Governments, regulators and electricity utilities around the world are today seriously engaged in efforts to manage consumer electricity consumption. The need to achieve energy efficiency among various other reasons is leading to such initiatives that attempt to change consumer energy behaviours. Anant Sudarshan offers an analysis based on research in the United States and India related to the potential of behavioural interventions with respect to consumption of electricity and some of the limitations of this approach.

Framing policy to tackle environmental challenges frequently involves dealing with the difficult problem of changing consumer behaviors.

To change behavior – assuming there is a good reason to do so – requires figuring out how people respond to different incentives and policy instruments. When it comes to modifying consumption behaviors, by far the most commonly used tool is to change the prices people pay. Yet while straightforward in theory, changing prices is often neither politically nor administratively easy to implement. And where subsidies are involved, it may also become a very high cost policy tool.

The focus on price as an instrument to change behaviour comes from classical economic models of rational choice and utility maximisation. Yet even within traditional models of decision-making, we sometimes forget that while price is one factor that determines how we behave, it is not the only variable that influences our decisions.

In recent years, behavioural economists and psychologists have systematically documented a variety of behavioural tendencies that explain human decision-making. Experiments have shown that people tend to change behaviour based on what their peers do (Schultz et al., 2007; Cialdini, 2007), they often pay limited attention to choices and are overwhelmed by excessive choice (Iyengar and Lepper, 2000), their decisions may be strongly influenced by default choices (Abadie and Gay, 2006) and they may resist changes from the status quo (Hossain and List 2012). Research has also documented that simply modifying how information is framed or presented can systematically change the way people respond (Tversky and Kahneman, 1981; Kahneman, Knetsch, and R. H. Thaler, 1991).

As an example, Pichert and Katsikopoulos (2008) present evidence from the field and from experiments demonstrating that the fraction of people enrolling in green energy plans is much higher when these options are made opt-out, rather than opt-in. An early and influential study in the field of medicine showed how much the framing of information matters. McNeil et al. (1982) showed that given a choice between surgery and radiation therapy, describing surgery outcome statistics as a 90% survival rate yielded a significantly higher preference for surgery than when described as a 10% mortality rate.

Empirical studies of this type, and their associated theory, have opened up the possibility of using behavioural characteristics to change consumer actions without necessarily modifying their financial incentives. In turn, this opens up an intriguing set of options for policy-makers that might achieve the same objectives as imposing taxes and subsidies. These tools are often called ‘nudges’ in reference to their attempt to gently guide behaviour in desired directions. While nudges have been studied in a variety of policy settings including healthcare choices and savings behaviour (Handel, 2013; Beshears et al., 2011), arguably their most widespread application has involved changing household energy behaviours.

In this article, I discuss how behavioural techniques have been applied in one crucially important setting – demand management of household electricity consumption. I look at their potential as well as limitations and describe how researchers are using innovative field experiments to learn more.

Energy efficiency is only one of the reasons for wishing to change consumer energy behaviours. Utilities have also tested and introduced programs to reduce peak hour consumption through dynamic and real time pricing. Such programs seek to minimise the inefficiencies introduced by using static prices to sell electricity even though the cost of supply varies with the time of day.

Why Manage Electricity Demand?

To begin however, it is useful to understand why we might even want to change the electricity consumption of high-demand households, and why this might sometimes be a good thing.

Governments, regulators and electricity utilities around the world are today seriously engaged in efforts to manage consumer electricity consumption. These initiatives generally attempt to reduce consumption by high consuming homes, either on average or at certain times of day.

At first glance, this might seem rather odd. What possible motivation might exist for a utility that makes money selling electricity, to try and reduce the quantity sold?

In the United States, many demand management programs have been explicitly linked to efforts to increase energy efficiency (Gillingham et al., 2006 describes some of these efforts). The ‘Energy Efficiency Gap’ hypothesis, a topic of many years of research and debate (Jaffe and Stavins 1994; Allcott and Greenstone 2013), suggests that consumers often make sub-optimally low investments in energy efficient appliances – even where these appliances would save them money. Utilities have the opportunity to change this by providing consumers information about energy efficient goods, introducing promotions or incentives and so on. In turn, consumers might save money and use less energy with additional benefits for society including lower air pollution and mitigating the risks of climate change.

For this reason, regulators in the United States have frequently encouraged or required utilities to run aggressive demand management initiatives. Regulatory changes known as “decoupling” have been used to separate utility profits from the quantity of power they sell, allowing them to undertake such initiatives.

