Mumbai- Pune region shows that large business houses were the main source of the start-ups in that region. These business houses do not appear to be concentrated in any one industry, although many of them appear to be large IT firms or multinational banks or investment banks. Given that this region was dominant in the first period between 1990 and 1999, this implies that the large business houses might have been the source of first set of start-ups in this sector.

While VCs also tend to cluster in the same three regions, Mumbai-Pune appear to be the dominant VC cluster whereas NCR is the dominant start-up cluster.

Figure 8B shows the word cloud for the Bangalore region. It shows that large IT firms both Indian and multinationals were very prolific in generating startups. The world cloud for the NCR region appears to be a confluence of those of Mumbai-Pune and Bangalore regions albeit with differences. One standout feature of this region appears to be the spawning activity of other start-ups within the same sector. Given that Bangalore and NCR regions were dominant in the second and third periods between 1999 and 2015, this implies that the large IT firms and start-ups were the sources of the subsequent set of start-ups in this sector. Also, given that the start-ups spawning activity is very recent, we also argue that this activity represents the third wave of start-ups in this sector.

The world cloud for the NCR region appears to be a confluence of those of Mumbai-Pune and Bangalore regions albeit with differences. One standout feature of this region appears to be the spawning activity of other start-ups within the same sector.

In conclusion, the emergence of start-up activity in the ICT sector has shown an exponential increase after 2010. Two trends stand out from this analysis. These trends also explain the emergence of ICT start-ups and the regional concentration of start-ups in this sector. The first is the plateauing of demand for IT services and the rapid penetration of Internet and mobile phones in India that plausibly resulted in more start-ups exploring the relative nascent Internet opportunity, most of which catered to the domestic demand rather that exporting IT services overseas. The second is the absence of any link between regional characteristics and the clustering patterns of start-ups within this sector. Our analysis suggests that it was the process of entrepreneurship that created and sustained clusters rather than the clusters which embody certain unique regional characteristics attracting entrepreneurs to cluster in a location. The latter especially has significant policy implications. Governments and cities that invest in creating manmade clusters might have to pause a bit and think about whether such policies may spur faster economic development through entrepreneurship.