Energy efficiency is only one of the reasons for wishing to change consumer energy behaviours. Utilities have also tested and introduced programs to reduce peak hour consumption through dynamic and real time pricing (Wolak, 2011). Such programs seek to minimise the inefficiencies introduced by using static prices to sell electricity even though the cost of supply varies with the time of day.

Demand management is important in developing countries also. Although much of the published literature focuses on the United States (Sudarshan, 2013; Wolak. 2011, Arimura et al., 2009), the rationale for such programs is arguably even stronger in developing countries such as India. In the Indian context several additional factors motivate efforts to change energy consumption patterns. These include distortionary tariff cross-subsidies (Singh, 2006), rationing and blackouts owing to crippling supply shortfalls. In the case of decentralised power generation, fuel price shocks may motivate suppliers to encourage their consumers to use less power.

For all these reasons, the policy importance of demand side management in India has been growing, underscored by the passing of an ambitious Energy Conservation Act in 2001 and the initiation of a National Mission for Enhanced Energy Efficiency by India’s Ministry of Power in 2010-11. In its most recent five-year plan, India’s Planning Commission proposed allocating over 50 million dollars to enhance the capacity of state utilities to implement demand side management programs.

Instrument Choice and Behaviour Change

If we accept the argument that it might sometimes be socially beneficial to get high consumers of electricity to reduce demand, the question that follows is how to achieve this?

Clearly one way to do so, is to raise electricity prices. However tariff changes can be politically unpopular and consequently difficult to introduce. It is therefore useful to also consider other techniques. In particular, policy makers might want to know how raising prices compares to other ways of changing behaviour, including behavioural interventions or ‘nudges’.

Recent research in the United States and India has allowed us to begin to answer these questions, revealing both the potential of behavioural interventions and some of their limitations.

How Do Consumers React to Real Time Data?

In 2010, researchers from Stanford University conducted a large field experiment in partnership with Google Inc. involving over 1700 households all over the United States (Houde et al., 2013). This study attempted to investigate whether household electricity consumption habits changed, when provided minute by minute real time information on usage.

The theory behind this idea is quite simple. Unlike mobile phones for example, we know very little about how much electricity we use on a day to day basis and how this changes. Most people obtain at most one electricity bill a month. This aggregate information on usage and cost makes it hard to figure out when and how we spent what amount of electricity.

In addition, because continuous feedback on our consumption of electricity is normally unavailable, it is plausible that the salience of our energy behaviours is reduced. Put another way, we cannot manage what we do not notice, and we may not notice our electricity costs adding up.

To test this proposition, over 1700 households were randomly divided into a treatment group and a control group. Treatment households were provided a free electronic meter connecting to an online portal (Google Powermeter) that displayed their energy consumption every minute. The portal also allowed them to compare how much they used from one day to the next and to set targets if they wished. Control households were metered, but not given access to the portal for six months.

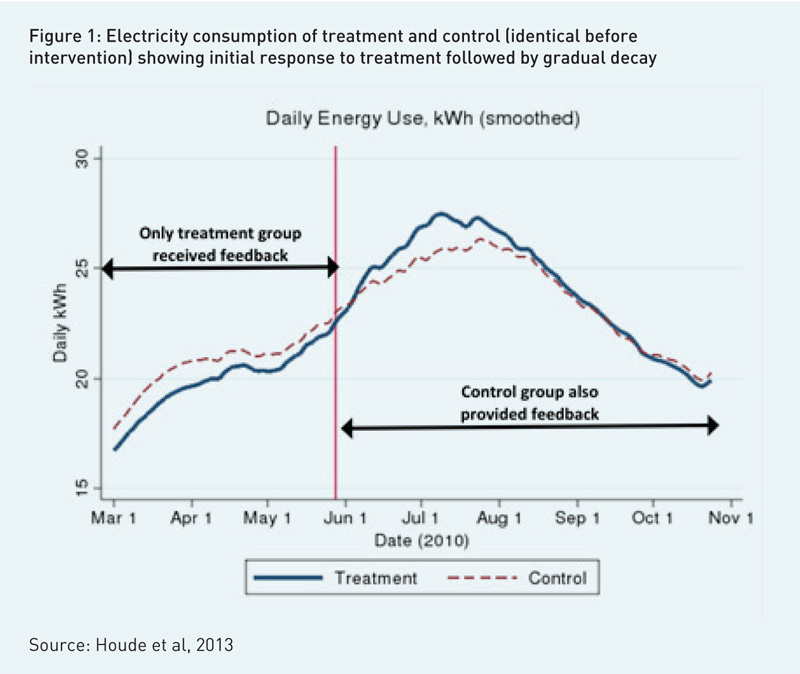

The results were interesting. Almost immediately after being given real-time feedback on consumption, households receiving this information reduced daily consumption by about 8 percent on average relative to control homes. Over time however, this response began to decrease and after about three months their consumption was similar to the control population. When these control households were finally given access to the same information the pattern repeated. Figure 1 compares the electricity consumption of the two groups, over the period of the experiment.

Almost immediately after being given real-time feedback on consumption, households receiving this information reduced daily consumption by about 8 percent on average relative to control homes. Over time however, this response began to decrease and after about three months their consumption was similar to the control population. When these control households were finally given access to the same information the pattern repeated.

The good news is that a very low cost intervention – provision of information on consumption – changed consumption significantly without prices moving. The bad news was that the effect faded after a while.

Could behavioural techniques be useful on a sustained basis? To answer that, let’s look at one more study that also studied the effect of providing a different type of nudge.

How do Consumers React to Comparisons with Peers?

O-Power is a fast growing start-up (indeed now a more grown-up company) in the United States. This company came up with an interesting idea for electricity utilities looking to reduce household electricity consumption. The company mailed a letter with the electricity bill to all utility consumers that contained a comparison of the household’s consumption of electricity to the average household consumption in the region. Customers using less than the regional average were `rewarded’ with a smiling face.

This simple design is based on a rich history of work in the psychology and behavioural economics exploring how social norms influence human behaviour (Cialdini, 2007; Schultz et al., 2007). Laboratory and field experiments have shown that people may modify behaviour when exposed to comparisons with their peers (the definition of a peer varying by context). One explanation for why this occurs, originating from the psychology literature, is that people seek to adhere to `social norms’, which are prescriptions of behaviour regarded as socially desirable or normal. On this basis, when households are informed that they are consuming electricity at a level very different from their peers, they incur a psychological cost. In order to minimise this cost, they change behaviour.

The results of exposing households to peer comparisons in the O-Power studies have been extensively studied (Allcott and Rogers, 2014). This research has documented that by sending households letters comparing their consumption to their peers resulted in a 1 to 2 percent decrease in electricity used. Furthermore, this effect can be sustained over a number of years even after discontinuing mailers (provided that the initial peer comparisons were continued for at least two years). While the percentage impacts on consumption are small, the costs of such an intervention are low and can be scaled up easily. Allcott and Rogers (2014) estimate the cost of a saved kilowatt-hour through this nudge to be less than 2 cents, against electricity prices of over 10 cents. These numbers are below many alternative energy efficiency programs in the United States (estimated at about 5 cents per KWh by an ACEEE study).

Applying Social Norms to an Indian Context Can social norm based treatments work in India? To answer this question, a recent study provided apartment dwellers in Ghaziabad, weekly comparisons of their electricity consumption relative to their neighbours (Sudarshan, 2013). The study also estimated the response of households to changes in electricity tariffs. This allowed for a comparison of the effectiveness of the behavioural nudge, relying on information alone, with changing prices for electricity.

The results were compelling. Sustained over an entire summer season (May to August), households who were sent these report cards, reduced electricity consumption by over 8 percent on average. The finding thus replicated (with somewhat larger impact) evidence from the United States.

Even more intriguing, these households were arguably more responsive to these comparisons than they were to changes in the price of electricity. Because households in this study consumed electricity from two sources (utility power and backup diesel based power) that were each separately billed and metered, it was possible to estimate the price elasticity of households as well. This experiment showed that while households did adjust consumption in response to tariff changes, the price elasticity was relatively low (-0.13). Other studies in both the United States (Reiss and White, 2005) and India (Filipini and Pachauri, 2002) have also found that urban and relatively high income households may have low price elasticity.

This evidence suggests that reproducing the short run response of consumption to the behavioural nudge (which is based only on providing information), through price changes, would have required a 65 percent tariff increase. Although one study may be insufficient to draw strong conclusions about the relative response of populations to different instruments, nevertheless these results help to underscore the potential of behavioural techniques in this setting.

Could Behavioral Instruments Provide Low Hanging Policy Fruit?

The evidence I discussed in previous sections helps indicate that behavioural techniques can marginally shift consumption choices. One might wonder however whether policy instruments that generate small responses of the order of a few percent of consumption are really worth thinking about. After all, India produces too little energy so isn’t increasing supply what we should focus on? What would we gain from a modest reduction in demand, whether from increasing energy efficiency or changing behaviours?

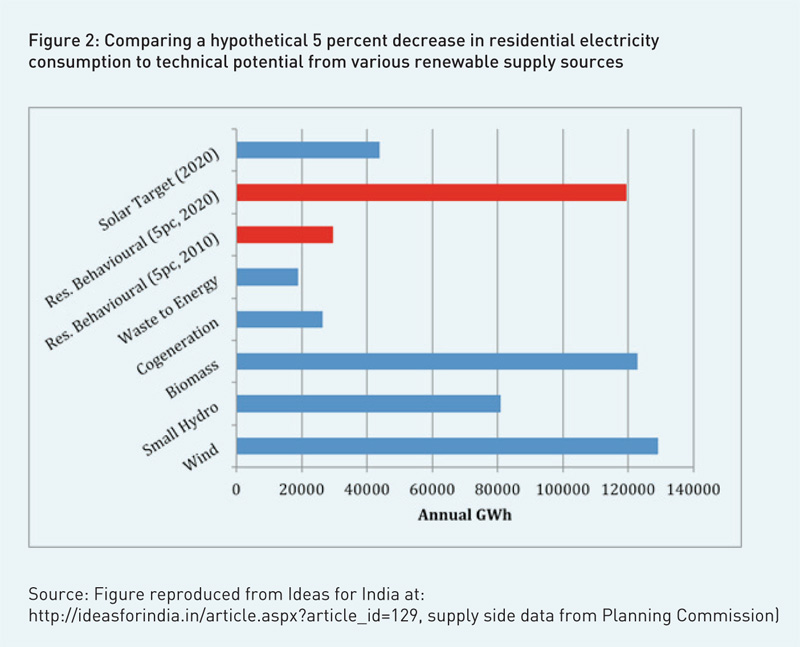

A good way to think about whether demand side policy is useful is to consider Figure 2. The graph simply compares the magnitude of a hypothetical 5 percent reduction in residential electricity consumption (a modest target achievable with small efficiency improvements) to Planning Commission estimates of the total technical potential available from various renewable sources. One thing seems clear – if it is worth thinking seriously about building renewable energy capacity today, then it is also worth thinking just as hard about demand side interventions and how to scale them.

The study also estimated the response of households to changes in electricity tariffs. This allowed for a comparison of the effectiveness of the behavioural nudge, relying on information alone, with changing prices for electricity. The results were compelling. Sustained over an entire summer season (May to August), households who were sent these report cards, reduced electricity consumption by over 8 percent on average.

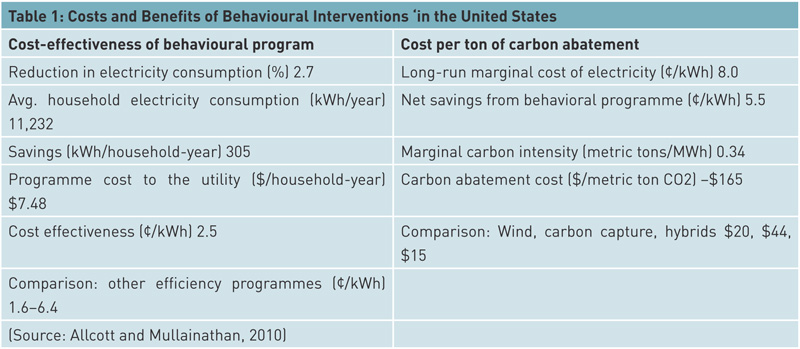

Potential savings aside, behavioural instruments might also prove to be low hanging fruit simply because they can be fairly inexpensive. Many ‘nudge’ type interventions rely largely on providing consumers carefully framed information. This type of intervention may be easier to scale up in many settings. Table 1 shows how the cost-effectiveness of peer comparisons compares to other alternative techniques of reducing carbon emissions or increasing efficiency.

Looking Beyond Financial Incentives

Changing public behaviour is a policy challenge in many areas. These include electricity consumption, public health and education. By far the most commonly suggested policy instruments involve those that appeal to financial incentives – either through changing prices or through conditional cash transfers.

Yet while the price incentive can be a powerful one, it is worth asking whether we could be more imaginative about how to change behaviour. For those of us worried about the environment and climate change in particular, behavioural methods – based around the use of carefully framed information – might provide the motivational thrust needed to reduce the energy we waste and redefine the energy we think we need.

Having said that, research on the effectiveness of behavioral techniques is still relatively young and much remains to be learned about when these ideas work well and when they do not. The answers to these questions can best be learned through a process of careful and repeated experimentation. Designing different types of ‘nudges’, testing them on pilot populations and scaling up the ideas that work should therefore be an integral part of how we design energy and environment policy.

FURTHER READING

Abadie, A and S Gay (2006). “The impact of presumed consent legislation on cadaveric organ donation: a cross-country study”. Journal of Health Economics. 25 (4): 599-620.

Allcott, H and M Greenstone (2013). “Is There an Energy Efficiency Gap?”. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 26(1): 3–28.

Allcott, H and S Mullainathan (2010). “Behavior and Energy Policy.” Science. 327(5970): 1204–1205.

Allcott, H and T Rogers (2014). “The Short-Run and Long-Run Effects of Behavioral Interventions: Experimental Evidence from Energy Conservation.” American Economic Review. Forthcoming.

Arimura, T, R Newell and K Palmer (2009). “Cost- Effectiveness of Electricity Energy Efficiency Programs.” Resources for the Future. Washington D.C.

Beshears, J, J Choi, D Laibson, B Madrian and K L Milkman (2011). “The Effect of Providing Peer Information on Retirement Savings Decisions.” Revise and resubmit at the Journal of Finance 2013.

Cialdini, R B (2007).“Descriptive Social Norms as Underappreciated Sources of Social Control.” Psychometrika, 72(2): 263–268.

Filipini, M and S Pachauri (2002) “Elasticities of Electricity Demand in Urban Indian Households” Center for Energy Policy and Economics Working Paper. (16).

Gillingham, K, R Newell and K Palmer (2006). “Energy Efficiency Policies: A Retrospective Examination.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 31(1): 161–192.

Handel, B R (2013). “Adverse Selection and Inertia in Health Insurance Markets: When Nudging Hurts.” American Economic Review. 103(7): 2643–2682.

Houde, S, A Todd, A Sudarshan, J A Flora and K C Armel (2013). “Real-time Feedback and Electricity Consumption: A Field Experiment Assessing the Potential for Savings and Persistence”. The Energy Journal. 34(1):87-102

Iyengar, S S, and M R Lepper (2000). “When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 79 (6): 995-1006.

Jaffe, A and R Stavins (1994). “The energy paradox and the diffusion of conservation technology.” Resource and Energy Economics. 16(2): 91–122.

Kahneman, D, J L Knetsch and R H Thaler (1991). “Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias.” Journal of Economic Perspectives. 5(1): 193-206.

McNeil, B J, S G Pauker, H C Sox and A Tversky (1982). “On the elicitation of preferences for alternative therapies”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 306.

Pichert, D, and K V Katsikopoulos (2008). “Green defaults: Information presentation and pro-environmental behaviour”. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 28(1): 63-73.

Reiss, P C and M W White (2005). “Household Electricity Demand Revisited.” Review of Economic Studies. 72: 853–883.

Schultz, W, J Nolan, R Cialdini, N Goldstein, and V Griskevicius (2007). “The Constructive, Destructive, and Re- constructive Power of Social Norms.” Psychological Science. 18: 429–434.

Singh, A (2006). “Power sector reform in India: current issues and prospects.” Energy Policy. 34: 2480–2490.

Sudarshan, A (2013). “Deconstructing the Rosenfeld curve: Making sense of Californias low electricity intensity.” Energy Economics. 39: 197– 207.

Sudarshan, A (2013). “The Behavioural Effects of Monetary Contracts: Using peer comparisons and financial incentives to reduce electricity demand in urban Indian households”. September 23-25, 2013. Stanford Institute for Theoretical Economics: Psychology and Economics Summer WorkshopTanjim, H and J A List (2012). “The Behavioralist Visits the Factory: Increasing Productivity Using Simple Framing Manipulations,” Management Science, INFORMS. 58(12): 2151-2167.

Tversky, A and D Kahneman (1981). “The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice”. Science. 211 (4481): 453-458.Wolak, F (2011). “Do Residential Customers Respond to Hourly Prices? Evidence from a Dynamic Pricing Experiment.” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings. 101(3): 83–87.